How solution economy can solve bigger economic problems

Paul MacMillian, head of Deloitte's Global Public Sector practice talks about the collaborative economic system that is emerging to create value around the world

As per the title of your book, you believe that we are in the midst of a ‘solution revolution’. Describe what you see happening.

It has become clear to most people that we can’t rely on government alone to tackle wicked problems such as climate change, poverty and crumbling infrastructure. My Deloitte co-author William Eggers and I set out to explore the growing space that exists between government performance and citizen expectations, and how society is working to close the gap. We found that there is a new, more collaborative economic system emerging that has a distinct ‘solution orientation’ around solving big problems. We call it the Solution Economy, and the players include business, government, philanthropy, and social enterprise. The grass-roots citizen- powered movement plays a key role, as well. Everyday citizens now have the ability—through the Internet and social media—to get involved and take on big problems.

The way the Solution Economy players approach problems is very different from the way governments have historically operated. In particular, the people involved fully expect to be able to make an impact in a reasonable period of time. By erasing private-public sector boundaries, the ‘Solution Economy’ is unlocking trillions of dollars in value.

Organizations that mix profit making with a social mission fall into two categories: social enterprises and market innovators. Please describe the difference between the two.

Social enterprises address a community or social need through a business. The goal is for the business to eventually be self-sustaining, but in the early days, trade-offs are usually accepted with respect to financial return. That is not to say that an altruistic agenda precludes sound business savvy. Seattle’s FareStart is a good example: this catering company and restaurant is staffed by cooks hired through a job placement program. It has flourished, supporting the delivery of more than five million meals to the disadvantaged. They also launched a café to train young baristas, combating the city’s high rates of youth unemployment and homelessness.

Market innovators, on the other hand, specifically set out to address unmet consumer needs, filling a gap in a previously-untapped market. A prime example here is Unilever, which has been introducing its products into markets at the bottom of the pyramid in recent years. It started Project Shakti as part of its efforts to introduce Lifebuoy soap in India. This initiative is focused on enabling entrepreneurship in rural India and increasing awareness of the importance of hand-washing, with an end goal of reducing infant mortality.

Increasingly, the distinction between social enterprises and market innovators is going to be harder to make. The lines are often blurred, as in the example of Project Shakti, which is a market-innovation approach embedded with social benefits. Another example is what Safaricom—one of the leading integrated communications companies in Africa—is doing in Kenya. A huge percentage of Kenyans didn’t have access to banking in any form, so Safaricom filled a need while also having a tremendous social impact: with their M-Pesa mobile banking phone app, people can now conduct business and receive entitlement payments, amongst other things. Thanks to this initiative, over 17 million subscribers now have access to financial services. Safaricom extended its basic service offering to serve an unmet need, and while they didn’t set out to be a social enterprise per se, this initiative is providing significant social benefits to its users.

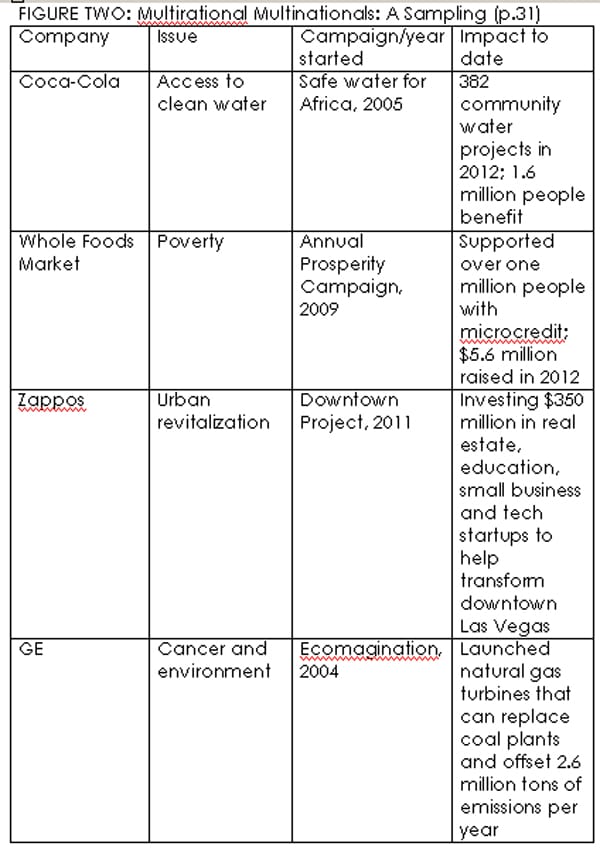

You call these companies ‘multirational multinationals’. What does it take to become one?

The distinguishing feature, as in the case of Unilever and Safaricom, is the idea of embedding social good into your business strategy. These companies take corporate social responsibility several steps beyond philanthropy in an effort to really understand their footprint in a community, in a country, and on a global basis, and how that can be addressed as part of their business strategy.

These organizations operate on the understanding that caring solely about profits is no longer rational in this new economy and that in the long run, this is actually a liability. Multirational multinationals embrace this idea and understand that relegating socially-minded activities to the sidelines ignores the tremendous (positive and negative) impacts that a company’s mainline operations can have.

For instance, if you’re going to sell hydroelectric power in an emerging market, how could community-based groups come into the picture? Are you leveraging different forms of capital, whether through not-for-profit or international development networks? What is your partnership model? Increasingly, we are seeing corporations partner with civil society organizations, other businesses or international donors. Increasingly investors and shareholders are starting to look for these things as part of a company’s business sustainability.

What does it take for these types of models to achieve scale?

When larger societal issues are seen not as ‘charity cases’ but as actual market opportunities, the actions taken are automatically more scalable and viable over the long term. Many of these organizations are creatively applying or re-combining technologies, and in doing so, they are eliminating trade-offs and producing dramatically better results for a lower cost. As such, they tend to be ‘built for scale’, with the potential to reach thousands—if not millions.

Kiva.org is a great example. It’s a platform set up by a couple of Americans where everyday citizens provide loans to social entrepreneurs and small businesses around the world. In just half a decade, it has raised half a billion dollars for a million entrepreneurs in more than 70 countries. In this case, scale is fueled through conscious consumers and everyday citizens who are interested in doing good.

Of course, the goal isn’t always to keep getting bigger and bigger. The Acumen Fund is a New York-based fund that looks for early-to-mid stage sustainable businesses in emerging markets and asks for a $250,000 to $3,000,000 capital investment up front. They get these companies started up, and then at a certain point they say, “Okay, this business is on its way we are not going to be involved in the next level of financing.” At this point, others get involved. In the case of Husk Power Systems in India, Acumen provided an initial investment before the Royal Dutch Shell Foundation and other cross-sector organizations came on board. A key element of Acumen’s model is ‘patient capital’. A return on investment is still the ultimate goal, but they are prepared to take a bit longer than usual to see it.

Of course, the goal isn’t always to keep getting bigger and bigger. The Acumen Fund is a New York-based fund that looks for early-to-mid stage sustainable businesses in emerging markets and asks for a $250,000 to $3,000,000 capital investment up front. They get these companies started up, and then at a certain point they say, “Okay, this business is on its way we are not going to be involved in the next level of financing.” At this point, others get involved. In the case of Husk Power Systems in India, Acumen provided an initial investment before the Royal Dutch Shell Foundation and other cross-sector organizations came on board. A key element of Acumen’s model is ‘patient capital’. A return on investment is still the ultimate goal, but they are prepared to take a bit longer than usual to see it.

What can governments do to facilitate the Solution Economy?

Plenty! In the Western industrial world, government is the biggest player around, overseeing everything from education to health care to social assistance and housing. In these industries they are the market, in some respects, so the way they procure is very important. Whether that means having ‘community development value creation’ as part of their procurement plan or changing the way they procure because they’re trying to attract innovators into the market, they have a significant role to play.

Government also has a role to play in the legislative and regulatory space, because the tax treatment of social enterprises, for example, is key to how they grow. Governments can also encourage citizens to contribute towards solving societal problems through open data platforms, contests and challenges. As we show in the book, these days, all sorts of things can be done to encourage citizen participation, with some pretty impressive results.

Last but not least, governments also have something to offer in the realm of measurement and reporting. They are sitting on heaps and heaps of Big Data on key issues such as school performance transportation rates, wait times at hospitals and much, much more. Through partnerships with other players in this space, they can bring key insights to outcome measurement and the effectiveness of solutions being put forward to address societal challenges.

One type of ‘wavemaker’—your term for the people spearheading the Solution Economy—are conveners such as TED, Davos and the Clinton Global Initiative. Some critics label them as ‘gabfests for the elite’. What is your take on them?

I can see where that comes from, but I think it’s unwarranted. Through the Clinton Initiative alone, $88 billion has already been pledged towards global solutions to some of the most challenging issues we face. It’s difficult to imagine that not having an impact. If you think about the convening power of Davos alone, it brings together some pretty significant global leaders who wouldn’t otherwise come face to face. I actually think there’s a lot to be said for this type of international collaboration. The World Economic Forum’s Global Shapers Community is another great example of how some of these conveners are bringing wavemakers (in this case youth) together, in an effort to promote innovation within the next generation of leaders.

I think some of the smaller players should start to emulate these models, because getting business, government and civil society together around the table to discuss big problems is very important. It doesn’t have to be done at a global level: it can be done on a regional, city or community level, as well.

Paul Macmillan is the Global Industry Leader for the Public Sector practice at Deloitte. He is the co-author of The Solution Revolution: How Business, government and Social Enterprises are Teaming Up to Solve Society’s Toughest Problems (Harvard Business Review Press, 2013).

Reprinted, with permission, from Rotman Management, the magazine of the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management. www.rotmanmagazine.ca

The Solution Economy is Powered by Six Features

While each is powerful in its own right, real breakthroughs come from weaving them together.

Wavemakers: a new set of non-governmental contributors is bringing unprecedented resources, versatility and creativity to societal needs. They include investors, conveners (TED, Davos), citizen changemakers and multirational multinationals.

Disruptive technologies: technologies like mobile, social (online communities), analytics (data mining) and cloud computing enable the mobilization of massive resources around big challenges.

Impact currencies: value creation and exchange are taking place in new ways. Currencies in use include credits, data, citizen capital, reputation and social impact. Examples: carbon credits trade in a $176 billion market and globally, people provide more than $1.3 trillion in volunteer services.

Public value exchanges: the impact currencies of the solution economy are being traded across a variety of novel exchanges, including crowdfunding platforms and two-sided markets, which link buyers and sellers directly, with one side of the market subsidizing the other. Examples: Kiva, one of the world’s largest microlenders and Mission Markets, a new stock exchange that offers shares worth more than $336 million.

Solution ecosystems: silo-free ecosystems connect wavemakers with a single core issue at their centre. These include innovation ecosystems base-of-the-pyramid ecosystems and life-saving ecosystems. Example: Tata Group’s $700 house.

First Published: Mar 25, 2015, 06:44

Subscribe Now