Art & Architecture: The Treasures of Marwariland

The Marwaris trace their descent to a small pocket of Rajasthan, a state with an opulent tradition of art and architecture

The Marwaris have little to do with Marwar (or Jodhpur, as most people know the capital) in spite of the moniker they bear with such pride they were originally from the Shekhawati region: Small towns in a triangle that lay between Delhi, Jaipur and Bikaner. (Ironically, there they weren’t known as Shekhawats, that nomenclature being claimed by the Rajputs.) They flourished as businessmen with an acute sense of enterprise, making money from the satta markets and stock exchanges of cities and countries far from their own.

The name was earned because a few ingenious grandees from the business families of Shekhawati marched with the army of the maharaja of Jodhpur (or Marwar, as it was known) to Calcutta. These innovative businessmen, who kept the infantry supplied with uniforms, boots, rations and horses, soon earned the sobriquet ‘Marwaris’, a term the British used when looking to appoint business suppliers who kept them fed and watered, and managed the local trade that the East India Company needed to flourish in what would become the outpost of the Empire. It was in Calcutta that the Marwaris made their biggest fortunes—RK Dalmia becoming the ‘silver king’ for hoarding the metal at the height of the war years in Europe.

The Marwaris spotted the opportunity that was offered to them on the silver salver emblazoned with the emblem of the Windsor crown: There was business to be done, money to be made, and they made it, sending the wealth back to the dusty desert, to build homes to rival the mansions of the elite in the cities.

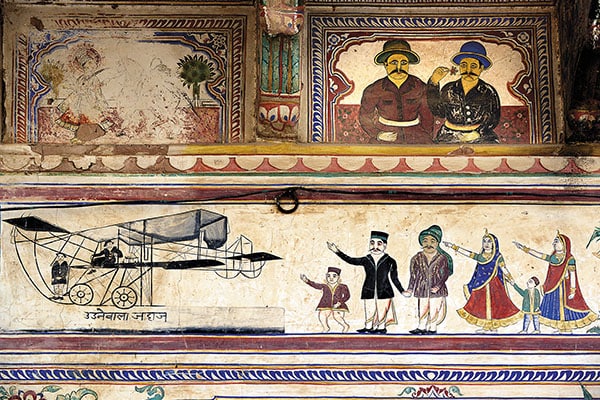

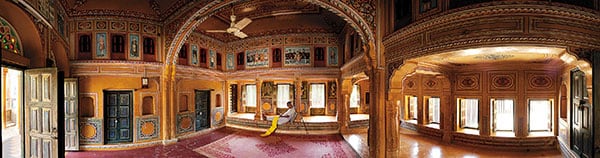

The havelis of Shekhawati were created to house large joint families. They had one courtyard, or two, or four. Fresco painters were commissioned to embellish interiors and facades with mythological and, occasionally, historical episodes.

Later, their patrons asked them to illustrate more modern wonders: Trains and aeroplanes, gramophones and telephones (the artists, who had never seen these creations, painted them from imagination). Because the gods needed their transport, they painted Ram and Sita being chauffeured by Hanuman in luxury cars instead of chariots. Eventually, the merchants decided that there was little to be gained from living in the provinces they summoned their wives and children to Calcutta and Bombay and Surat, and the havelis went into decline, abandoned, locked up, divided and sub-divided between families till only caretakers were left to manage their tattered glory.

The ‘world’s largest open-air art gallery’ might have gently faded, but for two city-slickers who backpacked their way through its alleys, exploring the fascinating frescos, demanding that locked mansions be opened and chambers be shown to them. They authored a book that celebrated the art of the Marwaris and opened the doors to ‘heritage’ tourism. Francis Wacziarg and Aman Nath might only have attempted to document the heritage they had chanced upon, but of it was born a legacy that led the families of Rajputs—not the Marwaris, let it be clarified—to reclaim the rich heritage of, well, all of Marwariland. And what a rich and astonishing legacy it has been.

Forts and temples, palaces and mansions, murals and frescos, inlay and pietra-dura. Architecture that is Rajput, Mughal, British, Indo-Saracenic, Art-Deco, Gothic, Elizabethan, Edwardian, with interiors enhanced with gold, painted, chandeliered, carpeted, styled into Indian zenanas and European salons, with private lakes (Udaipur) and railways (most kingdoms had their own), aircraft (Jodhpur’s maharaja died in an air crash the day he won independent India’s first elections Bikaner’s Karni Singh piloted his own aeroplane, and rare bombers are part of its museum Udaipur’s Arvind Singh still flies his own aircraft) and polo teams (Jaipur demanding and getting what was considered the world’s finest team, the Jodhpurs, in dowry). It was an exciting, eclectic, creative hothouse and, amazingly, much of that heritage is still thriving.

In 1901, when Maharaja Ganga Singh moved into his Lallgarh palace from the nearby Junagadh Fort, it was probably the grandest residence in Rajputana, built entirely of red sandstone. By the time Jodhpur’s royal head commissioned Umaid Bhawan Palace—as a famine relief project!—ambitions had soared so high, it took the audacity of Sir Edward Lancaster to take on the might of Edwin Lutyens’s Viceregal Lodge in New Delhi some might say it is the greater triumph even though it is more Hollywood set than Indian palace. A few years later, Maharaja Man Singh of Jaipur would bring home his third bride, the breathtakingly beautiful Ayesha—or, as she came to be known by an adoring public, Gayatri Devi—and stylists were flown in from London to make Rambagh Palace fit, truly, for a princess: Its ceilings painted with scenes of Renaissance art. Image: Amit Pasricha

Image: Amit Pasricha

Frescoes frequently portrayed modern themes in traditional styles

But enough of palaces and pomp. Bikaner’s Maharaja Sardar Singh had his portrait painted in his Badal Mahal where, in the middle of the desert, a painter covered the walls entirely with mirages of cooling rainclouds. His portraitist was from Turkey, merely passing by, as was Stefan Norblin, the Polish master who chanced upon Jodhpur and accepted a commission to paint murals in the master suites for the maharaja and maharani: Heroic scenes from the Ramayana in a Nordic tradition, only recently restored by the Polish government. Udaipur’s maharana commissioned Raja Ravi Varma to paint portraits of Rana Pratap and Maharana Fateh Singh, both extant in the bar of Shiv Niwas Palace. The Jaipurs chose Europeans to paint scenes on the ceilings of their palaces and walls, but also the Indian artist SG Thakar Singh. In Bikaner, Herman Mueller was assigned to make paintings of historic episodes.

But this was later. Earlier, the Rajputs built forbidding forts but, being as much aesthetes as warriors, they decorated them lavishly. In Kotah and Bundi and Karauli, they painted them with scenes of battles and of shikar (and, if you peeped into their boudoirs, of erotic dalliances too). In Kishangarh, an artist created an extraordinary body of paintings of Radha, the images becoming representative of the high art of the state. The maharajas of Jaipur, Udaipur and Bikaner commissioned the ateliers to create an evocative series of miniatures, illustrating the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, the court painters spending their energy on painting the Ragamala and the Baramasa or 12 seasons. In Jaipur, the maharaja who broke convention to cross the kaalaa paani to go to London, carried with him holy water from the Ganga in giant pitchers, the largest silver objects in the world.

Once they started travelling overseas, there was no holding back the potentates. They brought back European treasures. The maharana of Udaipur ordered a palace full of Osler crystal furniture, now on view in a gallery of the City Palace. The Jodhpurs ordered all the furniture for Umaid Bhawan from London. (As ill-luck would have it, the manufacturer’s factory burned down, then a second order shipped by sea was bombed—these were the War years. So, finally, local carpenters recreated the Art-Deco furniture. Today, Jodhpur is a major centre for the manufacture of colonial and made-as-old furniture.) They also ordered Wedgwood, Bohemian crystal, Rosenthal tableware and dinner services. The maharanis wore Mughal jewellery created by artisans in Bikaner and Jaipur—24k gold and uncut diamonds, with enamel work on the reverse—and also ordered from Cartier and Van, Cleef & Arpels.

Udaipur palace’s Mor Chowk was embellished with almost as much care as they took for their jewellery, the enamel work laid by Italians still glittering. Jaipur’s seven-tiered palace, built in the traditional style but with a keen Western sensibility, had Lalique dining tables. Hunting lodges and billiards rooms were mounted with trophies of hunts not just in India but also in Africa. Jaisalmer’s maharawals, who commanded critical trading routes and amassed huge wealth, spent it creating palaces of red sandstone, carved into lattice screens of such delicacy they resembled lace.

But the ambitious prime ministers of Jaisalmer were even richer than the rulers, and their vaulting aspirations, perhaps for the first time, over-reached themselves in ordering havelis the likes of which even the maharawals did not imagine. These were Jains, also shrewd businessmen, and they built temples and havelis.

The Marwaris were altogether different. They were confident of their wealth and did not need to flaunt it. So they did with it what is now regarded as corporate philanthropy each, and in stages, contributed to their villages and towns—first in Shekhawati, then in the kingdoms of Rajputana, and, later, in the many cities of their residence—a temple, a well, a sarai (resting places for travellers), and a school.

Having given to society, the well-knit community ensured their living space was comfortable but never ostentatious, laying mattresses on carpets and covering them with spotless white sheets on which they conducted business. The lavish Mittal weddings in Paris and Barcelona are something the community would earlier have frowned at rather than celebrate with such pomp.

When they went overboard, it was in the temples. Well, okay, blame it on the grandiose Jains again, who ordered the stonemasons to carve marble columns like rare sculptures, each one exquisite, so when you see them in the hundreds, it creates a feast of excess. Such rare and pure beauty are to be seen in Ranakpur and Dilwara in south Rajasthan, and in Palitana’s Mount Girnar just across the border in today’s Gujarat.

Both Marwaris and Rajputs commissioned sculptors and painters to create relief panels to embellish temples. In Nathdwara, the pichwais (curtains) that concealed a jhanki of Krishna became celebrated for the quality of their paintings, turning into religious souvenirs before becoming collectibles. In Pushkar’s fair, even the camels’ coats were cut into patterns of almost abstract design.

Perhaps it was in their nature, this need to decorate, whether their footwear embroidered in furious colours, or their swords and daggers, which they set in gold and encrusted with gemstones. Printers and weavers lent vibrancy to their veils, skirts and turbans. Colour, lacking in the environment, blazed in their raiments.

The miniature artists of Jaipur and Udaipur still churn out fine copies of what their ancestors rendered centuries ago. In Shekhawati, some of the old havelis have been rescued. Businessman Kamal Morarka has restored his haveli in Nawalgarh, the frescos fresh and bright once more. In Mandawa and Dundlod, tourists find a still-flourishing culture. In Mehrangarh, the ramparts host parties for the world’s rich and famous. In Udaipur, the head of the dynasty has an archival house documenting, digitising and restoring old photographs, displaying a curated selection in a gallery, showing that the ability to preserve family legacies is keen. Jodhpur’s polo events are a big draw, and the family has managed to restore parts of the impressive Mehrangarh fort as well as that in Nagaur, where a baron maharaja once ordered gardens and pools in what centuries ago must have been akin to today’s luxury spas. In Japiur araish artists, who lend a marbled effect to painted walls with treatments of lime and eggshells, have resurfaced to decorate homes, havelis, heritage hotels and shops. To see what they achieved, go no further than Samode, where the prime minister of the house of Amber recreated a crenellated retreat with painted walls that combined the skill of the Shekhawati fresco artist with the muralist of Jaipur. Jodhpur and Shekhawati are known for their ‘country look’ furniture.

The bazaars of Jaipur are the largest handicrafts centre of the world designers pour in to order yards of block-printed fabrics, carpets and dhurries, blue pottery, silver embellishments and jewellery. The city is where the bulk of the world’s rough gemstones—rubies, emeralds, amethysts and sapphires among them—arrive to be cut. They are then sent back, but also auctioned to bidders who use these to recreate legacy jewellery with ropes of diamonds impossibly large sets that recreate another age, when such beauty was not to be quibbled at.

The Marwaris were patrons, of course, but they are also peddlers of these astonishing treasures. No wonder that the most obvious trade in the pink city remains the buying and selling of these rare pieces of ornamentation. In a city painted pink to commemorate a royal visit, this is really no surprise.

Marwariland’s celebration of art and craft is alive and well.

First Published: Mar 22, 2014, 06:48

Subscribe Now