Ambiguous Problems Demand Guiding Rules, Not Rigid Plans

Ambiguous problems are not just academic exercises; they are existential threats in that they can threaten the very survival of an organization

In the movie The Chess Players, two noblemen in 1850s India obsess over a long game of chess, while their kingdom slips into the hands of the British East India Company. When they finally wake up to the new political reality around them, they grumble: “The Indians invented the game, but the British have changed the rules!”

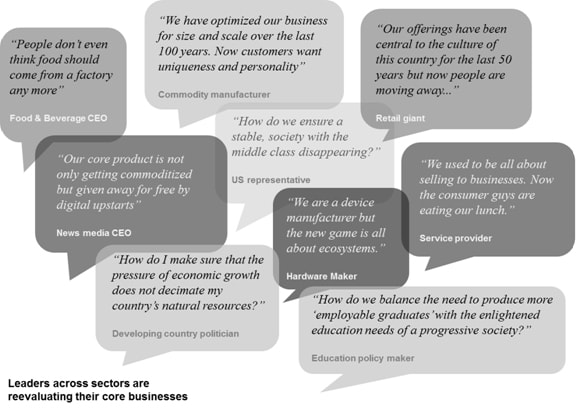

The noblemen’s perception is similar to today’s leaders’ when faced with unforeseen disruptions to their core business.

In reality, it’s not that the rules have changed it’s that an altogether different game is underway. Many leaders are finding that their plans for the future look great within the neat boxes of Powerpoint and Excel, but are often toothless in the face of unpredictable forces in the real world outside.

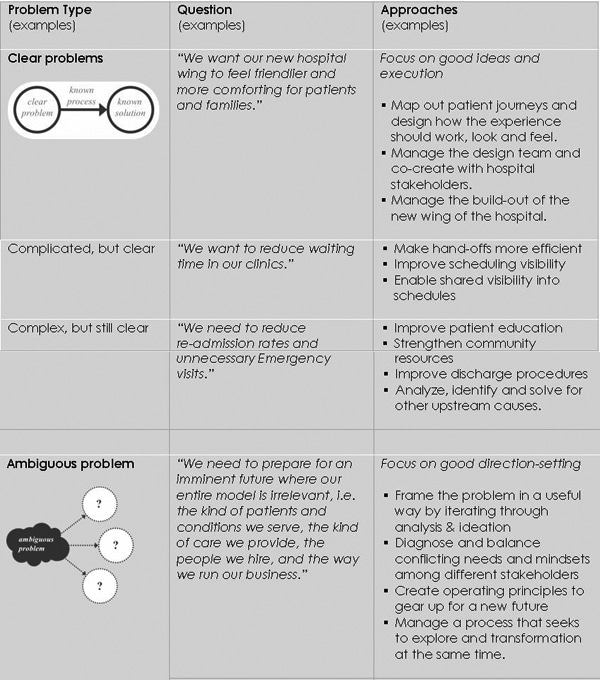

The problem is, the games we think we’re playing involve traditional strategic problems that are clearly defined – the kind we’ve studied since our days in school. Like chess, they have fixed constraints, known moves and finite boundaries. However, the problems we face today are much more unclear and ill-defined. To visualize what these ambiguous problems look like, imagine a game of chess where the rules and the game board itself can be changed by players at every turn as a result, you don’t know who you are fighting against or how to win the game. Ambiguous problems are not just academic exercises they are existential threats in that they can threaten the very survival of an organization (see Figure One.)The problem with traditional approaches to strategy is that they were developed in response to clearer problems and more predictable market conditions. This approach works great when data extrapolated from the past also helps to explain the future. In such situations, the mark of a great manager is the effective orchestration of people, time and resources. In the case of ambiguous problems, however, these skills are considerably less relevant. That’s because most large corporations today have the ability to create similar ‘things’ and manage projects of equivalent complexity where they stumble is in figuring out which direction they should follow when their goals are less clear.

Take the case of cellphone manufacturers in the years since 2000. There is no technical reason why Microsoft, RIM, Nokia or Motorola could not do what Apple did. These companies were drawing from similar and overlapping pools of technology, talent and resources. Instead, at each strategic fork in the road, they made seemingly rational choices that actually left them more vulnerable to disruption. For example, RIM and Nokia’s focus on their core markets – i.e. business customers and emerging markets, respectively – prevented them from innovating at the higher-end consumer side of the market. The net result was stagnation.

What these companies lacked was a clear understanding of where to point their organizational machinery in order to win, and a clear guide to help their leaders make those decisions.

I’m not talking about missions, visions or ‘product roadmaps’ – they all had those. But Apple, of course, had something special in Steve Jobs: a creative compass and a ruthless editor who laid down tough rules to help them decide where they should go and where they shouldn’t.

While other organizations may not be able to clone a guide like Mr. Jobs, they badly need the kind of guidance he provided.

To achieve this, leaders must create a clear set of guiding rules to help navigate an uncertain future. Organizations that have endured through tough times have always relied on such rules, even if they were unspoken. For some examples, see Figure Two.Such guiding rules help an organization tackle ambiguous problems in ways that other tools cannot. To understand why, let’s look more closely at the difference in the nature of problems:

Today’s ambiguous problems are fundamentally different from the ones we have been taught to solve because they involve situations where both ‘ends’ and ‘means’ – where to go and how to get there – are unclear. In addition, the exact nature of the problem itself is in question. While our problems have become more ‘wicked’, we continue to attack them with tools designed to solve clear problems. Like our deluded chess players, we are playing the game that we know how to play, not the one that’s actually afoot.

The problem with traditional tools – like strategic planning and innovation – is that they are either too restrictive or too divergent. To illustrate this tension with a metaphor, think of two different situations where you might have to navigate a city. One extreme is a hectic business trip, where you know exactly where to go and want to get there fast. On the other extreme is a leisure trip where you’d like to experience the city in a unique, personal way. A traditional strategic plan is like a GPS with turn-by-turn instructions – it seeks to minimize risk and to get you to from Point A to Point B efficiently. In contrast, innovation is more like a travel guidebook – it expands the options available to you, and helps you find places you wouldn’t have known about otherwise.

Ambiguous or ‘wicked’ problems, however, are very different. It’s as if you’ve woken up in an unfamiliar city with no idea how you got there, and without a clue about what to do. Each of our traditional approaches, in isolation, is inadequate in this scenario. On one hand, it is an opportunity to explore and discover hidden possibilities but you also need to hone in on an actionable strategy that can improve your situation.

To survive and thrive in such situations, prescriptive plans are the wrong tool – we need to focus instead on guiding rules.

Guiding rules have wisdom encapsulated in principles that allow us to explore while keeping us safe and on track, and they help with the direction-setting capability that is sorely lacking in many of today’s organizations.

It’s worth looking at the effect of guiding rules on a few familiar organizations. Walmart, for example, became a retail giant largely by strict adherence to its most tightly held rule: their lowest price guarantee. But when the company strayed from that path and attempted to introduce higher-end fashion labels, customers were turned off. By contrast, the Target retail chain has thrived by following their own guiding rule: deliver great design to the masses. Similarly, imagine if Kodak had an internal rule that said “Always seek to push the boundaries of photography.” They might have been less tied their core technology, and in quite a different market position today.

Consider the Mayo Clinic. Its “patient first” mantra is core to its unique value, and has served the institution well as a guiding rule, setting Mayo apart from many other healthcare institutions, where the unspoken mindset is “Doctors first!” Mayo’s guiding rule actively helps solve problems it is famous for its physician ‘huddles’ where specialists cut across departmental silos to solve a patient’s case together. It has also told generations of Mayo leaders what not to do, i.e. compromise on their ‘integrated practice model’, rather than follow the more common model of independent specialists. Rules like this help organizations carve out unique value while doing what’s best for their customers.

How can you go about creating such guiding rules for your organization? There are three critical steps: Diagnose, Design and Communicate.

Step 1: Diagnose the underlying cultural drivers of surface problems. Problems are caused by people, not just processes, so the more ambiguous the problem, the more important it is to dive below the surface of conventional wisdom. Our surface behaviours – the building blocks of our culture – are like the tip of an iceberg that hides our attitudes, mindsets and values. Until we diagnose the underlying drivers, we are not likely to get at significant, lasting change – within our organizations or in the outside world.

Ways to unearth hidden issues can be drawn from many fields: engineers use ‘root cause analysis’ to detect structural problems like hairline cracks in bridges anthropologists use the ‘thick description’ – to understand cultural norms sociologists and psychologists analyze the stories people tell, reading between the lines to reveal the implicit mindsets that drive people’s actions and behavioural economists look for built-in biases and ‘algorithms’ in our decisions.

An example of such a cultural rule is, ‘Doctor knows best’. This rule may be unspoken, but it is widely shared and deeply ingrained in healthcare, and it may in turn drive counter-productive mindsets. For example, the belief that “Pointing out a problem amounts to questioning a physician’s expertise.” In the world of hospitals, such underlying factors prevent some physicians from consulting or alerting other physicians, consciously or unconsciously. We find nurses who are too scared to bring up what might be a ‘small issue’ with physicians. We also find families that have too little self-belief to trust their own instincts in such situations, even though they may be the only ones who can connect the dots. But at the Mayo Clinic, the “patient first” rule helps to combat this fear of questioning individual physicians, for the greater good of the patient.

Great leaders have always understood that to cause significant change, you have to first understand what drives the people you are trying to change. Gandhi knew and leveraged this. He succeeded by starting with unique insights into the mindsets of both ‘rulers’ and ‘subjects’. Unlike many of his contemporary freedom fighters, he saw the British system’s need to be seen as civilized, equitable and fair, and as a result, chose the diplomatic path rather than declaring outright war. At the same time, he went on a journey of re-discovery into the Indian heartland, and observed the potential for quiet sacrifice that ran through the culture of its masses. His unique model of change-making is still being applied by activists in 2011 to fight big ambiguous problems like corruption in society.

Step 2. Use design as a way to reframe the problem space.

Most people think of design as a way to come up with solutions to problems. But as we have seen with culture, solving isolated surface issues may not solve the underlying systemic issues. For example, research into front-line problem-solving behaviours shows that nurses in hospitals show a lot of creativity in solving problems that occur on hospital floors all the time, but that effort does not add up to systemic learning or solving root problems.

Ideation (and design in general) should actually serve to expand or reframe the problem space. When we start out with an ambiguous problem, the boundaries of the problem are, by definition, unclear. One could meticulously follow a very rigorous process, and end up solving the wrong problem – and unfortunately, this happens all the time in the corporate world.

An example of using design to reframe a problem comes from the city of Bogota, Colombia, which was one of the most crime-ridden cities in the world in the 1990s. Then-mayor Antanas Mockus shook up the civic culture, trying out creative ideas drawn from his background in theater, philosophy and mathematics. For example, instead of cracking down on traffic rule-breakers with police action, Mockus started singling them out with a touch of humor, using clowns and mimes and installing Hollywood-inspired ‘walk-of-shame’ stars on spots that marked accidents. The success of such unconventional interventions revealed that he had touched on deeply held mindsets: the prospect of public shaming turned out to be a better deterrent in the people’s minds than monetary fines and threats of jail time. Mockus effectively took a law and order problem and reframed it as a social issue, using design interventions.

Step 3. Communicate rules in ways that help decision-making in unforeseen situations.

To communicate guiding rules, it is important to strike a delicate balance between instruction and inspiration. Keep in mind these three important characteristics:

In closing

We cannot live our lives either by total prescription or in a total absence of principles. But our organizations often make the mistake of hewing too close to either extreme. When we expect the data to always tell us what to do, or when we think innovation is all about indiscriminate trial and error, we are ignoring the hybrid, “art-meets-science” nature of great decision-making.

Kingshuk Das is Strategy Lead at Jump Associates, based in San Mateo, California.

First Published: Oct 31, 2012, 06:02

Subscribe Now