Desh Bandhu Gupta: The humble professor

The founder chairman of Lupin emerged as a beacon of hope for the Indian pharma industry, helping the sector find its place on the global map

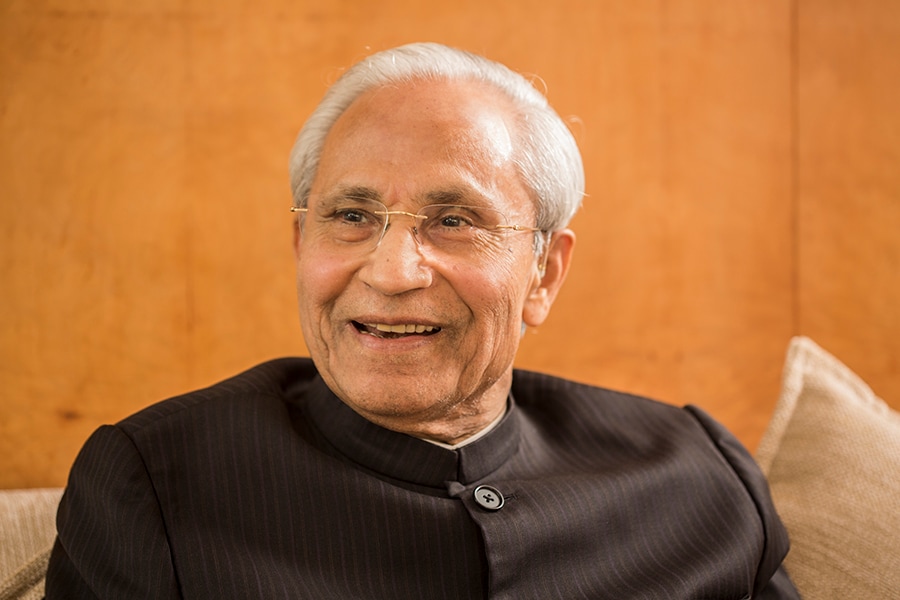

Desh Bandhu Gupta, founder, Lupin

Desh Bandhu Gupta, founder, Lupin

Image: Joshua Navalkar

“I have never looked at numbers. Numbers are just an outcome of the work done,” Desh Bandhu Gupta, the founder chairman of pharmaceutical company Lupin, had told Forbes India during an interaction in October 2016. The self-made billionaire passed away in Mumbai on June 26 at the age of 79.

Gupta’s professional life is a testament to what a hardworking, first generation entrepreneur can achieve, and benefit society in the process. The legacy that Gupta, fondly known as DBG, has left behind is the world’s fourth largest generics pharma company by market value and sixth largest in terms of sales, which earned $2.55 billion in revenue in FY17.

To think that Gupta, who was born in Rajgarh, Rajasthan, founded Lupin in 1968 with Rs 5,000 that he borrowed from his wife, shows the long and successful journey he traversed from being a professor of chemistry at the Birla Insitute of Technology and Science, Pilani, to becoming India’s 20th richest person with an estimated net worth of $5.1 billion (according to the 2016 Forbes India Rich List).

Gupta’s philosophy towards business is best exemplified by the rationale with which he named his company Lupin. The name draws reference from the Lupinus flower, which is known to nourish the soil in which it grows. With a disarming smile, humility and knowledge of chemistry (he holds an MSc degree in chemistry) as his biggest assets, Gupta founded Lupin as a manufacturer of vitamins, but the desire to serve a larger, social cause saw Lupin transition into manufacturing drugs to combat tuberculosis (TB), an infectious airborne disease that has claimed millions of lives in India over the years. Lupin persisted with the manufacture of anti-TB drugs for the domestic market despite the fact that it was a low-margin business, with drug prices largely controlled by the government.

In fact, Gupta was a contrarian in the sense that he believed that the prices of certain essential drugs needed to be controlled by the government, says Habil Khorakiwala, chairman of Wockhardt, who knew Gupta for four decades and called him a “competitor and a friend”.

In the late 80s and early 90s, Khorakiwala and Gupta were part of a committee formed to deliberate on drug policy, which comprised industry leaders such as themselves and bureaucrats. “We had a different perspective of the industry. His (Gupta’s) view was that some amount of price control was required, whereas my belief was that there is enough competition in the industry to let prices find their own level,” Khorakiwala recalls.

While the focus on manufacturing drugs that were of relevance to India continued on one hand, Lupin also expanded into new therapeutic areas, including complex generics and specialty drugs across cardiovascular, diabetology, asthma, paediatrics and gastrointestinal-related disorders, among others, and global regions like the US, Europe, Latin America and Japan.

DBG’s concern for social issues wasn’t restricted to making anti-TB drugs alone. Much before it became mandatory for Indian companies to spend a portion of their earnings towards corporate social responsibility measures, Gupta had pioneered the foundation of the Lupin Human Welfare and Research Foundation in 1988. Through the foundation, Lupin works across 3,463 villages across India for their economic, social and infrastructure development, impacting 2.8 million families.

It isn’t as if Gupta didn’t make mistakes and some of the calls he took didn’t work out as planned. But while it isn’t uncommon for entrepreneurs to err at times, it is the determination with which they bounce back that distinguishes them. In Lupin’s case, an unrelated diversification into real estate in the 1990s didn’t augur well for the company and left it saddled with a mountain of debt. The singular focus on India also meant that peers like Cipla and Ranbaxy made headway in the foreign markets.

To pare debt, Gupta sold a portion of his stake in Lupin to CVC International, a Citigroup company in 2003 and the new investors wanted a managing director to be brought from outside to bring the company back on track. While the induction of an external professional for the top job at Lupin may have been at the behest of investors, the freedom that Gupta granted to Kamal K Sharma to steer the ship saw the foundation of Lupin’s future growth, and a deep bond of friendship, being laid.

What followed was a twin process of balance sheet repair – aided by strict control on costs – and focus on research and development, which aided Lupin’s successful entry into developed markets like Japan and the US.

Sharma hung up his boots as Lupin’s MD after a decade in 2013, and made way for Gupta’s children – Vinita Gupta and Nilesh Gupta – to assume responsibilities as chief executive officer and MD respectively. He, however, continues as the company’s vice chairman and commands the same respect as Vinita and Nilesh.

While Vinita and Nilesh took the company on an aggressive and inorganic path of growth, Gupta and Sharma continued to be the sounding board for all major decisions, especially those related to mergers and acquisitions. “He (Gupta) ensured a great combination of professional leadership and entrepreneurial spirit and risk-taking ability in the organisation,” Khorakiwala said, and added that it was due to entrepreneurs like Gupta that the Indian pharmaceutical sector had become a globally competitive force to reckon with.

“With his passing away, India and the pharmaceutical industry has lost one of its tallest leaders,” Khorakiwala summed up.

First Published: Jun 27, 2017, 14:10

Subscribe Now