The nature of fashion

An exhibition in London explores the relationship between nature and European fashion, and how the industry could become a more sustainable one

Exhibits at Fashioned from Nature include an outfit made from leather off-cuts and surplus yarn, Katie Jones, 2017, a jacket and skirt from Bruno Pieters’ Honest By, and a dress made with Vegea, a leather alternative Image by: Victoria and Albert Museum London

Exhibits at Fashioned from Nature include an outfit made from leather off-cuts and surplus yarn, Katie Jones, 2017, a jacket and skirt from Bruno Pieters’ Honest By, and a dress made with Vegea, a leather alternative Image by: Victoria and Albert Museum London

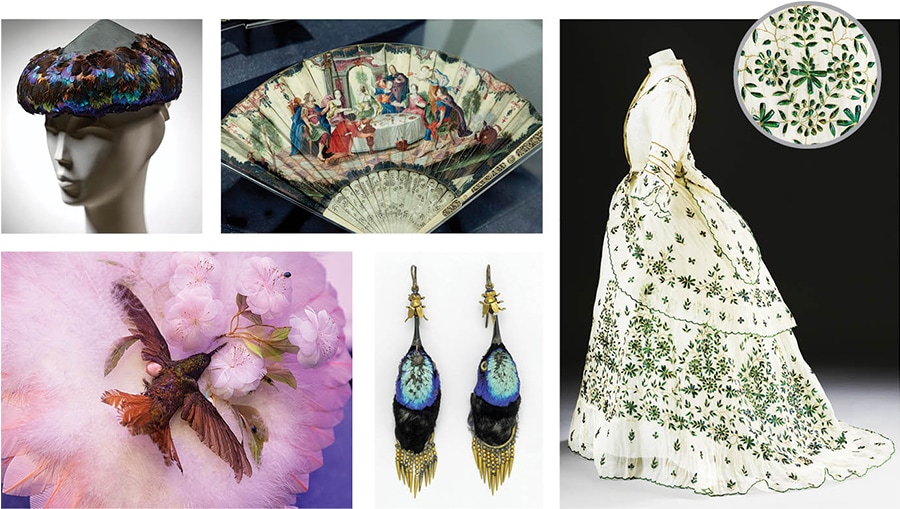

In 1859, the style-setting Empress Eugenie, wife of Napoleon III of France, wore a bonnet decorated with a stuffed hummingbird, setting off a fashion fad of using small birds to decorate dresses and hats. Bird parts and feathers had been used to dress hair, bonnets, ball gowns and accessories in Europe since the 1770s even entire birds were used in 1829-30, when birds-of-paradise appeared on hats as a novelty. But the French queen reignited the fad of using small birds like hummingbirds, tanagers, swallows and robins, and, needless to say, it led to the death of millions of birds.

“Fashion designers also often try to improve on nature to make it more pleasing to the human eye, and rarer,” writes Edwina Ehrman, curator of Fashioned from Nature, an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, in an email interview. “An example of this in the exhibition is a late 19th century hat decorated with a starling. The bird has had its feathers supplemented with those of another bird, probably a goose or swan, and the hat maker has arranged the bleached, dyed and painted feathers to suggest a larger, more exotic species.”

With around 380 exhibits, mostly from Europe, the exhibition, which opened on April 21 and will run till January 27, 2019, explores the complex relationship between European fashion and the natural world since 1600. A Greenpeace printed cotton T-shirt While nature dictates fashion cycles through seasons, it has also inspired fashion in various ways. The work of botanical painters, for instance, provided butterflies, flowers and insects as common embroidery motifs, while printed cotton chintz from India—which drew heavily on floral patterns—was much in demand. “Textile patterns have drawn on the natural world for centuries, certainly long before the advent of printing. But in Western European fashion, printed books on natural history and gardening became a key source, which are still important today,” says Ehrman.

A Greenpeace printed cotton T-shirt While nature dictates fashion cycles through seasons, it has also inspired fashion in various ways. The work of botanical painters, for instance, provided butterflies, flowers and insects as common embroidery motifs, while printed cotton chintz from India—which drew heavily on floral patterns—was much in demand. “Textile patterns have drawn on the natural world for centuries, certainly long before the advent of printing. But in Western European fashion, printed books on natural history and gardening became a key source, which are still important today,” says Ehrman.

A Gucci handbag designed by Alessandro Michele for the autumn-winter collection in 2017, which is screen-printed with a pair of male stag beetles copied from a natural history book written by Thomas Moffett in 1634, is part of the exhibition. Other designers, too, have used nature in a more personal and reflective manner. Christian Dior’s signature look comes from his first collection and the Corelle line: It features a narrow stem-like torso that bursts into full skirts like a flower. While Alexander McQueen often highlighted the more sombre aspects of nature: His last appearance in 2009, for the spring summer 2010 collection, addressed Charles Darwin’s evolution theories, along with global warming concerns.

A Gucci handbag designed by Alessandro Michele, which is screen-printed with a pair of male stag beetles Fashion has also taken from nature—not just raw materials like cotton and silk to make the second skin that humans wear but, over various periods, materials like whalebone, sealskin, furs, turtleshell, ivory, reptile skins as well as beetle wings, prized for their iridescence. In the 1800s, beetle wing cases were exported from India, as well as stoles, dress panels and flounces embroidered with beetle wings. The brilliantly coloured, iridescent feathers of the male monal pheasant, native to Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar and China, were another prized decoration.

If these also sound like a list of banned materials and protected species, it’s because they probably are. Each seasonal, cyclic fad led to the destruction and killing of species, prompting corrective action. “From 1890 to 1910, when Canadian seal-hunting was particularly intensive, the population of northern fur seals was reduced from 5 million to some 300,000. In 1911, an international treaty gave them protected status,” says Ehrman.

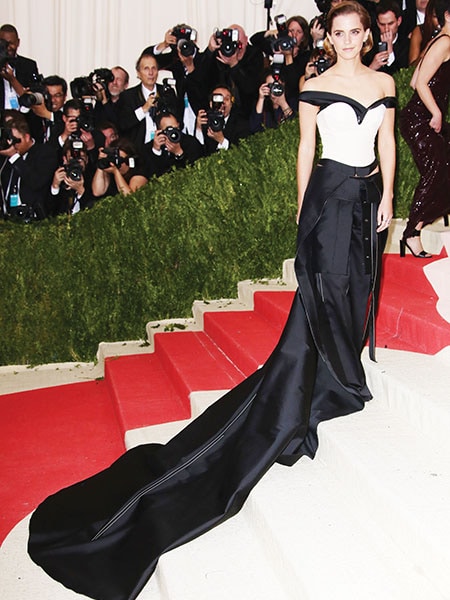

A Calvin Klein Green Carpet Challenge dress, made from recycled plastic bottles, worn by actor Emma Watson to the Met Gala in 2016The fashion industry’s demand for raw materials, constantly rising, has had an impact not just on animal populations but also on the environment. That’s why Ehrman decided to focus, along with nature, also on the problems caused by the industry and on sustainability as she became increasingly aware of the growing number of national and global initiatives—such as the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris, and the 2015 report by the United Nations Environment Programme which outlined excessive consumption as a major cause of environmental degradation—to reduce its environmental and social impact, and make it more sustainable.“I felt we were reaching a tipping point in public opinion, and that the time was right to be bold and use the exhibition to explore the causes, effects and solutions for the challenges we face today,” she says, adding that during the course of curating and researching for the exhibition, she was shocked by some of the industry statistics, particularly its pollution rating. “We have been conservative in placing it as one of the top five polluters. Some say it is the second most polluting industry on the planet.”

Dyeing of textiles has always caused water pollution, but with the rise of fast fashion and technology, other factors like land, air and people, come into play. “Fast fashion responds rapidly to consumer demand, with ever more efficient production and supply chains encouraging larger wardrobes and the notion of ‘disposable’ fashion. The business model has also ratcheted up the industry’s environmental impact,” says Ehrman. Between 2000 and 2014, global clothing production doubled, and a 2017 study by The Global Fashion Agenda in collaboration with The Boston Consulting Group projected fashion consumption to rise a further 63 percent by 2030.  (Clockwise from top left) A hat made of monal pheasant feathers a hand fan made with carved ivory sticks a cotton muslin bodice and skirt decorated with beetle wing cases earrings made from heads of Red-legged honeycreeper birds a feather fan decorated with a stuffed hummingbird and jewel beetles

(Clockwise from top left) A hat made of monal pheasant feathers a hand fan made with carved ivory sticks a cotton muslin bodice and skirt decorated with beetle wing cases earrings made from heads of Red-legged honeycreeper birds a feather fan decorated with a stuffed hummingbird and jewel beetles

The industry’s various initiatives to reduce its environmental impact are highlighted at the exhibition. They range from designers using innovative materials—a dress made with Vegea, a leather alternative made from grape waste a Ferragamo ensemble made from ‘Orange Fiber’ derived from the Italian citrus industry’s waste and actor Emma Watson’s Calvin Klein dress made from recycled plastic bottles—to brands committing to use organic and sustainable practices and in the case of Patagonia, even asking consumers to buy less. During the 2011 Black Friday sale in the US, the outdoor clothing company ran an advertisement in The New York Times with an image of one of their jackets and the line ‘Don’t buy this jacket’, suggesting that buyers might have enough.

Other initiatives by brands include transparency: Bruno Pieters’ Honest By and London-based designer Martine Jarlgaard are making their garments’ production history and impact available to consumers: Honest By publishes the information on its website, while others have ‘smart labels’ that can be scanned to trace a garment’s journey.

The challenge fashion faces is enormous, says Ehrman, but governments, industry, business, science and design are coming together to find solutions. “Recycling and reusing to dramatically reduce fashion’s utilisation of virgin raw materials, and cutting down its consumption of water, chemicals and fossil fuels, are priorities. Consumers are also increasingly aware and responsive to the need for change and we need to build on their potential power to demand better.”

First Published: Jun 02, 2018, 07:00

Subscribe Now