Measure for Measure: When Quantitative Meets Qualitative

Leadership, collaboration and trust are soft measures that translate into 'hard' results

The phrase “What gets measured gets managed” has been attributed, in various forms, to Tom Peters, Peter Drucker, and even Lord Kelvin. While the phrase’s origin may be murky, the underlying idea has tremendous power for leaders. Without measures, leaders and their organizations face a nearly impossible task in coordinating efforts or assessing progress. So, the question we face is not whether to measure, but rather what to measure and how to measure.

Most current measurement approaches are far too narrow to provide useful guidance. Relentless pressure from shareholders and analysts has contributed to a management fixation on near-term financial performance. Unfortunately, this is just one output measure, and not a particularly useful or actionable indicator, because it’s a ‘trailing indicator’—a measure of what happened that doesn’t always help you understand how to affect the outcome. Even when businesses focus on share price, the measure is the stock market’s projection of future financial returns, which rarely incorporates a detailed understanding of the organization’s ability to sustain those returns.

The Balanced Scorecard approach developed by Kaplan and Norton encouraged managers to consider operational and organizational dimensions beyond the purely financial. Their subsequent work on strategy maps pushed for a relational understanding of how the interactions among the chosen measures reflected elements of the value creation system in a business. As much as their work was a profound step forward, it still clung to a quantitative bias that limits the view we get of the business and our ability to affect outcomes and change.

What we need to do is to move beyond a multi-faceted approach to measurement and take an integrative approach—one that balances multiple dimensions of the business, includes both input and output measures, and most importantly, values qualitative information on a par with quantitative data.

Qualitative measures can include a wide range of information, such as customer comments, focus group findings, performance review narratives, open responses on employee surveys, or after-action review summaries. Three attributes make such information a ‘measure’:

It must be relevant. Performance changes in the measure must be linked to business outcomes that matter. This attribute is sometimes called ‘validity’, and the linkage can be self-evident or statistical. For qualitative measures, statistical linkages can be more challenging to demonstrate unless you use scales such as a five-point Likert to capture a qualitative assessment. Self-evident relevance, or ‘face validity’, comes from the logical or intuitive connection of the measure to a desired result.

It must be replicable. Useful measures rely on data gathering methods that are sustainable over time and are worth the effort. If collecting the information requires adding a large infrastructure and increasing workloads across the organization, the value of the measurement will need to justify the investment.

It must be reliable. Changes in the measure need to be strongly linked to changes in outcomes. If the measure is directly of an outcome, the linkage is simple if the measure is of an input that contributes to the outcome, the linkage can be logical or a correlation. Thanks to undergraduate statistics courses, we can expect choruses of, “correlation does not mean causation.” This is true, of course, so the logic of the linkage becomes very important and a simple cause-effect relationship may be less likely than a causal loop systems relationship.

In research conducted over the past five years, our firm [Interaction Associates] has tracked a strong and persistent relationship between leadership, collaborative operational practices and financial results. Comparing companies that were able to grow their profits by more than five per cent last year with those that could not, we found that the high profit growth companies out-performed the lower profit growth companies across every survey question that assessed three things: leadership, collaboration, and trust behaviours. In short, these ‘soft’ measures translate into ‘hard’ results.

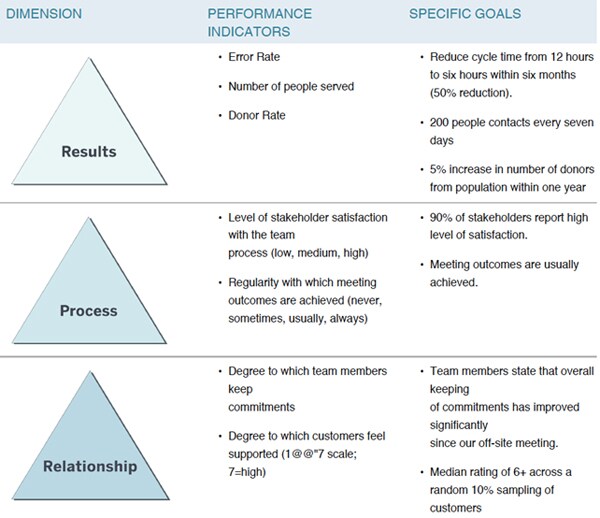

Leadership, collaboration, and trust behaviours are all examples of sustaining actions, and they all have the potential to contribute to business results. But, determining appropriate measures of such things can be a challenge when the areas being assessed are not financial. One relatively simple framework for measurement is to consider the Results, Process, and Relationship dimensions. Figure One provides examples of measures in each area.

So, how do we get started? Most business measurement efforts start with the financial or operational results the business has set out to achieve. But, that focus is too narrow. An integrative approach looks across all three dimensions—Results, Process and Relationship—and has five steps.

Step 1: Envision the Desired Future State. The organization should start with a vision of the desired future state for each dimension, taking into account that they should all be aligned and mutually reinforcing. For instance, an aspiration for a collaborative and highly involved relationship climate would be out of alignment with a set of process goals that were dictated without any input from those who would be charged with achieving them. Ideally, this ‘visioning exercise’ can provide an opportunity to engage people across the organization and at many levels in a collaborative experience. Some organizations take a diagonal slice of high-potential employees and task them with developing an initial draft of this vision, which they subsequently socialize across the organization.

Steps 2: Identify Measures. Having established a multi-dimensional vision of your future, identify both quantitative and qualitative measures for each dimension. The quantitative measures will provide trackable and trendable metrics, while the qualitative measures will provide a nuanced assessment of inter-relationships, causal factors, and emerging issues. The mix of quantitative and qualitative measures will help to create a ‘dashboard’ that is meaningful to more people in the organization: some people are naturally drawn to quantitative and logical data and will want to see how the company is performing against ‘the numbers’ while others will be concerned about whether the organization is performing in alignment with its values, operating norms, and goals, and will seek out more qualitative information.

Steps 3: Define Replicability. Relevant and reliable measures are useless if there’s no way to efficiently capture the information. Replicability is the sticking point for many measures efforts: while metrics may seem to be a ‘science’, there is an ‘art’ to deciding what to measure. Often, replicability depends on being careful not to be drawn to what is most easily measured, but not necessarily reliable and relevant. Instead, measure factors that will move in tandem with the outcome you want. For instance, most organizations want to balance their cost of acquiring new business with the profitability of that business. It would be difficult to get a real-time measure of the word-of-mouth activity inside a customer’s business, but surveying customers about their likelihood to recommend your business to others and tracking the Net Promoter Score can quickly provide a sense of the businesses standing in the eyes of customers. Augment that with qualitative questions on the survey or focus group conversations and a richly coloured picture begins to emerge.

Step 4: Identify Intermediate Goals. Work backward from the future state to identify intermediate goals for both the quantitative and qualitative measures. Depending on the timeframe chosen for the future vision, it may be perceived in the organization as compelling and attractive, but unattainable. Creating a set of nearer term goals against which the organization can measure progress provides the opportunity to create momentum and enthusiasm for the journey.

Step 5: Make it Habitual. Having done all this good work in creating an integrated system, keep in mind that your journey has just begun. Consistency in attention is the key, because people aren’t motivated by measures they don’t see. Leaders need to incorporate the measures into their ongoing communication. For example, when Motorola embarked on its journey to improve quality, every meeting started with an update on quality and at Dupont, meetings start with safety updates. Consistent leadership attention and visible support for the importance of the factors being measured is a non-negotiable.

By taking the integrative approach to measurement described herein, leaders can broaden intention and involvement in pursuing business goals across the organization.

Andrew Atkins is the Chief Innovation Officer at Interaction Associations, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Kevin Cuthbert is

First Published: Sep 24, 2014, 06:26

Subscribe Now