Sumant Sinha, Rahul Munjal emerge as poster boys of India's renewable energy sec

Through their ambition, backed by entrepreneurial acumen, both have demonstrated that caring for the environment can be good business

Sumant Sinha, chairman and CEO of ReNew Power Venture

Image: Amit Verma

This is a tale of two entrepreneurs. Though they took different paths to get there, both of them have emerged as the most recognisable faces of entrepreneurship in the Indian renewable energy sector.

One is the son of India’s former finance minister the other is the scion of a respected business group renowned for the motorcycles they make. One cut his teeth in the financial world as an investment banker in the US and UK the other started his entrepreneurial career through a chain of payment collection centres in the pre-digital wallets era. One of them first thought about his present venture when he was the chief financial officer of another company the other was passionate about his current line of work from his boarding school days.

Traversing on different paths, Sumant Sinha, chairman and chief executive officer of ReNew Power Ventures, and Rahul Munjal, chairman and managing director of Hero Future Energies (HFE), found common ground in their belief that doing well by the environment can also mean doing well by shareholders.

ReNew is India’s largest independent renewable power producer with an installed capacity of 2 GW (1 GW is equal to 1,000 MW) as on March 31 and Sinha says his company plans to add another 1 GW in 2017-18 across wind and solar power. It was the first independent power company in India to reach the 1 GW milestone, which it did in FY16.

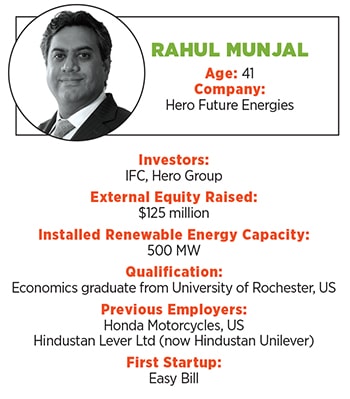

Hero Future Energies is rapidly getting to where ReNew was a year ago. The power producer has a current installed capacity of over 500 MW. It is working towards getting to the 1 GW milestone by August and by 2020, HFE intends to have a 2.5 GW capacity.

Sinha and Munjal, both based in the National Capital Region, exemplify the potential of India’s renewable energy sector that has allowed new entrepreneurs to dream big and create large-scale clean energy assets.

Sinha, the son of former finance minister Yashwant Sinha, had a long and impressive professional career before he decided to turn entrepreneur. The entrepreneurial bug bit him when he was working as the chief operating officer of Suzlon Energy, the wind turbine maker led by Tulsi Tanti. During his stint (2008-10), Sinha was also in charge of the company’s finances. The decision to join Suzlon proved to be life-defining for Sinha who, between 2002 and 2007, was the group chief financial officer of the Kumar Mangalam Birla-led Aditya Birla Group where he also set up and was the founder CEO of Aditya Birla Retail.

Rahul Munjal, chairman and MD of Hero Future Energies

Image: Amit Verma

When I was contacted by someone looking to hire for Suzlon, it got me thinking about the whole issue of climate change,” says the 52-year-old Sinha. “Back in 2007, Suzlon had a market capitalisation of $15 billion. That was impressive and I thought there was a lot I could learn by working for a company like Suzlon and a person like Tulsi Tanti.”

Soon after Sinha joined Suzlon in 2008, the global financial crisis hit and, among other things, it roiled Suzlon’s fortunes as its business in the US was affected and a debt-laden global expansion programme into markets like Europe went wrong. Moreover, some of the wind turbine blades made and sold by the Pune-based company to US customers suffered cracks, which impacted its reputation.

Suzlon’s business has recovered since, largely a result of Tanti’s willingness to take adversity on the chin and do what’s right by the business, including the divestment of the company’s crown jewels like German firm Senvion. But Tanti gives due credit for the turnaround to Sinha as well. “During our difficult period between 2008 and 2010, Sumant added a lot of value to the company by optimising our financial structure that helped us withstand the crisis,” says Tanti. “As a professional responsible for interacting with the market on behalf of Suzlon and handling the company’s finances, Sumant displayed great leadership and people management skills.”Sinha, for his part, attributes his understanding of entrepreneurship and the clean energy business to his time at Suzlon. “I developed a deep understanding of the technical, commercial and product development side of the business when I was dealing with the blade-crack issue,” he says. “The foremost entrepreneurial lesson I learnt from Tulsi Tanti was that of perseverance and resilience. He got knocked down so many times, but he just kept coming back. We used to wonder: My God! Where is this person getting this passion from to keep carrying on?”

Apart from resilience, the hallmark of a good entrepreneur is the ability to take risks. That was never an impediment for 41-year-old Rahul Munjal. After all, his family started by making bicycle components in Ludhiana in Punjab and went on to become the world’s largest two-wheeler manufacturer. He is Hero Group founder Brijmohan Lall Munjal’s grandson and the son of Raman Kant Munjal.

Munjal could have joined his family’s thriving business but three factors led him to carve out his own niche—his concern for the environment, the desire to do something that was at the cusp of being a service and, at the same time, manufacturing, and the Munjal family’s tradition of encouraging GenNext members to do their own thing.

Before founding HFE in 2012, Munjal launched another startup called Easy Bill, a chain of retail stores that served as financial transaction centres through which customers could pay utility bills and so on. This was before the era of digital wallets, and Munjal managed to scale this venture up to 20,000 centres across India. While Easy Bill still exists and a management team is figuring out how this business will evolve over time, Munjal’s attention is singularly dedicated to his second brainchild, HFE.

“At the Hero Group, we encourage the younger generation to explore new businesses with measured risks and diversify. Over the years, Rahul has refined his business acumen while following his own path. His early venture, Easy Bill, was ahead of its time,” says Rahul’s uncle Pawan Kant Munjal, managing director and chief executive officer of Hero MotoCorp, in an email.

His concern for the environment, which took shape during his days at the Welham Boys’ School in Dehradun, and his experience of dealing with state-run power distribution companies (discom) while incubating Easy Bill led to the foundation of HFE. “We were in class VII or VIII, when our principal—who was extremely forward thinking—got solar water heaters installed in school,” Munjal recalls. “I remember myself, even at that time, keenly listening to him and trying to understand how these heaters worked.”Years later, when Munjal was trying to get discoms on board to accept bill payments made by users through Easy Bill outlets, he observed the value chain and assessed where he could create additional value in the power sector. Discoms in India are mandated by the government to purchase a certain portion of their power requirement from renewable sources. Munjal immediately knew this was the business he wanted to be in.

Munjal agrees that belonging to an established business family helped: It gave him the requisite access to capital and the professional network that got the wind turbine turning at HFE. But convincing a professional family board like that of the Munjals’ is easier said than done. “It is a mix of logic and emotions that is at play when you go before a family board to seek capital for a new venture,” says Munjal. “While it is an extremely professional committee that approves of business plans and gives directions, they are also family members and owners, who have the right to be emotional.”

Munjal declines to cite instances where such “emotions” have posed challenges. But he drops a hint when he says with a smile that while doing business with other group entities was always a part of HFE’s plans, this customer base comprised the “toughest negotiators”.

For Sinha, as a first-generation businessman, the challenge was to raise capital to fund growth. He managed to cobble together some funds from his life’s savings to bag a portfolio of 120 MW to start with, but soon realised the need for additional funds to grow the business sustainably.

Armed with his experience in finance at large Indian companies and global financial institutions like Citibank, Sinha was all set to hit the road to raise finances when a retinal detachment left him bedridden for a couple of months. When Sinha finally got down to knocking on investors’ doors in June 2011, his experience and network made them answer his call, but not many were eager to pump in money readily. ReNew was looking to raise $60-70 million at that stage, which was too big a sum for an early-stage fund and too small for a large private equity player, Sinha says.  ReNew is India’s largest independent renewable power producer with an installed capacity of 2 GW as on March 31

ReNew is India’s largest independent renewable power producer with an installed capacity of 2 GW as on March 31

But his persistence paid off when his acquaintance Sonjoy Chatterjee, who had then just joined Goldman Sachs from ICICI Bank to co-head its Indian operations, put him in touch with the global investment bank’s private equity team.

It turned out that Goldman Sachs was looking to make some sizeable investments in India at that stage, keeping in line with its global theme of promoting clean energy companies. After two to three months of conversations, the global investment bank decided to invest in ReNew. “Their philosophy was energy is a capital-intensive business and they didn’t want the management team to run around looking to raise funds every now and then. So instead of $70 million, they wrote a cheque for $200 million!” says Sinha. “Of course, such a large investment came with a lot of bells and whistles,” he adds with a laugh.

ReNew has since raised a total of $850 million in equity funding to date. Goldman Sachs remains the largest investor in the company, and has in fact helped ReNew raise additional capital from other global marquee investors (see box). The company also recently raised $450 million of debt through masala bonds, which is a rupee-denominated debt instrument issued outside India.

Ankur Ambika Sahu, co-head of Goldman Sachs’ merchant banking division in the Asia Pacific, says that his firm was looking to invest in a profitable company in India’s clean energy space with proper checks and controls built into the organisation, and ReNew presented the perfect opportunity. “ReNew has a well-incentivised management team with a lot of execution experience coupled with strong corporate governance standards,” says Sahu, a director on ReNew’s board, over the phone from Tokyo. “In addition to his entrepreneurial spirit, Sumant’s integrity and intellect are of high calibre.” Hero Future Energies aims to reach the 1 GW milestone by August, from the current installed capacity of over 500 MWFor the last 12-18 months, global capital has been keenly looking to invest in the Indian renewable energy space, given the growing demand and a governmental push for clean energy in India. One of the significant transactions to take place in this calendar year was in January when International Finance Corp (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group, invested $125 million for an undisclosed stake in HFE. For Munjal, access to proprietary capital wasn’t an issue, but he wanted external validation for his venture, and didn’t want it to be seen as a business bankrolled solely by the Munjal family’s wealth, just because he was a part of it.

Hero Future Energies aims to reach the 1 GW milestone by August, from the current installed capacity of over 500 MWFor the last 12-18 months, global capital has been keenly looking to invest in the Indian renewable energy space, given the growing demand and a governmental push for clean energy in India. One of the significant transactions to take place in this calendar year was in January when International Finance Corp (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group, invested $125 million for an undisclosed stake in HFE. For Munjal, access to proprietary capital wasn’t an issue, but he wanted external validation for his venture, and didn’t want it to be seen as a business bankrolled solely by the Munjal family’s wealth, just because he was a part of it.

Shalabh Tandon, India Lead, Climate Business and Infrastructure, at IFC, says that strong ethical values, robust corporate governance and aligned interests of ramping up clean energy installations in the country were some of the key reasons for IFC to invest in HFE. “A strong leader is imperative to ensure a successful business,” Tandon says in an email. “We believe Rahul is leading the company in the right direction by being deeply involved in the operations. In addition, giving flexibility and a free-hand to senior company officials is a laudable trait which helps in executing strategies.”

While neither ReNew nor HFE disclose their financials, a back-of-the-envelope calculation using an industry thumb rule—that 1 MW of clean energy yields an Ebitda of Rs1 crore—shows that ReNew’s operating profit, with 2 GW of installed capacity, could have an annual run rate of Rs2,000 crore. In the renewable energy business, Ebitda is typically 85-90 percent of revenue (since there is no fuel cost), which implies a potential turnover of around Rs2,353 crore.

Similarly, HFE’s 12-month turnover, with an installed capacity of 500 MW, could be in the region of Rs600 crore, with an operating profit of Rs500 crore.

Both Sinha and Munjal have aspirations of going global and replicating their domestic success in other countries that are looking towards India’s low-cost renewable energy model for inspiration. In the process, ReNew and HFE will look to leverage the synergy of their partnership with Goldman Sachs and IFC respectively, both investors being global heavyweights.

After becoming one of India’s largest clean energy developers, Sinha now wants ReNew to be one of the world’s largest in terms of installed capacity (including in India and outside). Munjal has targeted HFE to be among the top three players in India.

For Tanti (who does business with ReNew) and Pawan Kant Munjal, ReNew and HFE’s success is strategic in nature. “As a group, we are committed to Hero Future Energies to ensure it becomes one of the top three renewable energy companies in the country,” Pawan Kant Munjal says of his nephew’s venture. “The (Hero) group has been diversifying its risk profile by investing in businesses with completely different risk associations. The renewable energy business is an annuity business which complements the group’s other businesses.”

Tanti’s interest lies in growing the independent power producers’ base in India, which would result in growing demand for the wind power equipment his company makes. “When he wanted to start up on his own, I supported him fully since we need people like Sumant to market the country and the sector to global investors,” Tanti says of his former colleague.

As India inches towards a targeted 175 GW of green energy production by 2022, the renewable power sector is up for grabs, and Sinha and Munjal have already staked their claim.

First Published: May 30, 2017, 08:26

Subscribe Now