Shabana Azmi On Classiness in Cinema

Often, the Indianism ‘filmi’ is used to mean the very opposite of class. Its shades of meaning include an artificiality, a certain amount of exaggeration, of façade. Class, to survive in this hurly-bu

I can’t call myself classy, it’s for other people to say that. I can only say that this is what I have seen, this is what I have imbibed, and this is how I am. Class is intangible, almost indefinable. It is a summing up of the parts so that they become more than the whole. It has to do with dignity, subtlety, with a layered subtext where much more is expressed because it is hidden. It’s got very little to with wealth and money, and much more to do with an attitude that comes from being comfortable in your own skin.

All of us, in certain situations, want to put on our best self. But it’s when you’re not doing it for public consumption that counts. Like eating. When I’m by myself and nobody’s watching, do I gobble up my food? Do I eat it elegantly? Do I behave in the same way when there are people for whom I want to put my best foot forward?

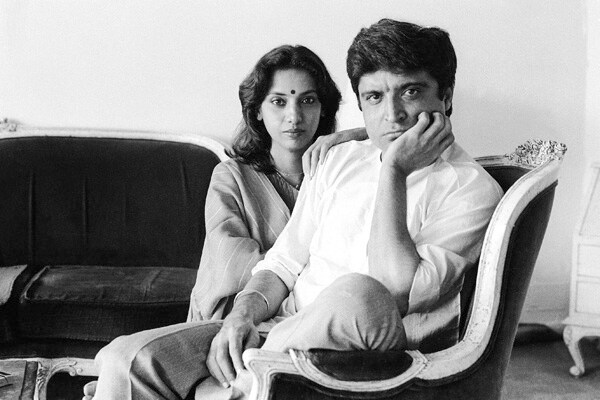

My father was very classy. My husband is very classy. An unspoken aesthetic touches everything they did or do.

My parents have been the two most important anchors in my life they taught by example. Both of them were public people with public personas, but they also had private personas not disconnected from the public ones.

My father was a member of the Communist Party. We grew up with eight families sharing one toilet. A 225-square-foot tenement was home. And yet my entire upbringing was peopled by intellectuals of the highest order: The biggest poets, writers, theatre people, some from film, the working class, all of that. The governor of Maharashtra would come in to meet my father, and a labourer without any chappals, and both would have access to the house. In retrospect—not then—for my brother Baba and I, money really wasn’t the most important thing there were other values which were greater. And that formed the kind of people we are.

I watch my mother a lot—I think she is a very classy lady—and I see that she dresses for the sheer joy of her own satisfaction not for anybody’s sake. The way she eats food, the way she orders food, the way she is—her very persona is that of an extremely classy person. There could be many others who have much more in terms of wealth who would not be able to do it.

And Javed has been a huge influence we’ve been married now for 27 years. My mother says the UP mard is a different phenomenon altogether: Very high on propriety, on how you should behave with seniors, with adults, how certain words are not to be used with certain people, how any kind of crassness, even in humour, is not acceptable. In many, many ways, Javed is a lot like my father, because they have exactly the same kind of background.

I think most of us attribute class to people in high positions, to the rich. The more discerning of us realise that is not true.

To me, Lakshmi, whom I played in Shyam Benegal’s Ankur, my very first film, is classy. She is a farmhand who gets seduced by the landlord. She accepts that position until finally she finds the guts to speak out against him. Her husband has abandoned her she has to steal rice, and is caught by the landlord’s wife. And to prove that he has nothing to do with Lakshmi, he really screams at her, humiliates her in public. She walks away, with just a look, which really skins him. To me that’s a classy act.

And Jamini, the role I played in Khandhar, is a young woman with absolutely nothing to look forward to. Her mother is blind and paralysed, and Jamini knows there’s not a chance in hell she’s going to get married. Someone who has promised his hand to her has disappeared and she knows he will never come back, but the mother lives in hope. Along comes a man, played by Naseeruddin Shah, and the mother presumes it is that boy who has come back. And she says, you will marry her, will you not? And he gets pushed into saying yes. Despite herself, it ignites hope in Jamini. She could have clung to him, because she was really, really desperately lonely. But she knows the man has been pushed into that situation, and though she would very much want to be with him, she lets him go. She is really one of my favourite characters: She could quite easily have become a victim, but she conducts herself with such dignity. It’s really poignant, deeply moving. That’s such tremendous class.

I work in the slums, in the village. And I come across many, many women whom you would not define as classy in the sense that you would a Gayatri Devi. Yet there’s a core to them, where they are able to hold on to their dignity under great adversity. They’ve got class. It’s also got to do with strength, with your ability to negotiate life. It comes from your values, what you hold dear.

Balraj Sahni is an actor who brought class to anything that he did. He would invest even the most corny lines of mainstream cinema with a lot of dignity, and thereby redeem them.

Then there’s Shyam Benegal, who has been a guru to me. He shaped my aesthetics, my love of cinema (although I came from the Film Institute). When we travelled abroad, others would always rush off to start shopping madly. Shyam? Right from the airport, when he was sitting in the car, the kind of enquiries he would make about the city were completely different from anyone else’s. He was interested in going to the museums, to the gardens he was interested in the history of the place. My eyes today, when I look at a new city, are defined by the way Shyam, subliminally, made me see. It’s the wholeness of his persona, the lack of meanness, the generosity with which he encourages young people… all of that is class.

Shashi Kapoor, Jennifer Kapoor… I think everything that they did was classy. As a producer, Shashi treated his crew with immense respect he would take care of the most disempowered person.

A very strong hierarchy dominates the film set: The spotboy is treated differently from the star. I think your class shows more in the way you treat the spotboy, not the star. But things like different food being served to people in different strata are changing, mercifully, with the younger generation. At the shoots of Zoya and Farhan, my kids, everybody eats the same food, stays in the same kind of place—there are categories, but everybody lives together.

It’s very difficult, when you’re peaking as a star, to remain classy. You cannot even imagine what it’s like to have millions of people swooning just to look at you. It’s very, very difficult for somebody to keep her head on her shoulders when that happens. You’re surrounded by people who protect you, from life even. And it all becomes about the clothes that you wear, the parties you throw. All of it is nice, happy, but it’s not… enough. You need to have a real connect with life, people, to remain classy. Unless there is something in the way you were brought up, or somebody around you—your spouse, your partner—who is vigilant that you don’t lose your touch with reality, it’s easy to lose it.

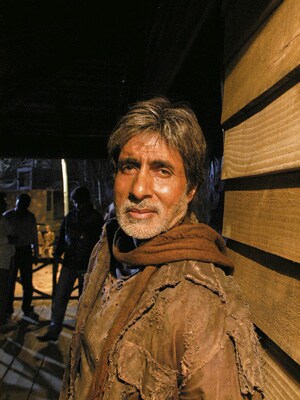

Amitabh Bachchan is classy, because it is almost impossible to handle the kind of success that he’s seen and be as well-behaved. He will reply to your SMS, return your call. Today’s stars often think it’s okay if they don’t respond to an SMS. Amitabh is careful enough to be sensitive to the people who are trying to reach out to him. It’s very difficult, when you’re as popular, as much in demand, to conduct yourself with grace. That’s what he does.

That’s class.

(As told to Peter Griffin)

First Published: Apr 23, 2012, 06:45

Subscribe Now