A journey to the end of the world: The Arctic Sea's Wrangel Island

Wrangel Island, in the distant and isolated Arctic Sea, is cold and stark. But it's a hotspot for several wildlife species, including the mighty polar bear

The strongly built man, with a neatly trimmed beard, introduces himself simply as “Nikita Ovsyanikov, polar bear biologist”. We meet on the Spirit of Enderby, where Nikita, who is one of the world’s leading experts on polar bears, is part of a team of naturalists on our expedition in Russia’s Far East, to Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean. He also happens to be one of the reasons why I am on the vessel my desire to visit Wrangel being partly fuelled by reading his articles and books.

It is a happy coincidence that Nikita should be on the same ship.

The roundtrip from Anadyr, the capital of the Chukotka region in Russia’s farthest northeast corner, to Wrangel Island will take around two weeks on Professor Khromov, an old, ice-strengthened research vessel that has been converted into an expedition vessel, now called the Spirit of Enderby, for Arctic eco-tourism operated by Heritage Expedition. The 50 passengers on board are from Australia, New Zealand, America and Europe, and include a German film crew working on a production that traces a 19th century research expedition of naturalist Adelbert von Chamisso.

Anadyr’s remoteness makes it difficult to reach: Passengers arrive on a special charter from Nome in Alaska, across the Bering Strait, or on the weekly long-haul flight from Moscow.

â‹ â‹ â‹

Wrangel Island (Ostrov Vrangelya in Russian) was known to the native Chukchi people. However, between 1820 and 1824, German explorer Baron Ferdinand von Wrangel led an expedition, in search of the island, based on historical reports and indigenous Chukchi stories. The definitive discoverer of the island is disputed, and although Wrangel never actually found it, another contender, an American whaling captain called Thomas Long, curiously named it after him.

The 7,600 sq km island, between the Chukchi Sea and East Siberian Sea, is some 140 km off the coast. It was neither glaciated, nor submerged by rising sea levels, and thus is unique in that the biome has evolved largely uninterrupted for millions of years.

Wrangel Island, as well as the nearby Herald Island and its surrounding waters, are a federally protected zapovednik, a nature reserve where most human activities, other than those for scientific purposes, are prohibited. Four rangers live on the island all year round, and are supplemented by a few researchers. The 150 to 200 tourists who visit each year need special permits before arrival.

Wrangel Island is accessible by sea only in July and August. The climate is forbidding: Temperatures fall to -40°C to -50°C during lengthy winters, when high winds and snowstorms are common. Summer is around a month long, when temperatures rise to around 0°C. The weather we encounter is variable: Some days are gloriously sun-lit, while others are misty and foggy. Strong northern winds and rough seas prevent us from visiting the exposed north side. Irrespective of weather conditions, the rugged coastline, hills and the tree-less Tundra are starkly beautiful. The light, clarity and brilliance of the vast, often seemingly endless, landscape are extraordinary and sometimes overwhelming. What adds to this sense of isolation is the lack of human habitation.

Our journey hugs the Russian coastline, making it possible to visit locations of historic and natural interest. One such stop is Yttygran Island, an ancient site commonly known as ‘Whale Bone Alley’, which dates back many centuries, and derives it name from the huge whale jawbones that stretch in a line for nearly 500 metres. It is thought that these bones were markers for boats, or served a supportive function for storage or working purposes to the several tribes of indigenous people who used boats (called baidaras) made of walrus skin. Although it is not known how many whale jawbones were initially installed, only seven of them remain standing.

Another one of our stops is Cape Dezhnev, the easternmost mainland point of Eurasia, named after Semyon Dezhnev, the first recorded European to round its tip. The cape is a barren tip of a high, rocky headland, consisting of little more than a lighthouse, an abandoned village and a monument to Dezhnev himself. We also visit Kolyuchin Island, the site of a now-defunct meteorological station, and Belyaka Spit at Kolyuchin Inlet, all noted wildlife spots.

In the Bering Sea, between Siberia and Alaska, we pass Ratmanov Island (also known as the Big Diomede Island), the easternmost point of Russia. From here, on a bright and clear day, it is possible to see Alaska (perhaps even Sarah Palin!). A short distance away is the US’s Little Diomede Island. And in between the two islands passes the International Date Line, giving you the opportunity to look into both the past and the future.

The time we spend out at sea is filled with lectures from the naturalists. Some hardy souls spend most of the almost-24 hours of daylight out on the vessel’s bow deck or bridge, keeping a lookout for birds and mammals. On most days, there are shore visits, using the ship’s five zodiacs (small inflatable boats used by the military). Walkers hike over the Tundra botanists explore plant life wildlife enthusiasts search out avian and mammalian life.

At Uelen village, located on the mainland near Cape Dezhnev, where the Bering Sea meets the Chukchi Sea, we visit the local Chukchi community while being watched by Russian border guards. Uelen, which has a population of just about 700, is the country’s closest point to the US.

With a history that is believed to go back 2,000 years, the Chukchi are people who live off sea mammals. Drying meats, skins and animals’ parts are clearly visible in windows and on drying racks. Uelen is known for ivory carvings (from the bones, teeth and tusks of whales, walruses and seals). The village even has a museum dedicated entirely to this art. For itinerant tourists, there are mementos that can be bought at the museum. When we visit, dancers from the Chukchi community put on a performance for the tourists, who, in turn, join by shaking a leg.

â‹ â‹ â‹

For a landscape that is very cold and stark, the region’s plant life is diverse and unique: Of the 400 species of plants found in the Russian Far East, around 20 are not found anywhere else. However, this botanic world is in miniature and researchers and enthusiasts are seen in a supine position, large magnifying glass in hand, studying their subjects.

In places, you will find entire stretches covered in the blue monkshood flower. Because of the time of our visit, we come across flowers such as the tiny crowberry, the delicate cloudberry, the speckled saxifrage, the elongated horsetail, the blue-and-yellow forget-me-nots and cotton grass that are still in bloom. And even if you don’t come across blossoms, there is moss and lichens almost everywhere.

Most plants here are resistant to freezing, which makes them capable of withstanding extreme weather conditions. They have also devised their own survival mechanisms, which include growing in clumps (called ‘cushions’), or covering their stems with hair that traps heat, allowing the plant to maintain its temperature several degrees higher than the surrounding air others have large tap roots so that 95 percent of the plant’s biomass is underground.

The birdlife, comprising primarily seabirds, is limited to a few species, many of which are annual migrants that travel to the Arctic regions in the short summer to breed. Some of these occur in prodigious numbers, and despite the fewer number of species they make for excellent viewing. For instance, at one point in our sea journey, the ship is surrounded by hundreds of thousands of short-tailed shearwaters.

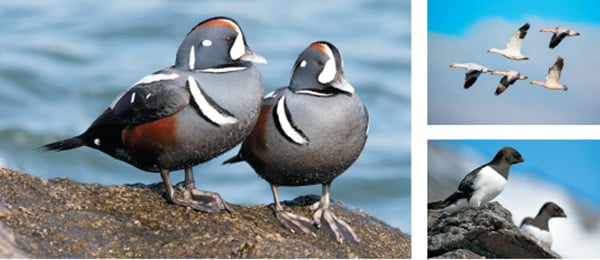

Seagulls such as the black-legged kittiwakes, the glaucous and vega gulls, and the shearwaters, the northern fulmars and the phalaropes are abundant. There are various eider and harlequin ducks, although most are in their dull eclipse plumage, as they are moulting after the breeding season.

The major attraction, however, are the auks or alcids, the northern equivalent of penguins. Although their short wings make them clumsy fliers, they are excellent swimmers and divers. They hunt by using a technique called pursuit diving where they literally fly underwater to chase small fish. The birds are restricted to cold waters, as this style of chasing prey becomes inefficient in warmer waters where the fish are larger. Consequently, the Northern Pacific is home to around 20 species of alcids.

Generally found in the open sea, these birds come ashore in summer, nesting in large colonies in often inhospitable cliffs and sea stacks. One peculiarity of some alcids is the shape of their eggs, which are not oval but narrow and pointed at one end, preventing them from accidentally rolling off their precarious nests.

Flocks of snow geese fly overhead in their familiar ‘V’ formations. Wrangel Island is the only surviving snow goose colony in Asia, with an estimated 60,000 nests. On Belyaka Spit, we come across a small group of emperor geese, as well as yellow-billed and Pacific loons (also known as divers).

We get to see peregrine falcons, the Arctic variety being among the largest in the world. The bird is capable of attaining truly impressive speeds of up to 220 mph while on a dive, and is known to capture prey mid-air. We see them on the hunt for small birds on more than one occasion.

One of the highlights of the avian population in the region is the snowy owl, for whom Wrangel Island is an important nesting area. Native to Arctic regions, the yellow-eyed, black-beaked owls are large—around 60 to 70 cm tall, with a wingspan of 1.2 to 1.5 metres, and weighing between 1.5 and 3 kg. The males are all white, while the females and the fledglings are similar with darker grey markings. Near the rangers’ camp, Irina, Nikita’s wife who is on the island researching the owls, takes us to see a pair and a chick at close quarters. While walking on the Tundra, we see a few of the owls hunting and listen to their mewling calls.

â‹ â‹ â‹

The central attraction of our voyage is, undoubtedly, the polar bear, standing over 1.3 metres at the shoulder and up to 3 metres in length. The large males can weigh up to 700 kg, with the females weighing about half of that. The bears are classified as a marine mammal (the scientific name Ursus Maritimus meaning ‘maritime bears’). Polar bears occupy a narrow evolutionary niche: Their heavily insulated bodies are adapted for extreme cold, and travel across ice and expanses of ocean. Born on land, they spend most of their time on sea ice, using it as a platform to hunt seals, their preferred prey.

On the southern side of Wrangel Island, Nikita spots a number of polar bears feeding on a washed-up carcass of a whale, and we immediately take to the zodiacs to make the most of this rare sighting. The bears, 14 or 15 of them, are of varying age and size. At the kill, they are interacting in a communal way, unusual for animals usually regarded as solitary creatures. While some eat, others rest, or await their turn at the food. Most have full bellies, with their faces streaked with blood and blubber. Nearby, we see a female with a cub. Two males get into a mock fight, lit up briefly by a shaft of glowing sunlight.

Although the water is choppy, we manage to approach the bears from the downwind direction, which lets us get within 10 metres of them. But a large male notices us and walks to the edge of the surf to investigate, forcing us to quickly withdraw. Over the days, we see more bears, but usually at a distance on the Tundra. The more adventurous among us were treated to cold and wet zodiac rides along the coast by Nikita and another crew member for closer encounters with around 14 more bears.

But Nikita’s concern is palpable in our chats. He has spent more than 30 years researching polar bears on Wrangel Island. When he and his wife, Irina, had spent time on Herald Island in the 1990s, they had recorded the highest concentration of polar bear dens ever found in the world: 12 dens per square kilometre. The steep cliffs, with their terraced tops and proximity to the sea and surrounding sea ice, was ideal for the animals to hunt, and for the females to come to the island to their dens.

Today, the warming climate and shrinking ice has resulted in fewer females denning on Herald Island. By autumn, when they would normally come ashore, the ice has retreated too far from land for them to conveniently reach it. Recent research records show only around 30 maternity dens on Wrangel and Herald islands, a 90 percent fall from the 300 recorded in the past.

Polar bears are built to hunt on the edge of sea ice, living off fat reserves when food is absent. Global warming has meant reductions in the level of sea ice and longer ice-free periods. Fewer cubs now survive and adults regularly appear to be underfed and stressed.

The bears are highly adaptable, having evolved over hundreds of thousands of years, during which large scale climatic events have occurred. But, in present times, their ability to adjust is restricted by man-made conditions such as pollution, disturbance and increased man-animal conflicts. As if to underline the issues, on our return to Anadyr, we learn of a bear that was shot when it came into contact with people.

These magnificent creatures are likely to disappear within 20 to 25 years. Scientific, environmental and political groups bicker and strike bizarre deals that allow hunting to continue but do little to preserve this iconic species.

â‹ â‹ â‹

As we sail away, Wrangel Island is bathed in bright sunlight. Lenticular clouds, a series of ascending spirals resembling a UFO, hover in the piercing blue sky. There is snow on the distant hills. On the rear deck of Spirit of Enderby, I catch a glimpse of Nikita, standing silently, looking at the receding island where he has spent so much of his life.

Nikita has lived among the bears to understand them, observing their behaviour over long periods of time. He has tried to change people’s ways of thinking about these magnificent animals, which are intelligent and curious, but cautious. Under his leadership, no one carries a gun on Wrangel Island, and no bear or human has been killed despite almost constant encounters. In contrast, in Norway’s Svalbard, where everyone is required to a carry a gun, many polar bears and several people have been killed.

He appears lost in thought. I wonder how long his beloved island and its bears will last. I want this incomparable Arctic wilderness and its wildlife to survive intact. But I know it is a forlorn hope.

Satyajit Das is a former banker and the author of The Age of Stagnation. His previous books include Traders Guns & Money and Extreme Money. He is also the co-author with Jade Novakovic of In Search of the Pangolin: The Accidental Eco-Tourist

First Published: Sep 24, 2016, 06:44

Subscribe Now