Taming The Golden Mahseer In The Himalayas

Learning how to catch the golden mahseer, the king of freshwater game-fish in India, is a lure that's very hard to resist

So you tell your girlfriend that you’re going to take her angling: to the same river pool where Jim Corbett was pulled headlong into the water by a mahseer which, in his own words, “suddenly galvanised into life, and with a mighty splash dashed upstream” (Man Eaters of Kumaon, 1944). “Isn’t that a carp?” she says condescendingly. “We’re going to fish for carp?” The sneer is clear: sluggish hours spent beside a river, after which (if the bait is taken) the hapless fish is hauled out of the water.

Rudyard Kipling would have been mortified by the comparison: in his story ‘The Brushwood Boy,’ Georgie, the soldier-protagonist, meets ‘the mahseer of the Poonch beside whom the tarpon is a herring, and he who lands him can say that he is a fisherman.’ With its golden scales and projectile-shaped body, the mahseer resembles the unrelated tarpon more than its distant cousin, the carp. But the mahseer leads no sedate life: energetic rivers make it speedy, strong and full of wile. Make no mistake, it is a thoroughbred filly to the carp’s plough horse. Corbett himself considered “fishing for mahseer in a submontane river the most fascinating of all field sports…a sport fit for kings.”

(You are guilty of some manipulation of facts: Marchula isn’t where Corbett’s encounter with the mahseer occurred—that was on the Mahakali River in upper Kumaon—but the hamlet does lie on the periphery of the Corbett National Park, and the Ramganga, which flows through it, is one of the last natural habitats for the golden mahseer.) Image: Jim Klug

Image: Jim Klug

The angler never forgets his first encounter with the mahseer. It is an electrifying experience

Faced with this flash-flood of facts, your girlfriend dials down the scorn, but isn’t convinced that you’re serious, not even when you buy copious quantities of insect-repellent and a knock-off fishing jacket. It’s only when you dump the luggage into the cavernous insides of a borrowed SUV that she accepts the reality.

After an eight-hour drive, you are at the foothills of Kumaon. You ford the Ramganga with some aplomb, thanks to your suave mini-truck (not recommended in any vehicle with low clearance) and arrive at your campsite, hallowed ground for fly-fishers in North India.

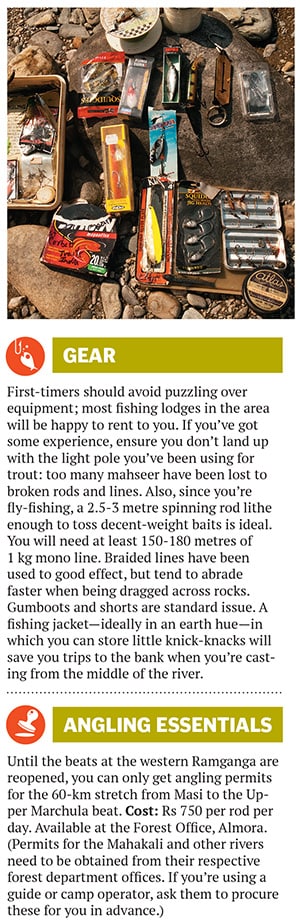

You disembark, resplendent in camouflage jackets, festooned with rods still gleaming in their packaging and a tackle box with an ‘Anglers unite’ sticker.

A group of veterans observe your arrival with some amusement. “Very pretty tackle!” (this is Gauri Rana, your host) “But these couldn’t lure a bottom-feeder here, let alone a mahseer. And unless you want to spook all the mahseer along the entire stretch, lose the jacket.”

Fish, we learn (and especially the mahseer), aren’t particularly global in their tastes. So that tackle, which the ad in Anglers Monthly guaranteed would have a shoal tripping over itself, is “too foreign” here.

The Ramganga extends from the lower Himalayas in Garhwal, past Marchula, into Corbett National Park its run is abruptly stymied by a dam at Kalagarh on the Garhwal border.

You’ve got legal sanction to try your luck on 60 km of this stretch: from the village of Masi down to the Upper Marchula ‘beat’ (a fishing term which denotes a stretch of water fished by an angler. Popular angling rivers have multiple beats)— just over a 1.5 kilometre upstream from Rana’s ramshackle camp.The three fishing beats here—Marchula, Jamun and Vanghat—once teemed with anglers. But in 2010, the river broke its banks and washed away large swathes of land. The government promptly banned fishing there, leaving only the stretch which falls outside the boundaries of the national park open to anglers.

Rana’s camp was destroyed too only one structure and a bevy of tents are left. “This isn’t a commercial establishment. You pay as you go, and no one’s going to come after you if you decide to take an ill-advised night stroll in the woods,” he says.

The group you join for a coarse meal isn’t talkative. Your smooth conversation-starter elicits a few snickers before the discussion returns to Virgil on how to read the weather, based on animal, bird and insect behaviour.

You remember the story you’ve heard recently, about Jim Currier—an American professional angler—pulling in a 23-kilogram mahseer on the Mahakali. He was with well-known local angler, Misty Dhillon, who runs a fishing lodge above the Upper Marchula beat, where you will head for your first sortie on the river. “The angler never forgets his first encounter with the mahseer: a great wrench on the rod heralds its take, then the ratchet screams on a fast-emptying reel. The sensation is electrifying. Few freshwater fish will set off with such speed, fight for long and strike both despondency and joy to the heart of the adversary.”

You have no such experience the next day. The waters at the Upper Marchula Beat, which you’re led to by Anand—the most well-known angling guide in the region—are crystal-clear. (‘Gin-clear water’: that Corbett phrase sticks out but you only end up visualising what your last gin and tonic looked like.) So clear that you can see the occasional mahseer under the surface trouble is, they can see you too.

Your girlfriend takes to fly-casting much quicker than you do. She is genetically hard-wired, it seems, to actually cast the bait more than three metres away. No one is surprised when her bait is taken in a shallow pool just beyond a section of the rapids. It’s a small mahseer, a 2.5-kilogram male which takes 20 minutes of reeling and coaxing to point its tail upwards in the water, mahseer-speak for a white flag. If she is thrilled about catching one, she is even more eager to release it, and the finned denizen is quickly returned to the river. Not that there was a choice—angling at the Ramganga is strictly catch and release.You have a close call at the same spot next morning, when Anand attaches a traditional lure—a hammered brass spoon—to your line. A vicious yank, the rod bends and, before you know, the hook’s been pulled almost 90 metres downriver. You think you’ve landed the biggest mahseer, but the fish, when it jumps and snaps the line, appears no heftier than three kilograms. It’s a quick first lesson: even a relatively small mahseer will punch above its weight when it’s in water. Brute strength is folly you’ll just snap the line and lose the fish.

The mahseer’s future in Kumaon isn’t promising. When others of the same species spawn happily in still waters, like those at Naini Lake, biologists haven’t cracked the enigma of why this breed chooses an energy-sapping upstream migration. Especially since, breeding imperative or not, they must run the gauntlet of artificial channels and stone embankments (known as ‘thokars’) and unscrupulous poachers. Rana, who’s been angling at Marchula for over three decades, says there’s been a noticeable depletion in numbers since 2010. Fewer tourists and no anglers means bleaching, poisoning and dynamiting along stretches of the river are not unheard of. And there’s been a loss of livelihood for locals like Anand, who had a vested interest in the conservation of the fish. Dhillon runs his fly-fishing classes at the beat below his resort, but now prefers to take groups on angling trips upriver.

Sobered by these thoughts, you make your way back to the camp for your last night on the Ramganga. You forget that not five years have passed since the river swept away the camp here and that if it happened now, the forest you’d run into teems with elephants, snakes and big cats.

The first stars are out. The hoots of owl rise in crescendo, and frogs chant more hypnotically than a monastery full of monks. Nirvana is within touching distance.

“Darling,” your girlfriend says, as she snuggles up to you later that night, “You know, I think you make dodgy decisions. But you made the right call coming here. Angling for the mahseer is the most adventurous thing we’ve ever done.”

Disclaimer: Volvo India provided a vehicle to the author for the duration of his trip

First Published: Jul 21, 2014, 06:16

Subscribe Now