Hemingway's Cuban affair

Havana is still as much in love with the Nobel Laureate, as the writer was with it

The roads of Havana are teeming with gleaming models of old cars, which have been plying at least since 1962, from the time of an American embargo that stopped the Cubans from importing cars or spare parts

The roads of Havana are teeming with gleaming models of old cars, which have been plying at least since 1962, from the time of an American embargo that stopped the Cubans from importing cars or spare parts

Image: Javier Gonzalez Leyva/Shutterstock

The view from the rooftop bar at Hotel Ambos Mundos is magnificent, stretching all the way up to the harbour on one side, and spanning the old town on the other. Several tables are occupied with tourists sipping on chilled Mojitos and Daiquiris. A local band is kicking up a storm, even at that early hour before lunch. But, then, this is Cuba, and music is in the very air that this small island breathes.

Most of these tourists are here to pay homage to Ernest Hemingway, that brilliant and capricious writer whose fondness for Cuba brought him back to the island again and again. And it is in this very hotel that he stayed for about seven years—from 1932 to 1939—while finishing Death in the Afternoon and beginning For Whom the Bell Tolls.

Located in the heart of the old quarters, on the intersection of what is now one of the most popular streets for tourists, the Calle del Obispo (Bishop Street) and Calle Mercaderes (Merchants’ Street), Ambos Mundos was built in 1924. It was a time of prosperity in Havana, much of it funded by US interests using the island as a base for contraband. It is said that Hemingway first discovered Cuba on his sea voyage to Spain in 1928, and fell for the laidback charms of both the place and the people.

He took up residence in Room 511, now maintained as a shrine to his work, containing his writing desk and typewriter, among other things. It is shut for maintenance work when I drop by, but I am happy to just walk around the foyer and admire the old photographs of this genius. The crabby old bellhop escorts me to the rooftop restaurant with great reluctance I am not a guest at the hotel, so why oblige me, he seems to think. But on the way up in the rickety elevator of the same vintage as the hotel itself, he opens up a tiny bit. He volunteers the information (in Spanish, to my Cuban friend) that Hemingway’s room had similar expansive views as the terrace, so he thinks my trip was not completely wasted. La Bodeguita del Medio, which Hemingway is known to have frequented for a few Mojitos

La Bodeguita del Medio, which Hemingway is known to have frequented for a few Mojitos

Image: Shutterstock

The name Ambos Mundos translates roughly to ‘two worlds’, and in the few days I spent in Havana, I come to realise this term could be used to describe the city itself. Havana is clearly a city of dire contrasts: Decrepit in parts and glitzy in others, torn between the crushing weight of its past and the glimmering promise of its future.

Ever since Christopher Columbus claimed this island for Spain in 1492, there have been the occasional prosperous and peaceful phases, punctuated regularly by political and social tumult. This reached a crescendo in 1959, after Fidel Castro and his gang of rebels (or freedom fighters, as some would call it) overthrew President Batista and declared communist regime over the country, alienating the USA and befriending the USSR. Things went rapidly downhill after the fall of the USSR in 1991, when Cuba suddenly found itself friendless and isolated. With former US President Barack Obama’s visit in the last few months of his term, and his overtures to ease restrictions on travel and trade, things have begun to look up (although current President Donald Trump has undone much of that).

As I walk out of Ambos Mundos into the warm sunshine, I can see many American visitors thronging the bar right next door, vying for selfies that take in as much of the crowded room as possible. The La Bodeguita del Medio, one of the bars that kept Hemingway’s creative juices alive, is where he was known to down several Mojitos at a go. His drink even came to be called the Papa Doble, with no sugar and twice the normal amount of rum. And as with many other places the writer frequented, this bar also proudly milks the connection for all it is worth, inviting tourists to drink where the writer did. But I have been warned that the Mojitos in other bars taste much better and cost much less, so I walk past after a cursory glance.

My guide Nelson Albuquerque is waiting to take me on a drive in a classic 1950s American convertible. These shiny cars are all over Cuba, one more piece of the puzzle that has remained frozen in time. At least, ever since 1962, when the American embargo meant that Cuba could not import new cars or even spare parts, forcing them to maintain what they already had in pristine condition. Therefore, the gleaming Buicks and Oldsmobiles, Chevrolets and Plymouths in bright colours ply on Cuba’s roads.  Finca Vigia, where the writer lived with his third wife

Finca Vigia, where the writer lived with his third wife

Image: Shutterstock

My chariot for the afternoon is a red and white Ford Fairlane, that driver José had polished to near perfection. He is also very possessive about this piece of machinery and asks me to open and shut the door as gently as possible. As for Nelson, he is a retired English professor who shares my love for Hemingway. Right away, we both agree that he was a great writer, but his personal life left much to be desired, especially his treatment of his wives and mistresses, which included verbal and physical abuse.

After all, several critics have argued that Hemingway’s alcoholism and multiple affairs are enough to disqualify him from a place in any list of great authors, not to forget his harsh portrayal of some of his women characters. However, a greater number of both readers and writers would agree that his contribution to literature is remarkable, not limited just to his eye for stories of conflict (both internal and external) and flair for pithy sentences (perhaps an extension of his overarching masculine persona). Nonetheless, Hemingway’s work fascinated both Nelson and me deeply him enough to lead eager literature lovers as myself on the Hemingway trail in and around Havana.

We make our way out of Havana towards the small hamlet of San Francisco de Paula, half an hour away. In 1940, Hemingway finally put down roots in Cuba, along with his third wife Martha Gellhorn (herself an accomplished journalist and war correspondent), in the form of a house. The couple called the sprawling home Finca Vigia, or lookout point, an apt name given its location on a low hill, overlooking lush vegetation and the sprawl of the city in the distance. It is from this house that Hemingway wrote two of his most famous novels, For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea.

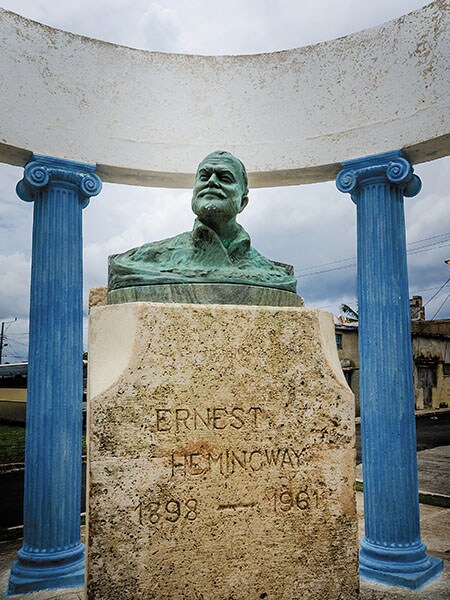

Cuba turned Hemingway into a son of the soil, or rather, in his case, the sea. He went fishing on his boat Pilar every day hung out with the Cubans drank at local bars dry and invited rich and famous friends from the USA for lavish parties. The house, recently converted into a museum, is a shrine to Hemingway and his love for Cuba and its people. Nelson says that it is almost exactly as Hemingway would have left it in 1960 indeed, there are several moments when it feels like he never left at all. And this is not as far-fetched as it seems. When the Hemingways (by that time, he was on to his fourth wife, Mary Welsh) left Cuba in 1960, it was to be a short journey, to attend to some personal business in the US. But he committed suicide the following year, at the age of 61, bringing the Cuba story to an abrupt end. Hemingway’s bust in the fishing village of Cojimar

Hemingway’s bust in the fishing village of Cojimar

Image: Shutterstock

It is a stylish, single-storeyed bungalow, originally built in 1886, and painted in a pastel cream colour. The interiors of the house are off limits to visitors—that is how the government prefers to preserve it—but the windows and doors are wide open for us to peek through. Every room contains Hemingway’s personal artefacts: From unfinished manuscripts and old newspaper clippings in the library, to overlarge chintz-covered armchairs, and the hunting trophies mounted on the living room walls.

“His presence is palpable in this home,” says Nelson, as we walk towards the swimming pool where actress Ava Gardner once (supposedly) swam in the nude. Right next to the dry pool is his fishing boat Pilar, almost exactly as it was when he used it.

Pilar plays a dominant role in Hemingway’s life as a Cuban native. Along with his friend captain Gregorio Fuentes, he spent long days and nights at sea, sailing and fishing. This love for the sea led him to be a frequent visitor to the nearby fishing village of Cojimar, where he would dock. This village was the inspiration for his 1953 Pulitzer-winning book The Old Man and the Sea. In fact, it is believed that Fuentes (to whom he left Pilar) was the person upon whom the character of Santiago, the book’s ‘old man’, was based.

Cojimar, where we head to next, turns out to be my favourite among all of Hemingway’s haunts. In this tiny village, with its narrow lanes lined with colourful homes, time seems to have stopped. The sun is high up in the sky and most of the residents are inside their homes, ready for their siestas. At the La Terraza bar, referred to in the book as The Terrace, there are dozens of Hemingway photographs on the walls, including rare ones of the writer with Fidel Castro. And in one corner of the inner room, there is a table set by the window—this one has the best view of the water—ready for Hemingway’s meal. Like other places he frequented, this bar too is a tribute to the man who seemed to have won over Cuban hearts completely.

From the bar, we walk towards the ruins of the Torreon de Cojimar fort, right by the sea. Nelson says that on a clear day, it is possible to see all the way to the American coast. Whether this is reality or fantasy, I am not sure, but the views from this spot are certainly spectacular. There is a bust of Hemingway here, the inscription reading: “Sculpted with the contributions of the fishermen cooperative of Cojimar”. In 1961, soon after Hemingway’s suicide, the fishermen of Cojimar—to whom he dedicated his Nobel Prize that he won in 1954—decided to erect a memorial to mark his relationship with them and their hamlet. So, they melted down small fittings from their boats to provide the bronze for this statue, which still stands looking out on to the sea.

First Published: Dec 01, 2018, 08:32

Subscribe Now