Indigo Nation: The colour of British oppression, and now of fashion

While the darker shade of blue has taken the world of fashion by storm, the dye that coloured India's resistance to the British is fading from mainstream consciousness

“Not a chest of Indigo reached England without being stained with human blood.”

EWL Tower, district magistrate of Faridpur (of undivided Bengal), 1860Indigo is having its moment in the sun. Look around you, and you are likely to find fashion labels—be it mainstream, niche or online—flaunting an indigo collection of sorts. The trend effortlessly transcends Western and Indian garments with the colour being used in everything, from Western formals and casuals to Indian ethnicwear and even home decor. This, apart from the ubiquitous indigo-coloured denims.

“We have had indigo garments in our collection for the past five to six years. But it is only in the past two years or so that it has become very popular,” says Krishna Thingbaijam, head of design at the Future Group, owner of Fashion at Big Bazaar (FBB). “Earlier, we would have about 10 new indigo outfits in a season, which means twice a year but now we have the same number of new outfits four times a year.”

The brand has extended the colour from the usual women’s ethnicwear to men’s as well. “The focus now is on indigo and prints,” adds Thingbaijam, a 16-year veteran of the company. “It is a versatile colour, and can be used in many forms.”

Says Charu Sharma, director of Fabindia, which launches an indigo collection every year, “Indigo has seen a huge resurgence the world over, from ramps dominated by designers to traditional designs and patterns. Every product category, from home to garments for men, women and even children, has responded to the call of indigo.”

Designer Neeru Kumar, who has worked with natural fibres and dyes for more than 20 years, too confirms indigo’s timeless appeal. “Indigo can never really be in fashion or out of fashion. It is as classic as black and white.” She, however, cautions that a revival of the colour does not necessarily imply a revival of the natural dye. “They are two very different things,” she adds.

FBB’s Thingbaijam believes that while in India, and other parts of Asia, the indigo dye (and hence the colour) has remained a part of traditional garments and colour schemes for centuries, the West’s love for the colour is borne more out of a novelty factor. But regardless of reasons, the universal appeal of the colour is evident from the fact that international brands such as Marks and Spencer, Joules, Unionmade and Vans have their own indigo collections, as do niche Indian brands such as Tulsi, Creative Bee, Jaypore, Aavaran and D’Art Studio. Fashion designers such as Priyadarshini Rao and Chirag Nainani showcased their indigo-inspired creations at this year’s Lakme Fashion Week, while designer Debashri Samanta and design label 11.11 showcased theirs at Amazon India Fashion Week.

India, at the moment, loves indigo. But this wasn’t always so.

One of the most common natural dyes historically used in, and traded from, the Indian sub-continent, indigo was one of the crucial exports of the British government. The significance of the dye can be understood from the writings of MN MacDonald in a 1900 issue of Pearson’s Magazine, an influential monthly publication started in 1896: “Today, nearly all the blue uniforms of our Navy and Army, and policemen and postmen, are dyed with the purest natural indigo, which resists bad weather and sea-water better than any other dye. For similar purposes, the United States demand as large a quantity as we do, while France, Germany, Italy and Russia are also extensive buyers of the Indian blue.”

The money that British planters made from the export of this invaluable natural dye, and their increasing use of coercion to extract the maximum possible amount of dye from the land, was at the centre of the first rural uprising in 1859-60. The nil bidroho (the Indigo Revolt), which was the result of more than half a century of brutally oppressive farming practices that peasants in Bengal and Bihar were subjected to, was chronicled by Dinabandhu Mitra in his seminal play Nil Darpan.

The peasants, forced into farming indigo—a plant that when cultivated continuously sapped the soil of all nutrients, rendering it barren—on fertile land meant for growing paddy, were even denied a fair price for the indigo they produced. Refusal to grow indigo would result in severe beatings, and burning down of their homes and farms. And although the price of agricultural produce increased almost two-fold in the course of the period, the farmer was deprived of any benefits of this increase they were not even paid their cost of cultivation. Consequently, the farmer neither had food from his own fields, nor the money to buy it, being reduced to abject destitution.

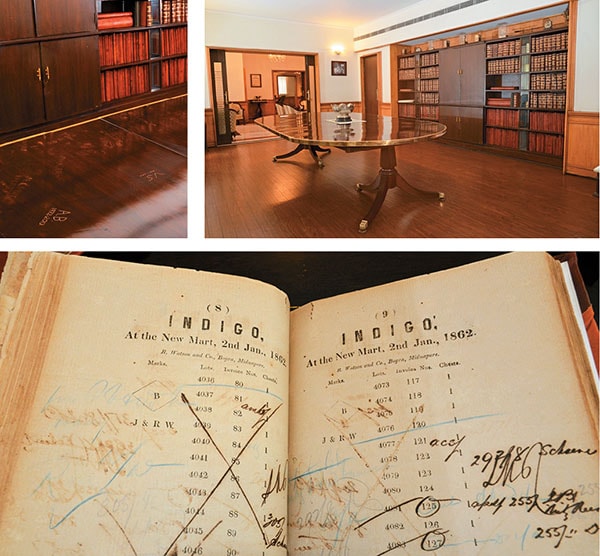

Image: Tulu Sinha

Image: Tulu Sinha

J Thomas and Company Pvt Ltd in Kolkata, established around 1840, is the world’s largest and oldest existing tea auction house. However, in its early days, it also auctioned natural indigo. At its office on Kolkata’s RN Mukherjee Road are the impeccably preserved archives of documents and records dating back to its earliest days of business, including records of indigo auctions. The oblong mahogany table, too, is a piece of history: As part of tradition, company heads etch their names or initials on this table on the day they retire. Consequently, these etchings, too, go back to the 1800s.

In response to the uprising, in which several British planters were publicly tried and executed (while some others fled), the government set up the Indigo Commission in 1860 to investigate its causes. The Minute by the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal on the Report of the Indigo Commission, which ran into more than 330 pages, began with the paragraph: “The Records of Government show that the system of Indigo manufacture in the Province of Bengal Proper has been unsound from a very early time. Whilst in other trades, all parties concerned have been bound together by the unusual commercial ties of mutual interest, in this one trade, in this one Province, the Indigo manufacturer has always been a remarkable exception to this healthy state of things.” The government then implemented the Indigo Act in 1860, according to which farmers could not be made to cultivate indigo against their will.

The Commission’s report, however, was not what rang the death knell for the cultivation of indigo in India—it was German chemist Adolf von Baeyer, who, for the first time, produced synthetic indigo in 1878. But his process was not stable enough to be commercialised. It was by 1897 that German chemical manufacturers BASF (Badische Anilin & Sodafabrik) came up with a commercially viable production process. Its immediate success can be gauged from the fact that while in 1856 production of natural indigo from India was at 19,000 tonnes, by 1914 it was down to 1,100 tonnes.

And what (almost) died along with the British indigo trade were the centuries-old traditions in the Indian sub-continent, built around the cultivation of the plant, and the extraction and use of its dye.

‘The indigo fermentation pot is like a small child,” says 57-year-old Ismail Khatri in his raspy voice over the phone from Bhuj in Gujarat. “You have to take care of it. You must ensure that it does not catch a cold, or feel hot.” He would know he is the ninth generation of his family—which came from Sindh to Gujarat in the 16th century—to dye fabrics with indigo, having worked through the rise and fall, and the rise again, of the natural dye.

Khatri, who now works with the natural dye only (which he sources from Tamil Nadu), has good reasons to: “There was a time when we worked a lot with synthetic, naphthol-based dyes, which eventually turned out to be highly toxic. My father taught us how to work with natural indigo in the 1970s, and that is what we use today.” The bladder cancer that he was diagnosed with last year was probably caused by the synthetic dyes, he believes.

But using natural dye is just one aspect of the traditional use of indigo an age-old dyeing process that does not use any artificial chemicals is the other.

“There are people who claim that they use natural indigo, but then you will see that they are not using the natural process,” says Shani Himanshu, creative director and co-founder of design label 11.11. Working primarily with khadi, the company links farmers, weavers and those working in traditional dyeing and block-printing methods. Dyeing fabrics with natural indigo in the traditional method involves a fermentation process that requires specialised knowledge, Shani says it is this knowledge that is a challenge to find.

However, for 100% Handmade brand of khadi denims, Shani claims to have found the perfect combination of the natural dye and the natural dyeing process in Jesus Ciriza Larraona, a Spaniard who revived the traditional process at his workshop in Auroville, Puducherry, and started The Colours of Nature in 1993 for producing 100 percent eco-friendly natural-dyed fabrics.

“In 1992, I was in Kashmir designing silk Persian carpets and exploring their manufacture,” he says, recalling how he came to working with indigo. “It was during this time that I became aware of the environmental impact of chemical dyes. I also realised that most of the industries in the world do not pay any attention to the environmental impact of their activities.”

In his efforts to look for natural alternatives to chemical dyes, he started working with dyers from Guledgudda, a village in the Bagalkot district of northern Karnataka. “Together we recovered the ancient natural indigo dye fermentation process which was almost forgotten,” he says.

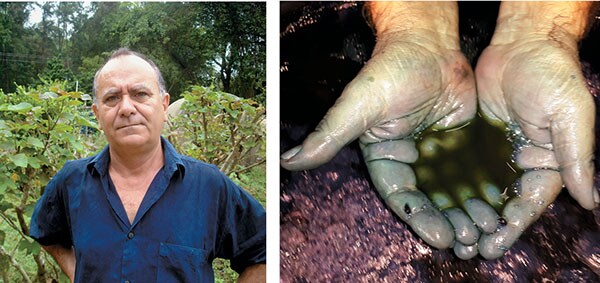

Image: Courtesy Jesus Ciriza Larraona

Image: Courtesy Jesus Ciriza Larraona

(From left) Jesus Ciriza Larraona, a Spaniard, revived the traditional dyeing process at his workshop in Auroville in Puducherry the pale green colour of the indigo solution

The most symbolic element of this process are the pots that are dug into the earth and need to be maintained at a specific temperature and alkalinity level. The fermentation process takes about a week and must be continued subsequently with fresh inputs of indigo and other ingredients, including jaggery and shell lime. Larraona started work with four 350-litre earthen pots, (“The kind used to store grains,” he says). Today, he has 30 of these pots, and 12 cement pots of 1,000 litres each. The biological process of dyeing fabric with indigo works for many years with the same dyeing water the water in some of Larraona’s pots are from 1993. “The fermentation process is the most environmentally sound process for indigo dyeing,” he says. “It consumes less water than other methods, it does not need any fixing agents and does not use the polluting chemical sodium hydrosulphite.”

Larraona’s more famous clients include Lacoste, Quicksilver and Levi’s. “After a few years of making bandanas and shirting fabrics for Levi Strauss & Co, in 2013 we manufactured denim fabric for them, using organic cotton yarns dyed by our indigo fermentation process,” he says. “We continue to work for Levi’s.”

Other designers, however, have opted for the easier and quicker dying process that involves some level of chemicals. Neeru Kumar, for instance, says that although she sources natural dyes from Andhra Pradesh and Telangana for her designs, she does not use the traditional dyeing process. Working with natural indigo, she says, requires a passion and dedication that is difficult to sustain.

Fabindia works with artisans and master craftsmen who use both natural and man-made indigo dyes. “Indigo products are sourced from a number of states, mainly Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat,” says Charu Sharma. “The process depends on the technique that is being used, and the results one is looking at. These can vary from straight forward dip-dyeing, to tie-and-dye of varying complexities, onto the 13-step process of creating complex ajrakhs. Vat dyeing using vats that have been handed down generations remains central to the process.” Employees at Larraona’s factory work with earthen pots dug into the ground where the natural indigo dye is fermented

Employees at Larraona’s factory work with earthen pots dug into the ground where the natural indigo dye is fermented

“Unlike other natural dyes such as madder, which is an acquired taste, indigo has a universal appeal,” says Shilpa Sharma, co-founder of Jaypore, an online platform for handwoven fabrics and garments Jaypore has its own label of clothing as well. “Indigo is very popular with dyeing techniques such as ajrakh, bagru and shibori.” Jaypore uses the natural dye more for block prints rather than monochrome garments since the natural unevenness of the dye is not apparent in prints. Shilpa Sharma, too, points to Telangana when asked where she sources her natural-dyed fabrics from.

And so, we head to the young state.

About 24 km east of Hyderabad is Ghatkesar, in the Rangareddy district of Telangana. In a leafy haven down a dirt road is the 3.5 acre plot of Beena and Shiv Kesav Rao, head designer and master dyer, respectively, of Creative Bee, a 20-year-old design studio that works with about 200 handloom weavers around Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. The studio produces about 10,000 metres of handloom fabrics in a year, which are variously textured, dyed and printed. Of the total output, about 40 percent is exported, 30 percent is customised and sold to clients who then retail it under their own brands, and the remaining is sold under Creative Bee’s own label.

On this plot stands Creative Bee’s dyeing and printing unit, where workers are busy hand-block printing for a recent order, a large one, from Japan. A few children sit with their school books, finishing homework, while a happy mongrel loiters around. “Indigo is a quick-reacting dye,” says Kesav, as one of his workers dips a length of white cloth, tightly bound by string (as is required in the shibori dyeing process), into a tub of indigo mixed with a reducing agent and water. Although Creative Bee does use the traditional pot for dyeing, for this demonstration they have made an exception. “The tub is usually covered to minimise exposure to oxygen, but for this demonstration we have opened it up,” he adds.

The colour of the solution, pale green, transfers onto the cloth in about 15 minutes, when it is pulled out, untied and held out by three or four people to dry. As the dye comes in contact with air, it gets oxidised and begins to change colour—from pale green to a dark blue. “The point at which you remove the cloth from the dye is crucial,” says Kesav. “Remove it too early, and the colour will run remove it too late, and the colour will run again.” As the length of cloth begins to dry, the patterns created by the binding strings become increasingly prominent. The darker the shade of blue, the more number of times is the fabric dipped in the dye (sometimes up to 40 times).

Creative Bee sources its dyes from Tindivanam, a village in Tamil Nadu. “We earlier also sourced from Kadapa in Andhra Pradesh. But those growers have abandoned indigo cultivation and have now become real estate developers,” says Kesav with a wry smile. “I am to blame,” rues Beena, recalling how she had introduced the Kadapa growers—the only farm in the region growing natural indigo—to a foreign buyer. After getting a lucrative order from this buyer, the growers decided to give up farming altogether.

The effect that the closure of one farm can have can be understood from the fact that there are very few people who still grow the indigo plant. “One crop can give, at most, two harvests the third harvest is for the seeds,” says Kesav. “But usually it is just one harvest. The quality of the leaves, from which the dye is extracted, is dependent on rain and soil conditions.” He adds that the dye is still cultivated largely in Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Tamil Nadu with perhaps smaller quantities in Bihar and West Bengal. “The British practice was one of the major reasons why people stopped cultivating indigo in most places,” he says. “And then, of course, was the advent of synthetic indigo.”

Apart from a general shortage of the natural dye, there is also the concern of adulteration. “If we trust our supplier, we can ask them to send the dye as a powder it is easier for us to dissolve it,” says Kesav. “But if we don’t trust them, we ask for the dye in the form of cakes because then they can’t mix adulterations, such as sawdust, which they can mix in the powder form of the dye.” On an average, it takes about 100 kg to 150 kg of natural indigo (it costs about Rs 2,200 per kg) to dye 3,000 to 5,000 metres of fabric printed fabrics require a smaller quantity of the dye than fully dyed fabrics.  (From left) The 100% Handmade brand of khadi denims produced by 11.11 combines natural dyes with the natural dyeing process some products from Fabindia’s indigo collection. The brand launches a new collection every year

(From left) The 100% Handmade brand of khadi denims produced by 11.11 combines natural dyes with the natural dyeing process some products from Fabindia’s indigo collection. The brand launches a new collection every year

Like all other natural vegetable dyes, the extraction of indigo is a time- and labour-intensive process. And one, believes Kesav, that has immense potential in India. However, commercial levels of production of any dye require investments of time and money and a waiting period, since the returns are usually long term.

He explains this through the example of the natural olive green dye, which is produced from dry pomegranate rinds. “The rind is actually a waste product of the juice industry,” he says, “but we buy it for Rs 60 to Rs 70 a kg. If there is one company or organisation that invests in the process, this is how it can be managed: A farmer could be growing the fruit, which would be used for making juice the rind would then be dried and be made into dye the waste product of the dye could then be used to make biomass and also as fertiliser in the orchards. It comes a full circle.”

In the case of indigo, Kesav believes that large companies that produce industrial quantities and qualities of dyes could adopt villages where they support farmers in the growing and manufacturing of indigo, and then use the dye in the processing of mass produced clothing such as denims.

Indigo, the colour, may have caught the country’s, if not the world’s, imagination in the past few years. But whether a centuries-old tradition will fade into history, or will survive in the way stubborn habits do, is something that is yet to be seen.

First Published: Aug 13, 2016, 06:59

Subscribe Now