Cadbury's worms of graft: Whistleblower reveals all

As the Mondelez India (erstwhile Cadbury India) bribery investigation reaches its final lap, the man who blew the lid on the case tells Forbes India about the challenges he faced

Rajan Nair

Image: Joshua NavalkarRajan Nair remembers feeling a gnawing sense of foreboding in December 2010. He was at a Cadbury offsite at the Anantara Bophut Resort in Koh Samui, Thailand the team was there to unwind and take stock of the year gone by. Yet Nair found it hard to get the events of the last two months out of his mind.

The strapping six-footer vice president of security for all Cadbury units (in India, China and South Asia)—the job entailed looking at fraud, risk and security—had played a leading role in investigating a vast bribery scandal that had been uncovered in October 2010. Bribes had been paid to retrospectively secure permissions for a factory extension in Baddi, Himachal Pradesh, which had been hastily constructed in order to take advantage of tax concessions.

It wasn’t easy to probe colleagues in the know, or involved, but Nair with his take-no-prisoners approach had ploughed on with the investigation. If taken to its logical conclusion his work had the potential to destroy careers as well as entangle Cadbury in a regulatory mess with both Indian and US government authorities. No matter. “I am just doing my job and the company will support me,” is what he kept saying to himself at that time.

He’d received no follow-up emails after alerting his boss in Singapore, Adrian Wong, the director of security and special investigations at Kraft. (Note: Cadbury was taken over by Kraft in January 2010 through a hostile takeover. In October 2012, Kraft’s snack food division which includes Cadbury was renamed Mondelez International Inc.)

Wong had classified Nair’s investigation as a Special Situation Management One emergency—internal code for the company board being alerted. But Nair noticed that the top brass at Cadbury were doing their best to go slow on the investigation. Importantly, they had made no attempt to report it to the American regulator, Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC),

“I remember Rajan approaching me. He was visibly upset and said ‘they would come after me’,” former colleague Anita Singh Williams, who worked in Cadbury’s legal team, recalls when asked about the offsite. Singh Williams is currently the director-legal and compliance at Medtronic Pvt Ltd.

It was at the plenary session of the Koh Samui offsite that Nair’s fears were confirmed.

As a result of the investigation over November and December, at least three dozen employees were being questioned. Old records were pulled up, emails scrutinised and questions were being asked on decisions that, according to them, had been taken with the concurrence of the top management. Morale, company-wide, had hit an all-time low. As the offsite drew to a close it was down to Anand Kripalu, the then managing director, to motivate his employees. Kripalu, a persuasive speaker, made it clear that he’d go out of his way to protect the rank and file. “The company would stand by its employees,” he said in a bid to lift morale. But in his rallying call Kripalu also made clear his displeasure at the fact that the investigation was being pursed so vigorously. This unsettled Nair who, until then, believed he had Kripalu’s support.

Soon after, Nair pulled Kripalu aside and attempted to show him internal emails detailing bribe payments. Kripalu listened to him for barely a minute before setting off for the dinner pavilion. Nair walked to his room contemplating his next step.

That was the night Nair decided to turn whistleblower on what has turned out to be one of the largest bribery investigations by SEC to be faced by an American multinational in India.

Over the next month, Nair tipped off both the SEC and the Department of Justice (DOJ) in the US, and subsequently pursued the case with the Indian authorities—the Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) and the Directorate General of Central Excise Intelligence (DGCEI). He spent hours briefing government officials about the case as well as recorded testimony with the SEC and DOJ. The SEC and Mondelez reached a settlement in January 2017. Mondelez paid $13 million (Rs 89.5 crore) as fine without admitting or denying the charges relating to how the company maintained its internal accounting books. The DOJ investigation is still in progress.

Nair, 49, resigned from Mondelez in January 2013 but has continued to steadfastly pursue the case by following up with the investigations. Several former employees whom Forbes India contacted stated that they had been treated unfairly by the company. (Most declined to speak on the record as the company is paying their legal expenses and because Mondelez made them sign non-disclosure agreements.)

undefined Over the last three months, Nair has sat down with Forbes India multiple times detailing his journey, explaining his motivations for taking this public as well as making clear that his only agenda was and still is for the company to come clean[/bq] Over the last three months, Nair has sat down with Forbes India multiple times detailing his journey, explaining his motivations for taking this public as well as making clear that his only agenda was and still is for the company to come clean. This is the first time that Nair is going public about his role as whistleblower. “People lost their jobs for no fault of theirs, while the big bosses got away with just a light slap on the wrists. How is this fair?” he as well as the former employees who spoke on the condition of anonymity collectively ask.

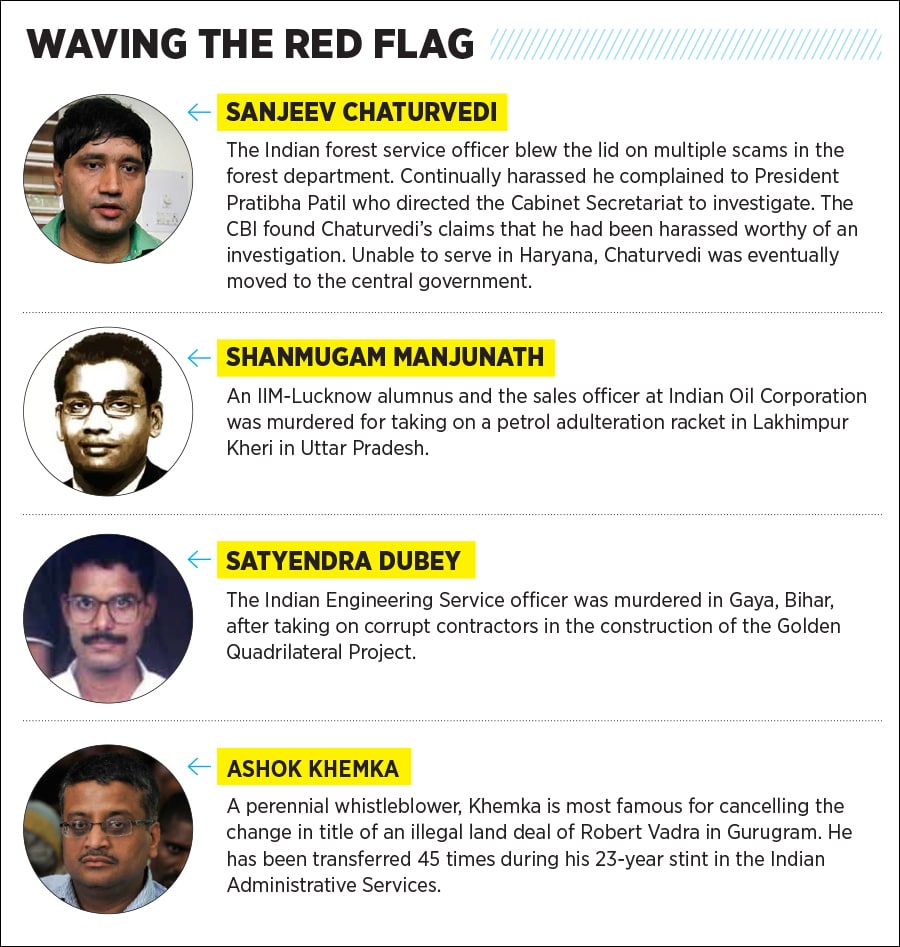

Nair is understandably under severe pressure. Consider how vulnerable whistleblowers in India are due to the lack of legal protection. The likes of Sanjeev Chaturvedi, Satyendra Dubey, S Manjunath and Ashok Khemka (see box) have faced considerable physical and mental harassment. “For the last six years I have lived in constant fear of my own physical safety and that of my family members,” says Nair. A law protecting whistleblowers continues to languish in the Indian parliament.

“The fact that there is no anonymity as far as the public sector is concerned and there are no laws for reporting fraud in the private sector [in India] speaks for itself. It is a sorry state of affairs,” says Dinesh Thakur in an email. Thakur had brought to light how pharma major Ranbaxy covered up unsafe manufacturing practices in its plants. In 2013, Ranbaxy pleaded guilty to several counts of criminal felony and agreed to pay $500 million to settle charges related to the manufacture and distribution of adulterated drugs at two facilities in India.

Mondelez declined to answer a set of detailed questions sent for this story. It also declined interview requests over the course of three months. In a statement the company said: “As a company, we have been responding to questions around these matters to the best of our ability considering that the matter is in the legal domain. It is therefore unfair of your publication to allege that the company was involved in any wrongdoing unless it is proven through the administrative and judicial process.”

The New Plant

By 2008, three years after Kripalu took the top job at Cadbury, the company was on a roll. That year sales were up 22 percent to Rs 1,588 crore while profits had risen 45 percent to Rs 389 crore. Rising incomes in cities as well as an employment guarantee scheme in rural India meant a large mass of Indians had entered the consuming class. Cadbury’s situation was hardly unique and subsidiaries of foreign consumer goods giants like Unilever and Nestle as well as homegrown Marico and Dabur showed rapidly rising sales and profits too.

It was around that time that Cadbury needed to expand capacity urgently while taking advantage of the tax incentives in the form of lower excise and income tax rates that several Indian state governments had announced—the incentives were available to those who set up before March 31, 2010. Cadbury’s existing factory at Baddi fit the bill perfectly. But the plan was to run into its first hurdle soon.

Shivanand Sanadi, Cadbury’s legal head at the time, cautioned that to get the tax exemptions for a new unit at an existing location Cadbury would need to show that it was completely separate from the existing unit. This would need new statutory approvals for everything, from the land and power connections to labour and raw material storage.

Sanadi advised the board members and senior management against this and was sidelined. “They disregarded my advice and chose to go with a legal opinion from an outside counsel, which eventually created a mess,” he says. He put in his papers in April 2010 and continued, at the request of Kraft management, to support the investigations in the matter eventually leaving the company in February 2011.

But with time running out, Cadbury quickly secured legal advice from noted tax lawyer Lakshmi Kumaran and went about setting up Unit II at Baddi. The new unit would manufacture, among others, Gems and 5 Star—two of Cadbury’s most popular products. Internal emails reviewed by Forbes India show Jaiboy Phillips, director— supply chain, stating that Unit II would result in £60 million (Rs 520 crore at the time) being added to profits over a period of 10 years.

RELATED:

Sticky situation at Cadbury India

Former Mondelez employees called in for questioning over 7-year-old case

With the business case being crystal clear, Cadbury’s Unit II at Baddi began production on July 30, 2009 the excise department was informed and the company believed it was on track to claim the incentives offered by the state of Himachal Pradesh. But they were taken aback by the excise department’s reply: Cadbury was asked to prove that the new unit was completely independent. Were the products being manufactured at Unit II or were they simply being repacked there? The excise authorities asked the company to show the manufacturing process through a flow chart.

Cadbury was unprepared to answer these questions—the company knew the unit had hitherto not been separate but over the years it has insisted that it had acted in “good faith” in claiming the excise benefit. However, internally it was doing everything it could to make changes to the plant after the letter was received from the excise authority.

An internal email written by Varun Ramanan, who then handled the finance function at Baddi, states that tax lawyer V Lakshmi Kumaran asked Cadbury not to file a reply and to “lie low instead”. Lakshmi Kumaran also, according to the same email, asked the company to “use its influence to revoke our earlier filing with the excise department to eliminate any record” and file a new letter.

During the course of its reporting, Forbes India received access to a variety of internal communication. A careful reading suggests that while junior employees were doing the ground level work, senior management, which included Kripalu, Rajesh Garg, director-finance, and Jaiboy Phillips, director-supply chain, were always kept informed of the steps taken.

Sample this: An internal email on February 8, 2010, talks about separating the employee register for Unit II. On July 15, 2009—a fortnight after the company wrote to the excise department—the first internal Management Development Committee meeting was held to approve the expenditure to be incurred for making Unit II separate. On July 22, 2010, Cadbury decommissioned its old SAP system and installed a new system so that back-dated invoices for the new unit could be issued. Also, it was only in 2010 that chocolates produced in Unit II had wrappers that explicitly mentioned their place of production as Unit II in Baddi. In its haste to set up a ‘separate’ unit, Cadbury had overlooked the fact that new wrappers were needed. A new letterhead for Unit II, used to send official communication, was also in use only from 2010. (Forbes India sent each of the above points as specific questions to Mondelez but received no response.)

While Cadbury worked to make changes internally, it found its hands tied by the government. As a foreign company, paying speed money for getting approvals was a strict no-no but permissions for a new factory had to be obtained. Adding to the confusion was Lakshmi Kumaran who had earlier said the company needed no new approvals for Unit II. He was to change his mind three times thereafter, and later, in a November 2009 meeting attended by Rajesh Garg and other employees, Lakshmi Kumaran asked the company to obtain new licences and, in case of litigation, he would represent them.

Cadbury knew it had to move fast. It had to obtain licences before March 31, 2010, to claim tax benefits and time was running out.

[qt]It is so complex, the level of detail and trickery is staggering. I’ve had to spend hours with government authorities like the CVC, the CBI and the DGCEI, and the US authorities to explain to them what was done and how it was done.[/qt] A confidential report titled Project Maxim, prepared by Ernst and Young (EY), lists the multiple bribes paid to government authorities through contractors engaged by Cadbury. EY lists a total of Rs 82 lakh paid to obtain factory approvals, separating the power line, pollution control board approvals and ‘under the table expenses’ to minimise sales tax penalty among others. Sanadi, the former legal head, says these approvals would have cost the company an application fee of about Rs 1 lakh to obtain legally.

Still, Cadbury continued to pursue what can at best be described as a dubious tax break. And all indications suggested it was on track to get away with it. After all it had successfully applied and received retrospective plant permissions even through the plants were not separate. On February 19, 2010, Garg wrote in an email to Kripalu that factory employees “are pushing to move some chocolate from Unit I to II via a pipeline to start trial runs of the new line, till Unit II making gets up and running… this is a cardinal sin per the whole concept… I want to bounce off the risk with you before I give them the green signal.”

The Unravelling

In September 2010, a disgruntled canteen contractor, Mohit Vesasi, contacted Nair and made a slew of allegations about the manner in which the Baddi factory functioned. Nair immediately sensed that this could get ugly and asked his boss Wong to fly in from Singapore to meet Vesasi in Chandigarh.

Nair, a veteran of several investigations—he had cracked several visa fraud cases for VFS Global, an agency to which embassies worldwide outsource their visa application collection, to a smuggling racket at Mumbai airport for courier company FedEx—spent the next month investigating Vesasi’s allegations and determined there was a prima facie case to be made for bribes paid. On October 3, 2010, Wong sent a Special Situations Management One note informing the board at Kraft. “I expected the company to come clean and report it to the US and Indian authorities. Instead they created smokescreens,” says Nair.

According to Nair, at a meeting held at January 26, 2011, at the Taj Lands End in Mumbai, EY detailed the bribes paid and made a presentation to the top management at Cadbury India. Yet, the top brass at Cadbury did nothing to notify the authorities. “They actively worked to close the investigation and to find scapegoats,” says Nair.

Unknown to them and also to Nair, Nair’s decision in Koh Samui in December 2010 to alert the US authorities was to have an impact in a few days. On February 1, 2011, the SEC issued a subpoena asking Kraft to explain payments in India that fell afoul of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

While it replied to the SEC saying that an investigation was taking place, Cadbury knew it had to act quickly and heads had to roll. An internal memo shows that four employees were fired, four received a written reprimand and one got an oral reprimand. Here the case of Garg, the CFO, is an interesting one. Several former employees who declined to be quoted due to their non-disclosure agreements have said that he had championed the setting up of Unit II in Baddi. Internal documents show that he was aware of the graft and did nothing to stop it. One internal email shows that Garg signed a cheque that could have been used as a bribe in November 2010 even after Anita Singh Williams from the legal team specifically told him not to do so. After Kripalu, Garg also stood the most to gain from a potential bonus payout.

On April 5, 2011, he was fired from Cadbury. And the next day, Kripalu, in an organisation-wide email, wrote that Garg would be moving on for personal reasons. This action seems to have riled employees. “You fire some junior level employees who barely make enough to survive and the person who orchestrated this gets away with a farewell email with no mention of the mess he created?” asks a former employee. Garg, who is now the chief financial officer of the Landmark Group, did not reply to emails seeking his comment.

Meanwhile the excise department started pursing Cadbury for unpaid taxes and went through a lengthy two-year investigation. Its Baddi factory was raided as well as its office in Mumbai. Employees spent the better part of two years answering showcause notices and Kripalu was summoned several times for questioning. In 2012, Kripalu was reassigned to manage Mondelez’s business only in India and its neighbours from being in charge of India and South-East Asia earlier. He left the company in May 2013. Kripalu is now the managing director of United Spirits and an independent director on the board of Marico.

In March 2015, the excise commissioner passed a scathing order against Cadbury. The company was fined Rs 342 crore in unpaid taxes and Rs 231 crore as penalty. The 154-page judgment states: “The investigations have proved as (sic) systematic and planned evasion with Anand Kripalu at the helm of affairs.” The order goes on to state, “I may add here that there is a difference between tax planning and tax evasion. The category of case falls under the category of planned tax evasion and has to be dealt with severely so that it serves as an example…” Cadbury has appealed against the order. The excise department has since sent another notice for unpaid taxes. If Cadbury loses, the total tax liability in India could approach Rs 2,000 crore—far higher than the planned savings that would accrue from Unit II. Kripalu and other officers of the company including Phillips and Garg were fined a total of Rs 2.15 crore.

The Road Ahead

As things stand, Mondelez is embroiled with multiple regulatory agencies. It has settled with the SEC and is appealing an excise order. It is also waiting to see if the DOJ initiates a criminal investigation. Sources told Forbes India that DOJ action is imminent. Justice department employees are said to have recently travelled to India to interview former Mondelez employees but Forbes India could not independently verify this.

While the case nears its final denouement in the US, Nair says he’s had his life upended. Like every whistleblower he lives with the anxiety of not knowing how the investigations by both the Indian and US authorities will proceed. He has no line of sight to their final outcome. Worse, he’s been unable to find a full-time job again.

Former employees too have had their lives overturned. They live under the constant pressure of being summoned to government agencies to record statements. In mid-April they were to appear before the Central Bureau of Investigation before the summons were rescinded. A few were worried about this harming their future career prospects.

Among the internal emails that Forbes India accessed was an exchange between Varun Ramanan who was in charge of finance at the Baddi facility, and his father in which the latter writes, “I heard that you are a little upset with practices that you are aware are not correct.” He prompts him to take up the matter with Garg and to handle it diplomatically. (The issue deals with how expenses were recorded in the SAP system.) This is one indication of the mixed feelings lower-rung employees had to live with while working in the company.

On his part, Nair has spent the better part of the last half decade working to educate government authorities on the case. “It is so complex, the level of detail and trickery is staggering. I’ve had to spend hours with government authorities like the CVC, the CBI and the DGCEI, and the US authorities to explain to them what was done and how it was done,” he says.

Nair is certain that the company did not act in good faith in claiming the tax benefits. He scoffs at the company’s assertion that it is an “honest and compliant organisation” and says it was just greed and a “culture” that made them believe they could get away with it—in fact, after the Kraft takeover, employees had to be trained to speak up if they noticed anything amiss with processes.

He also questions a regulatory system that emphasises on self-reporting when, at times, the corporate governance framework for companies is so weak and senior management incentive structures are designed to reward short-term benefits by cutting corners.

The pressure on increasing margins was escalating in the company, negatively impacting the approach to work and employees. One employee spoke about how Cadbury would rarely fire people in fact, the company worked with one advertising agency Ogilvy for over 30 years even though there had been instances of some advertising campaigns not resonating with consumers. “We never had this quarter-on-quarter approach earlier,” he says.

And then there is the victimisation faced by Nair. “Rajan was one of the brightest persons I know and I have no hesitation in saying he was victimised,” says Singh Williams. Nair had his reporting lines changed and was given a bad appraisal rating. He says he stayed on only to see that the investigation completed. But it was the manner in which the company treated his boss that finally made Nair put in his papers. On an official trip to Manila in January 2013 he remembers talking to a tense-sounding Wong who was regularly pressurised by his bosses to not take part in the investigation. When reached on the phone, Wong declined comment and said he wanted to put this chapter of his life behind him. Sanadi was also sidelined and not elevated to the Cadbury India board.

“The Indian operations wanted to keep this contained within India. Rajan took the step of bringing this to the knowledge of their Asian operations in Singapore. That was a sin they would never forgive him for. They saw him as disloyal to his colleagues in India,” says Christopher Brennan of Ziegler Ziegler and Associates LLP. Brennan is representing Nair in the US.As things stand none of the senior employees—Kripalu, Garg and Phillips—are with the company. Almost all junior employees who had a role to play in this episode have also left. And the company could be saddled with a bill that is several times the Rs 520 crore that would have accrued to its profitability over the course of 10 years.

Ironically, it is Adrian Cadbury, who was chairman of Cadbury and Cadbury Schweppes for 24 years, who wrote a pioneering report on corporate governance in 1992. Those associated with the company constantly ask, “How did a company that had the highest standards of corporate governance succumb to what can at best be described as a costly error of judgment and at worst be described as fraud?”

Mondelez declined to reply to specific questions sent by Forbes India. The company sent us a broad statement prior to publication of the story. The statement is reproduced in full below:

“As a company, we have been responding to questions around these matters to the best of our ability considering that the matter is in the legal domain. It is therefore unfair of your publication to allege that the company was involved in any wrongdoing unless it is proven through the administrative and judicial process.

Our appeal is pending before the CESTAT and is therefore sub-judice. It would not be appropriate for us to discuss legal arguments or factual matters under dispute during its pendency. We maintain that the decision to claim excise tax benefit is valid and we continue to contest the excise demand notices through the administrative and judicial process. We will continue to cooperate with all authorities in any enquiry connected with the issue.

With reference to your various questions on our former employees, as previously stated, we believe that our executives acted in good faith and within the law in the decision to claim excise benefit in respect of our plant in Baddi. As is standard industry practice in such matters, we will continue to support current or former employees who have asked for support.

The Company treats all employees fairly. Since the company is not aware of the identity of the alleged ‘whistle blower’ you refer to, there can be no question on treating him/her unfairly as is being inferred. It is unfortunate that some former employees continue to use certain sections of the media to rake up events which occurred so many years ago, for reasons best known to them.

We would also like to emphasize that people movements, including changes in reporting lines, are a natural part of any dynamic, fast-growing company, and ours is no exception. It is necessary to point out that this was post acquisition and as with any acquisition, people movements are natural. As a matter of policy and respect for individual privacy, we do not discuss the status or details of current or former employees.

To address your query on non-disclosure agreements, it is common industry practice to sign non-disclosure agreements with employees in sensitive matters or to protect the interests of the company.

It must be noted that the SEC investigation culminated with charges relating only to internal controls and books-and-records provisions of the FCPA. Mondelez International Inc. and Cadbury Limited reached an agreement with the SEC to settle these charges, without admitting or denying the charges.

And finally on our actions…since the acquisition of Cadbury in February 2010, the company began reviewing and adjusting, as needed, all operations in light of applicable standards as well as our global policies and practices. The next 12 to 18 months was spent integrating the businesses of Cadbury plc with Kraft Foods across the world, including in India. This integration focused on such high priority areas as Food Safety, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and antitrust. Mondelez India meets all applicable standards in these high priority areas.

We trust you will reproduce this note in full to represent the company’s perspective and to respond to the allegations being made by your publication at the apparent behest of questionable sources.”

First Published: Apr 26, 2017, 16:15

Subscribe Now