Baiting the Bull

Investors brace themselves as India's markets head towards bear territory

Illustration by: Chaitanya Dinesh SurpurAs Hindustan Unilever Ltd (HUL) prepared to report earnings on October 15 there was every expectation that India’s largest consumer goods company would present a stellar set. Nearly four years of low consumer price inflation had put more money in the hands of Indian consumers. The company had benefited from benign commodity prices and a cut in tax rates. Urban consumers had uptraded to more expensive varieties of toothpastes, soaps and detergents while their rural counterparts had entered the consuming class.

Illustration by: Chaitanya Dinesh SurpurAs Hindustan Unilever Ltd (HUL) prepared to report earnings on October 15 there was every expectation that India’s largest consumer goods company would present a stellar set. Nearly four years of low consumer price inflation had put more money in the hands of Indian consumers. The company had benefited from benign commodity prices and a cut in tax rates. Urban consumers had uptraded to more expensive varieties of toothpastes, soaps and detergents while their rural counterparts had entered the consuming class.

In many ways the market’s reaction to HUL’s results was an apt summary of its travails over the last six months. Increasingly, improved performance has not translated into higher multiples for future growth—a classic sign that signals the advent of a bear market. As investors become more cautious, it is important to remember that this comes at a time when on aggregate Indian companies are on track to post improved earnings over the next year. A 13 percent depreciation in the Indian rupee has not resulted in any repricing of the prospects of Indian exporters save for information technology companies. And spare a thought for those who’ve missed their earnings. They have been put in the doghouse with valuations cut by 40-60 percent.

“This is a market where we have both January 2008 as well as March 2009 valuations at the same time,” says Anup Maheshwari, joint CEO and CIO of IIFL Asset Management. “This level of divergence is rare.” According to him, out of roughly 5,000 companies listed, close to 20 percent are quoting at above three times book value and close to another 20 percent are at less than book value. While the mainline index has so far held on to its gains, traders and investors alike both say this feels like a bear market. For the record, the Sensex is up 2.8 percent so far in 2018 while the midcap index is down 20.5 percent in 2018.

Will the companies quoting at January 2008 valuations hold on or do they also start mean reverting to lower multiples? For now, there is a growing consensus that India’s four-year bull run is either over or set for a long pause. A host of factors—both global and local—have resulted in investors holding on to their cash or parking them in bank fixed deposits. Oil prices and interest rates in the US have moved up. Both are short-term negatives for India. The imposition of tariffs on Chinese exports will likely result in slower global growth. Add to that the uncertainty around next year’s election result and the outlook gets even more clouded. Aditya Narain, head of research (equities) at Edelweiss, believes that the market has been preoccupied with India’s deteriorating macroeconomic indicators and hasn’t even started pricing in what could be a tough election. There could be more pain ahead.

Bubble Territory

The seeds of India’s market troubles have been sown steadily over the last four years. As oil prices fell from $140 a barrel in 2013 to $30 in 2016 bond yields fell and money moved to the markets. Low bank deposit rates meant that retail investors returned to the market and systematic investment plans (or SIPs) brought in an average of ₹10,000 crore a month. (Total inflows were in the ₹16,000 crore a month ballpark due to lumpsum investments.) Low global interest rates meant that foreigners piled on to Indian and emerging market equities. They bought $26 billion (₹1.92 lakh crore) of Indian equities between 2014 and 2017.

This money came in despite low earnings growth. Stock valuations expanded relentlessly from September 2013 as Sensex price earnings multiples rose from 16 to 26 (see chart). On a historical basis valuations usually reverse from these levels and this time was to prove to be no different. What queered the pitch was the blowout rally that took place in late 2017 and January 2018 that caught a lot of investors by surprise and attracted a disproportionate amount of retail investors.

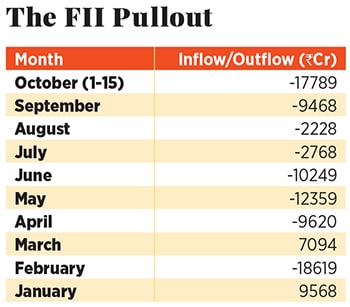

After the $8.97 billion (₹66,438 crore) pullout by FIIs so far in 2018 the Indian retail investor is now a wallflower. “Eventually the fall came due to a fairly predictable set of factors—the oil shock and the post-demonetisation normalisation of liquidity,” says Saurabh Mukherjea, founder of Marcellus Investment Managers. India’s bond yields are now at 8 percent, up 150 basis points in the last year and oil prices are up 21 percent to $80.5 a barrel. While Mukherjea says we are not in bear market territory yet, we should be thankful if the markets end the year at 30,000, which would be bear market territory. India’s four-year bull run is either over or set for a long pause Image: Kuni Takahashi/ Getty ImagesLastly, there is the ongoing normalisation of interest rates in the US. The Federal Reserve has indicated that it is on track for a 25 basis points rate hike this year to 2 percent and for three hikes in 2019. Higher yields and a depreciating Indian rupee have resulted in money flowing back to the US.

India’s four-year bull run is either over or set for a long pause Image: Kuni Takahashi/ Getty ImagesLastly, there is the ongoing normalisation of interest rates in the US. The Federal Reserve has indicated that it is on track for a 25 basis points rate hike this year to 2 percent and for three hikes in 2019. Higher yields and a depreciating Indian rupee have resulted in money flowing back to the US.

The NBFC Muddle

In the last month there has been an additional wrinkle in the funding of NBFCs that the markets have had to factor in. These shadow banks were making loans just like banks sans the deposit base or the regulation of the central bank. Money came from the short-term market and debt mutual funds. It was a classic example of borrowing short-term and lending long-term. As interest rates rose, lenders demanded higher yields to buy their commercial paper. In some cases the market froze.

On September 21, a mutual fund holding ₹300 crore of Dewan Housing Finance Ltd (DHFL) paper had to sell it at 11 percent, up at least 200 basis points from what it had been sold earlier. The market panicked and the DHFL stock slid 42 percent on that day. In September investors pulled out ₹211,000 crore from mutual funds that invest in treasury bills, certificates of deposit and commercial paper for shorter durations. It remains to be seen whether flows into systematic investment plans (SIPs) slow down in the months ahead.

What’s clear is that India’s NBFCs will be unable to maintain their 25-35 percent growth rates for personal, auto and home loans. (In a September 2018 cover story ‘Hook, Loan and Sinker’ Forbes India had questioned whether at 21 percent personal loans were rising too fast.) Rising interest rates would also mean that small and medium businesses would be unable to refinance their loans, possibly triggering defaults. Some expect these NBFCs to show a flat loan book this year. “It’s not as if the banks can’t offer these loans, but they are not half as nimble as these specialist financiers,” says Rajeev Thakkar, chief investment officer at PPFAS, a mutual fund. Already, companies have begun to price in tepid festive season sales as it is unclear if banks can pick up the slack. The recent festive season sales on Flipkart and Amazon were a washout for most fintech companies as they were unable to increase their lines of credit.

Investors Forbes India spoke to admitted that there was a lot of fear in the system. They are all using this opportunity to get out of stocks where there is even the slightest doubt about either the earnings growth or the business model. “We will have no more financing of loss-making food delivery startups by California pensioners,” one of them said by way of example of which businesses would bear the brunt. What’s clearly spooking them is the risk of contagion on account of rising defaults.

A large infrastructure conglomerate IL&FS has been unable to pay its short-term debt. The government fired the board and tasked a new board with a plan to get IL&FS back on track. Supertech, a reputed builder in the National Capital Region, has also defaulted on its debt payments. In the months ahead investors say that developer defaults could rise. “There’s anxiety and a lot of nail-biting as no one knows how, when and where from the next default will come from. Sell first, think later is what people are saying,” said a seasoned market veteran. He declined to be quoted by name.The jury is still out on whether the lack of credit would have a material impact on growth. Some, like Mukherjea, estimate a 1 percent cut to GDP estimates. Others, like Thakkar, say it is difficult to isolate one factor for an increase or decrease in GDP. But this much is certain—the cyclical pickup that many were anticipating is unlikely to come. “There had been expectations of a cyclical recovery. What is required is a certain amount of risk appetite and visibility of upside, which is possible when markets are high and capital accessible,” says Narain of Edelweiss. “At the margins there is some growth that won’t come through.” Edelweiss has not revised its full year forecast upwards and is sticking to 7.3 percent even after an 8.2 percent Q1 number.

Leading Up to May 2019

Investors have so far been taking it step-by-step. They first contended with rising oil prices, then rising bond yields, then a depreciating rupee and then a freeze in financing for NBFCs. Each of these four has left a deeper and deeper scar. Each time the market has bounced back they’ve rushed to sell. Even companies in sectors that have benefited from proactive government policies have sold off. Take road builders. The last infrastructure push saw road builders go belly up as they took the risk of collecting toll and bid aggressively. The government negated this this time by paying them upfront for work done. Even here, stocks are down 35-55 percent with no change in business fundamentals.

In the run-up to next year’s election, market prospects will be determined in two phases. The state elections in December in Rajasthan, Mizoram, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Telangana will provide a roadmap for the national polls in May 2019. National alliances, if any, will be stitched up post these polls. If the market believes that the present government is unlikely to come back, the sell-off could be brutal and swift with the main worry centering on uncontrolled spending by a coalition government. On the other hand, no one expects a market rally if the present government returns.

“Be prepared for pain in the near term,” says Thakkar of PPFAS. At 27 percent the fund has one of the highest levels of cash in its history and is waiting for an opportune chance to deploy. They only plan to invest in businesses with a five-year horizon and are willing to wait it out till they find the right opportunity. That’s prudent. In these uncertain times it pays to wait.

(Images by: Mexy Xavier)

First Published: Oct 23, 2018, 10:59

Subscribe Now