Oysters from Australia: Adding to the flavour on the plate

Along the southern coast of Australia's New South Wales are farms that ensure only the best oysters make their way to the plates of connoisseurs

The stick method of oyster farming has been replaced with more sustainable practices in Australia, including at Captain Sponge’s farm in Pambula

Images: Pramod Mathew

If not for the imposing sign at its entrance, the airport at Merimbula can easily be mistaken for a convenience store. I have just alighted from an hour-long flight connecting the coastal town, deep on the South Coast of Australia’s New South Wales, to Sydney.

Merimbula is where our adventure begins. The plan is to travel along the South Coast by road (back to Sydney), meet oyster farmers, savour oysters, and enjoy the coastline. I had had my first sip of an oyster in Sydney the previous day: The meat, floating in a juice called liquor, is jelly-like and can be slurped down. And now, it is time to find out where Sydneysiders get their helping of the luxury food from.

A short drive south of Merimbula is Pambula, a village of 1,000-odd people, where Brett Weingarth, 50, greets us at the jetty. Captain Sponge, as he is known, has been farming oysters for a decade in the Merimbula and Pambula lakes, where he also runs Captain Sponge’s Magical Oyster Tours. Aboard Sponge’s motorised punt, skipping over the Pambula Lake, I begin my crash course in oyster harvesting.

Long white poles, marked and numbered, become visible in the distance. They demarcate one farm from the other. Sponge owns 11 acres on the Pambula and Merimbula lakes, harvesting mainly the indigenous Sydney rock oysters—the most popular variety among premium restaurants—and, to a smaller extent, Angasi oysters.

“Oyster farming has come a long way from the ‘stick method’ that was employed up until seven or eight years ago,” says Weingarth. The stick method, once an industry mainstay, begins with oyster larvae setting on hardwood sticks (coated with tar to prevent the sticks from rotting) that are arranged like a rack in the water. The sticks catch the young oysters floating in the water. But, over time, the tar would leach out, polluting the river. Oysters take on the taste of the water they breed in. The meat sticks to the lower shell and has to be pried out before it can be slurped

Oysters take on the taste of the water they breed in. The meat sticks to the lower shell and has to be pried out before it can be slurped

This method also suffered from another flaw. “On the sticks, oysters would grow long and thin and non-uniform, and they also grow into each other,” says Weingarth. The stick method is now on its way out, and the uniform shape of oysters is the outcome of more sustainable farming. “Today, most farmers in the South Coast have replaced tar-treated sticks with slats,” says Weingarth, as he shows me a piece of flexible plastic that can easily be mistaken for a venetian blind. The slats don’t require any treatment. “The baby oysters suck onto the slats and then start growing their shells, feeding on the algae in the water.”

“Once they are 8 to 10 months old, juvenile oysters are removed from the slats,” continues Weingarth, as he twists the plastic to show how the creatures are stripped and transferred to meshed cylindrical tumblers. The waves rock the tumblers in the water, giving oysters their uniform deep cup shape, making them more appealing commercially.

When they grow bigger, the oysters are graded, based on their size, and transferred to floating, meshed bags, which float in pairs, one on top of the other. “The oysters in the top bag are dried by the sun and wind, maintaining their cleanliness, and once every six days flipped over so that oysters in the second bag are also exposed to the sun,” explains Weingarth, leaning over into the lake to pull up one of the meshed bags.

Weingarth sells 20,000 dozen mature oysters—from slat to plate is generally a three-year cycle—a year through the Australia’s Oyster Coast company, earning “between A$5.5-10 a dozen, depending on the size”.

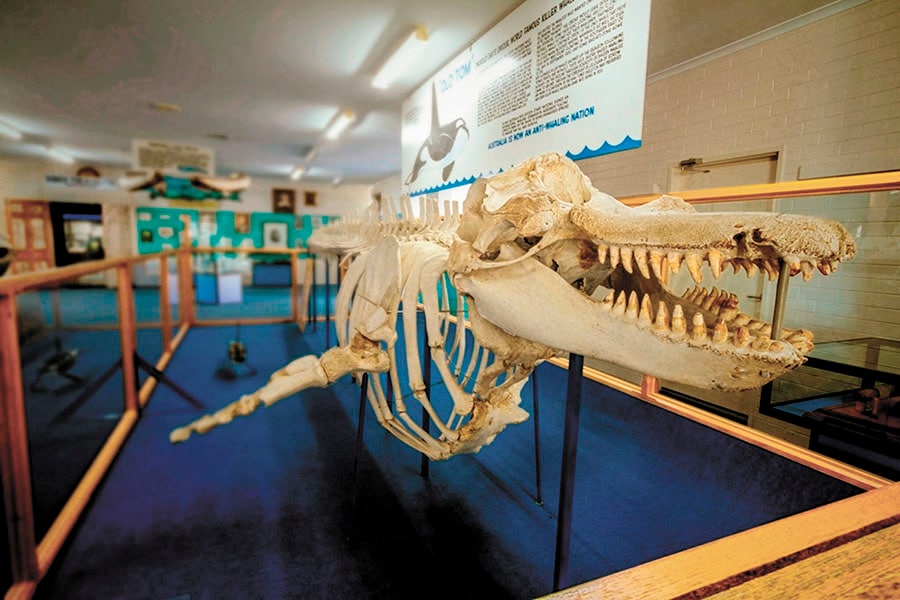

Some of the oysters he pulls out of the bag are mature (you can tell by their size), and Weingarth separates them from those that should return to the lake.  Killer whale Old Tom’s skeleton at the Eden Killer Whale Museum

Killer whale Old Tom’s skeleton at the Eden Killer Whale Museum

Image: Eden Killer Whale Museum

“Farmers here have lost thousands of dollars’ worth of their catch to stingrays, because they didn’t have time to cover the bags [with a protective frame],” Weingarth says. Yet, contending with marine predators is trivial compared to the threat posed by humans. “Our greatest challenge is to maintain good water quality and educate those who live in the lake’s catchments [to not pollute],” he says. Oysters take on the taste of the water they breed in. “Each estuary has a different geochemistry and the [quality of the] fresh water changes the taste of the catch.”

Before we return to the jetty, Weingarth has a plateful of oysters for us. He wiggles a knife in between the creature’s shells and shucks (oysters are ‘shucked’, not ‘opened’) a Sydney rock oyster before discarding the top shell. The meat still sticks to the lower shell and has to be pried out before it can be slurped.

And does he get a prized pearl from his harvests? “Not terribly often, and we don’t attempt to seed them for that.”

The next farm on our itinerary was not until the following day, so, after lunch, we head further south to explore Eden. The historic town, with a population of just over 3,000, is home to the Eden Killer Whale Museum, which provides a perfect vantage point to view humpback whales as they migrate north to escape the icy Antarctic waters of June to August, and return with their newborn calves in September to October, the peak whale-watching season. Shane Buckley harvests Sydney rock oysters at his Wapengo Rocks farmGazing at Twofold Bay—which opens out into the South Pacific Ocean—from the viewing deck of the museum, it is evident why this town was the epicentre of whaling activity for over a century until 1931. Twofold Bay was once home to killer whales that hunted migrating baleen whales. “A shore-based whaling operation run by several generations of the Davidson family was the longest to operate in Eden,” writes Robert Sykes, business manager at the Eden Killer Whale Museum, in an email to Forbes India.

Shane Buckley harvests Sydney rock oysters at his Wapengo Rocks farmGazing at Twofold Bay—which opens out into the South Pacific Ocean—from the viewing deck of the museum, it is evident why this town was the epicentre of whaling activity for over a century until 1931. Twofold Bay was once home to killer whales that hunted migrating baleen whales. “A shore-based whaling operation run by several generations of the Davidson family was the longest to operate in Eden,” writes Robert Sykes, business manager at the Eden Killer Whale Museum, in an email to Forbes India.

The success of the Davidson family’s whaling business relied on their close association with killer whales. If a baleen whale came close to Twofold Bay, which falls on its migration path, a pod of killer whales would herd the much larger prey into the shallow waters. A member of the pod would swim into the bay and deliberately alert the Davidsons about the hunt by thrashing its tail. The whalers would then follow the killer whale to where the baleen whale was and harpoon it. The carcass of the baleen whale would be brought close to the shore and left overnight for the killers to feast on its tongue, while the Davidsons would get the blubber and the rest of the carcass.

“In 1930, the body of ‘Old Tom’ was found floating in Twofold Bay. It was the best known of the last of the killer whales that assisted the whalers before whaling declined. Its carcass was processed at the Davidsons’ whaling station and the skeleton preserved,” writes Sykes. Old Tom’s skeleton is still on display at the museum.

After spending the night at Merimbula, we head to Wapengo, an hour’s drive north, early next day. There, oyster farmer Shane Buckley, 48, awaits us. He harvests Sydney rock oysters at his Wapengo Rocks oyster farm—Australia’s only organically-certified farm—on the Wapengo Lake. Ewan McAsh’s Signature Oysters is a cooperative of sorts

Ewan McAsh’s Signature Oysters is a cooperative of sorts

The Mumbulla Mountain, visible from a distance, forms the catchment for the pristine waters that feed the Wapengo Lake, says the paramedic-turned-farmer, even as he shucks freshly-harvested oysters for us. Filtered by the surrounding state forests and salt marshes, the clean waters that flow into the Wapengo Lake ensure that the oysters here are the most sought-after among premium restaurants.

Buckley says it’s because of “merroir—the idea that the quality of the water and its ecology can have an effect on the flavour of the oyster”.

That’s why Sydney rock oysters from Wapengo have a flavour that’s “completely different—they’re intense, robust and, depending on the time of the year, creamy and rich. Fifteen minutes after eating the oyster, you’ll still be tasting it”. And it goes best with beer, he adds.

The taste is a result of Buckley’s efforts to phase out stick culture after he purchased his farm 10 years ago. His oyster tumblers and bags are also made of recyclable material, diminishing the farm’s waste output.

Buckley does not supply his crop wholesale it’s delivered directly to high-end restaurants in Melbourne, Canberra and Sydney. “The food culture has changed, people are now interested in where and how the product is grown,” he adds. Brett Weingarth, known as Captain Sponge, who has been farming oysters for a decadeThe organic certification makes his oysters approved for exports, but he has not ventured into it. “The logistics of getting them on a plane and the costs of building approved packaging facilities do not get compensated,” he explains.

Brett Weingarth, known as Captain Sponge, who has been farming oysters for a decadeThe organic certification makes his oysters approved for exports, but he has not ventured into it. “The logistics of getting them on a plane and the costs of building approved packaging facilities do not get compensated,” he explains.

Exporting oysters is capital intensive, and it’s possible only when farmers collaborate. At least that is how Ewan McAsh made it possible, through his collective venture Signature Oysters in Batemans Bay, two hours north of Wapengo. But his farm is on our itinerary only for the next day.

So we are free to explore the touristy spots between Wapengo and Batemans Bay, including the town of Bermagui. Among the town’s nearby attractions is the Blue Pool, a natural rock pool. Washed with clear ocean water, it’s a wonderful swimming spot located at the base of a rocky cliff face. You could also take a coastal bush walk near the cliff and take in spectacular views of the ocean and natural rock formations like the Camel Rock and the Horse Head Rock.

We retire for the night at Narooma. Our guide Sophia Chen had suggested a pre-dawn trip to Mill Bay Boardwalk and we are up early enough to see the sunrise through a freak of nature called the Australia Rock. The rock, as the name suggests, has a natural perforation shaped like the map of Australia. When the sun is up, you can see the waters of the bay, teem with seals hunting for fish.

Around noon, we arrive at McAsh Oysters farm, where Kevin McAsh, 68, is busy shucking oysters. The farm, which he bought in 2004, harvests Sydney rock oysters, Angasi rock oysters and Pacific rock oysters a year on the Clyde River. Like Weingarth and Buckley, he too replaced the stick method with more sustainable practices.

However, it is Signature Oysters, his son Ewan’s two-year-old venture, that is being called radical. Signature Oysters is a cooperative of sorts. “After running my own oyster bar, I realised that customers were interested in where their oysters were grown and by whom. I started Ewan McAsh Signature Oysters, selling directly to restaurants. But after a while, there was too much demand. So I started Signature Oysters and recruited 27 other farmers,” writes Ewan, 37, in an email to Forbes India.

Signature Oysters supplies to restaurants all over Australia, as well as in China, Hong Kong and Singapore. The Wapengo Rocks oyster farm also supplies to Ewan, who pays farmers “25 to 30 percent more than the wholesale market”. In return Ewan “gets a premium at Australia’s best restaurants” as he ensures that he sells only the best, by handpicking farmers with the best practices.

Before leaving the farm, Kevin McAsh lets me try my hand at shucking oysters, and I realise it cannot be done without considerable practice.

We are ready to continue our drive north to Sydney. But first, we make our way to neighbouring Pebbly Beach, and we realise we’ve entered kangaroo territory. Accustomed to humans, the marsupials happily pose for photographs.

Sydney is a four-hour drive from Pebbly Beach. But you don’t have to make the journey in one go: You could stop over at neighbouring Jervis Bay, which offers dolphin-watching cruises, or the coastal town of Mollymook, or the village of Berry.

As you can surmise, we had set out to uncover the mystery of oysters, but ended up with much more flavour on our plate.

(The writer travelled to New South Wales at the invitation of Tourism Australia)

First Published: Oct 28, 2017, 07:49

Subscribe Now