The Battle For U.P.

How the outcome of the UP elections could influence the course of India's economic reforms

I

Perhaps that is the reason why India’s beleaguered economist-Prime Minister Manmohan Singh gave an unusually stern message to industry leaders, asking them to pipe down the ever increasing voices of discontent against his government “until March [2012].” This was in the third week of December, just days before elections were declared in five states—electorally amounting to almost one-fourth of India.

For the better part of the past two years, Singh has failed to push the economic reforms agenda. It is the toughest phase for him since even his core constituency—industry leaders, people who actualised Singh’s policies and posted the now enviable growth figures—have turned hostile. Inability to enact reforms in the retail, pension and insurance sectors among others, has robbed Singh of his only support base. The curt message along with the promise to deliver results after the state polls looked more like the last roll of the dice by Singh.

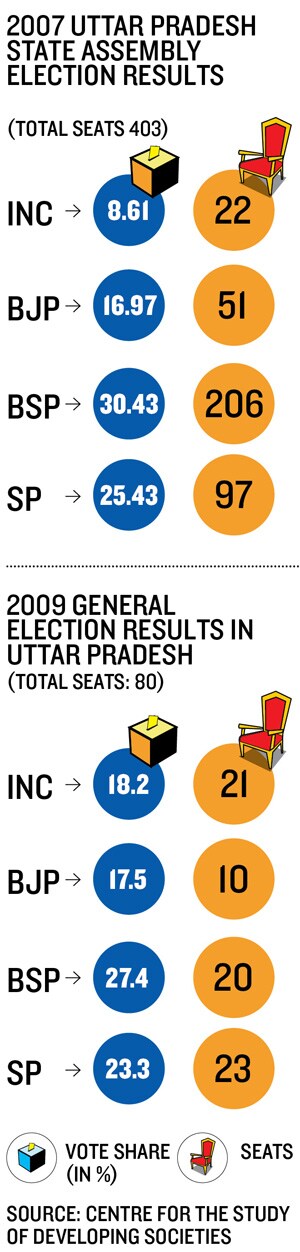

The elephant in the room, so to speak, is Uttar Pradesh. It is the biggest state that alone sends 80 representatives to the 544-strong Lok Sabha. UP has enough seats to give the ruling UPA a majority in the Rajya Sabha. Moreover, Congress’s future leader and possibly Manmohan Singh’s heir, Rahul Gandhi has put his full political weight behind winning the state, which was until two decades ago, Congress’s stronghold.

A good showing in UP would also have a salutary effect on the credibility of Singh’s government which has been on the brink of being ousted ever since the 2G spectrum scam broke in 2010. For a while now, Singh has been fighting fire on all fronts—erring ministers, opportunistic allies, stubborn Opposition, questioning civil society and a bloodthirsty media. Almost as a result of the stalled decision making, Singh’s grip on the economy has weakened and economic variables like inflation, growth and currency are running amuck. He hopes state election victories would indicate his government enjoys the people’s confidence. That is why UP is so crucial to the Indian economy in general and investors in particular. The elections provide Singh with that critical ‘knife’s edge’ path which he and his party must tread to avoid a political collapse.

Ajay Rai wraps his shawl tight around his shoulders as if to restrain the power that exudes from him within its woollen folds. He listens intently as a man tells him how the body of his son who had died earlier had not been released from the hospital for several hours. He shakes his bald head, then picks up one of the two mobile phones lying on the table in front of him and talks briefly. Done, he tells the man. He can go to the hospital and take the body. The man touches Rai’s feet gratefully and shuffles away.

Ajay Rai is the Congress Party’s candidate from Pindara constituency abutting Varanasi, the oldest continuously lived human settlement in the world and one of the holiest for Hindus. This is the Bharatiya Janata Party’s stronghold, but Congress is sure to win Pindara in the upcoming elections, many people there say. Rai has won Kolasla, as his constituency was known before delimitation, three times for the BJP. In 2009, he quit the party over differences with Murli Manohar Joshi and contested the elections against him on a Samajwadi Party ticket, giving the top BJP leader some nervous moments until the last votes were counted. He has now joined the Congress on an invitation from Rahul Gandhi. Many, including his rivals, say that he wins on his own steam because of his excellent rapport with the public. It also helps that he is what people here call a bahubali—strongman.

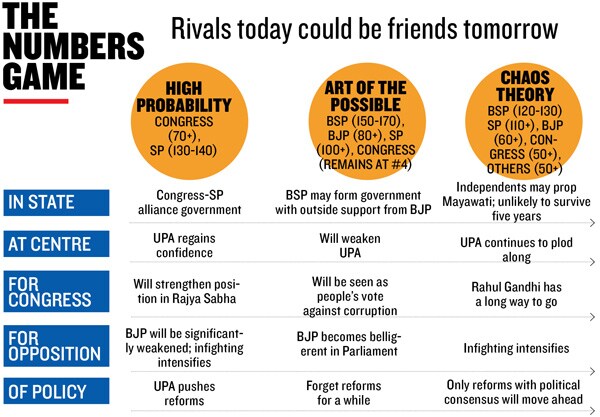

The UP election will test the mettle of many leaders but none more than Congress general secretary Rahul Gandhi’s. Many see UP as the rite of passage for the Gandhi scion before staking his claim to run the country. After remaining out of power in the state for 22 long years, the party hopes to make a comeback. A good show would breathe fresh life into the government at the Centre which has been half paralysed by Anna Hazare’s onslaught and brittle confidence in Parliament. It may not win a majority by itself, but hopes to get at least 100 seats, five times its current strength. A 70-100 seats tally would be seen as a victory for Gandhi who has relentlessly focussed for more than two years on a state where party organisation is virtually non-existent. Gandhi has travelled wide and deep into remote hamlets and visited Dalit households on people contact programmes, trying to drum up support for his party.

Having taken the reins of the UP campaign, Gandhi has hitched the fortunes of the Congress Party and the government led by it at the Centre to his own political future. A loss of face in UP would nail the party to the ground nationally, perhaps even forcing a general election much before 2014. A good performance would cement Gandhi’s position in the party and Parliament, giving his voice more weight. It would also embolden the Congress to swat down its cavilling allies and the obstructive Opposition. Gandhi and the Congress are leaving no pebble unturned. He has pitched himself as the agent of change while party strategists like Digvijay Singh continue to play the old game of community and caste-stacking.

“Highest on RG’s priority list is the implementation of National Food Security Act as well as the UID [Unique Identification Number] since they are two sides of the same coin: One will provide the subsidised food and the other will plug leakages from the system of delivery,” says a close Rahul Gandhi aide about the policies most likely to be executed post election. Gandhi is unhappy that UID implementation ran into rough weather after a confrontation between the Home Ministry and Planning Commission and is eager to put his weight behind the Nandan Nilekani-led effort to provide a unique identity number to the citizens, he said.

Gandhi upped the ante against the incumbent Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) government in June last year when he jumped into a farmers’ agitation against land acquisition in Bhatta Parsaul. Since then, he has raised his pitch against Chief Minister Mayawati, calling hers a hopelessly corrupt government that was skimming away money the Centre was providing for UP’s welfare. But corruption is rarely a big issue among a large number of UP’s inhabitants for whom social justice is paramount. Religion and caste are the most decisive factors in UP.

There is an apocryphal story about Chaudhary Charan Singh, former prime minister and father of Congress’s latest ally Ajit Singh. In 1967, Singh, himself a Congressman from UP, drew up a list of 40-odd castes which were hitherto ignored by the political class. He promptly launched the Bharatiya Kranti Dal and declared himself the leader of these ‘backward’ castes. Almost overnight people belonging to such castes like the Yadavs and Kurmis pledged their allegiance to Singh, making him a heavyweight in UP’s politics.

Whether the story is true or not, caste has played a prime role in the state’s electoral politics since the mid-70s. In 2007, Mayawati came to power, backed by an unlikely mélange of voters comprising Dalits and Brahmins, who had not voted with each other for many years. Both these communities, along with the Muslims, had formed the Congress Party’s vote bank in the post-Independence years. Later, the backward castes rallied behind the Samajwadi Party led by Mulayam Singh Yadav. When the BJP created a Hindu nationalist wave in the late ’80s and early ’90s with leader L.K. Advani’s rath yatra demanding a temple at Ayodhya at the very site that a mosque, believed to have been built by Turko-Mongol conqueror Babur, stood, it took away the Brahmin votes. In 1992, when Hindu nationalist volunteers clambered on top of the mosque and demolished it on the watch of a BJP government in the state and a Congress government at the Centre, Muslims en masse moved to Mulayam Singh Yadav.By the late 1980s, the Kanshi Ram-led BSP had started weaning away the Dalits too and by the mid-90s, Mayawati had risen as a symbol of Dalit assertion.

Within the span of a few years, the Congress Party’s vote bank had been divided up by the BJP and the two regional parties. It has since not recovered.

Now Rahul Gandhi is trying to rebuild the base with a promise of good governance and clean politics. “In the last 22 years you have given BSP, BJP and SP three chances each. Now give us just one chance,” he pleaded with predominantly rural voters at a rally in Bhathat, on the outskirts of Gorakhpur. It is a tough task to make people believe when his party leads a government at the Centre besieged with allegations of corruption, non-performance and indecision. But then other leaders in the state have also failed to keep their promises.

The BSP government came to power offering clean government and sarvajan hitay or welfare for all. While it did work to uplift its core constituency of Dalits, BSP mostly ignored the rest, say political analysts.

Mayawati’s schemes like Ambedkar Gram, which involved rapid provisioning of essential services like water, electricity and roads in a Dalit-dominated village, have worked like a charm in most cases.

“However, in the name of Brahmins, she has just showered benefits to the family members of S.C. Mishra, her close confidant. Brahmins feel cheated and will not vote for her again,” says a Brahmin retired bureaucrat in Lucknow. Muslims also resent most schemes meant for their development being named after Dalit leaders instead of Muslim icons like Sir Syed Ahmed.

However, within the first couple of years in office, the Mayawati government had earned a reputation for corruption. A BSP insider says that corruption has now become institutionalised in the party. Even those close to the party are not spared. He talks about an encounter with a government official who asked him for money to get his work done. “He was a good friend of mine. But he was helpless. He said he would have to pay the party out of his pocket if he did not take it from me,’’ he said on condition of anonymity.

Om Prakash Singh, professor Madan Mohan Malaviya Institute of Hindi journalism at Kashi Vidyapith, says BSP officials controlled the entire allotments in the Kanshi Ram Housing Scheme. Singh believes it will be very difficult for Mayawati to retain power. That does not mean that BSP will be wiped out. Far from it. BSP has a core vote bank of Dalits that never deserts it and is enough to bring it at least 70-80 seats. But nobody is expecting BSP to repeat the feat of five years ago.

“With a division of the floating Muslim vote [between SP and Congress] and Brahmin vote [between BJP and Congress], BSP could retain 130 to 140-odd seats, yet it would have to depend on other parties if it wants to form the government,” says Badri Narayan, professor of political science at the Govind Ballabh Pant Social Science Institute in Allahabad.

Mayawati has tried to clean up the perception of being corrupt by throwing out of the party anyone who attracts charges. She purged 21 ministers from her cabinet within 15 days of the announcement of polls on December 24, 2011. The purge may not have had much effect in improving BSP’s image and would have even worked against the party as many of the expelled members would have left with blocks of votes that they commanded as community leaders. But it worked in a very perverse way—BSP’s dirt stuck to BJP.

BJP was quick to welcome the BSP discards into its fold with a party ticket. It created such a furore within the party and divided even the top leadership that for several days, the focus of the state was squarely on BJP rather than the incumbent. BJP workers and ticket hopefuls who had worked hard for relevance in their constituencies were angry. For a party with a strong cadre base and dedicated workers hoping to make a comeback, it was disaster. The party trying to appease backward communities may also drive away some of the upper caste voters.

“The Kushwaha factor has damaged the BJP’s chances by 50 percent,” says Ajay Singh of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and former president of Indo-global chamber of commerce. Singh was referring to BJP welcoming Babu Singh Kushwaha, the BSP discard with many allegations of corruption against him, into the party and offering him a ticket. After tremendous pressure from within the party and scathing criticism outside it, the top leadership postponed his induction till he was cleared of all charges, a proposal mooted by Kushwaha himself.

BJP also delayed announcing its candidates to many constituencies. “There is no time to campaign. Other candidates have already visited voters a couple of times. Why would any voter even look at us?’’ a ticket hopeful said on January 11. Its traditional voters are the Brahmins and Bhumihars, and Baniyas. This time, however, Brahmins and Bhumihars, together close to 15 percent of the population, are still undecided. Feeling let down by Mayawati, they are certain to drift away from the BSP. However, which camp they would end up in is an open question. If the Brahmins and Bhumihars desert the BJP, it would be relegated to the fourth position. The most likely beneficiary of such a move could be the Congress as that alternative is more palatable to the two communities than SP.

Mulayam Singh Yadav’s SP was considered to be doing well until recently as his Australia-educated son Akhilesh Yadav drew large crowds during his kranti rath yatra. Whether these crowds will vote for SP is anyone’s guess. But SP also has the advantage of having an unflinching vote bank of Yadavs and a strong party machinery spread across the state that can cajole voters to the polling booth on election day. The Congress’ announcement of carving out reservation for backward Muslims from the existing OBC quota has put SP in a quandary, which can neither oppose nor support the move as it is bound to annoy either Yadavs or Muslims.

“There is no doubt that Congress has set the agenda in this election and both BSP and SP have had to respond,” says Ajay Jakhar of Bharat Krishak Samaj, a non-political association of farmers.

The people of UP have also not forgotten Mulayam Singh’s previous term when armed thugs and henchmen roamed the streets. It goes to the credit of Mayawati that she made the streets of the state safe for the layman. “At least there is law and order on the streets. You can see a few policemen on each crossing,” says a man in his mid-20s while roaming inside Ambedkar park in Lucknow along with his girlfriend.

Another factor that is likely to queer the pitch for the established players is the relatively young Peace Party. Formed in Gorakhpur by liver surgeon Mohammad Ayub, the party contested just one-fourth of the 80 seats in the Lok Sabha elections of 2009. Though a rag-tag, opportunistic coalition of disgruntled independents, the Peace Party can still upset the calculations of the biggies in several constituencies in eastern UP, especially since this time it has tied up with another 12 similar parties like Apna Dal and Bundelkhand Congress, to form the Ittihad (unity) Front.

“Irrespective of the eventual result, I can guarantee that no one can form a government without our help this time,” says a confident Raja Bundela, leader of Bundelkhand Congress.

Gravity of the Centre

Elections to the five states of UP, Punjab, Uttarakhand, Manipur and Goa—almost one-fourth of India in electoral terms—have brought decision-making at the Centre virtually to a halt. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh indicated in a rare interview to Bloomberg News that things would start moving after the elections are over. For instance, Singh said in the December 14 interview that he will succeed in letting foreign companies buy majority stakes in Indian retailers after contesting regional elections and as slower inflation bolsters support for his administration.

The government would be prepared to take on its mercurial allies such as Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress and also withstand pressure from the Opposition in Parliament if it does well in the states, especially UP. Although, even close Rahul Gandhi aides understand that the lack of organised cadres and capable local leadership may result in Congress falling well short of the 100 mark.

However, in a scenario where Mulayam Singh Yadav’s SP is in a position to try and form a government with some support from others, if the Congress manages enough seats to give that support, it could change the coalition equations at the Centre. Mulayam Singh has already pledged his unconditional support to the UPA until 2014. That could be further cemented in the case of a state-level alliance. Gandhi too has already begun to make belligerent statements on policymaking. “We will bring a strong Lokpal bill in the next session of Parliament regardless of opposition,” he said while addressing the press in Ballia on January 10.

With economic conditions such as inflation beginning to ease up, an election boost could help the government get on to the fast track. At a closed-door interaction with industrialists, the Prime Minister is believed to have said that they need to be patient with him until the elections are over.

He also requested them to not go public with their complaints seeking understanding that he could not fight a battle on several fronts.

Businessmen have kept their investment plans on hold. Fears that Indian capital is taking flight also seem to be unfounded. Latest RBI data showed that Indian companies’ direct investments abroad in the first nine months of fiscal year 2012 fell 28 percent to $25 billion compared to the previous year, belying assertions by many corporate honchos, who were lamenting a capital flight because of a vitiated domestic environment. A Congress Party victory could be a big boost to the industrial sentiment.Yet, there are apprehensions about what could happen if Gandhi becomes more powerful in the party, considering that his stand on critical issues where votes meet reforms is demonstrably left of centre. His views on land acquisition for industry and mining are not exactly music to their ears.

Broking firm Edelweiss expressed apprehensions about what could happen if Gandhi’s stature as a leader of the UPA is fortified. “It will also give a message for the Congress leadership that the party’s social sector programmes are reaping rich political dividends, far outweighing the negative publicity received due to allegations of bad governance. This may hinder the fiscal consolidation process, hurting the economy’s medium-term growth prospects,” Edelweiss researchers said in a report dated January 12.

Rasheed Kidwai, associate editor of The Telegraph and a long-time observer of Congress politics, feels such fears are unwarranted.

“If you look closely, the central agenda of the Congress-led UPA has always been ‘social left’ and ‘economic right’,” says Kidwai. Essentially, it means that there will always be a pro-poor tilt to policies but as far as economic structure is concerned, it will follow right of the centre ideology.

Seen from this prism, one can expect not just speedy implementation of right to food and land acquisition but also clearing the decks for foreign direct investment in retail and other stuck legislation like pensions reform in 2012. Judging from the little that he has talked about it, Gandhi strongly favoured FDI in retail which was stalled by the Opposition and alliance partners.

Kidwai feels Congress would be able to step on the legislative agenda if it does well in these elections not just because of the added numbers but also because of the salutary effect a win would have on the Congress and UPA’s credibility.

While most analysts believe Gandhi would definitely play a greater role in national policy making—some say even after a poor result—few expect a change of leadership at the Centre.

“Congress has never changed a sitting PM. This is a party which respects its leaders,” says a senior political analyst in New Delhi who did not wish to be identified.

Yet the political equations in the upcoming state elections, especially UP, seem to change every day and to aptly describe it, one needs to borrow Bob Dylan’s immortal lyrics:

And don’t speak too soon

For the wheel’s still in spin

And there’s no tellin’ who

That it’s namin’

For the loser now

Will be later to win

For the times they are a-changin’

Among the two national parties that are fighting Uttar Pradesh assembly polls, Congress Party and its general secretary Rahul Gandhi have the most at stake. A loss of face in UP will affect Gandhi but not enough to make a serious dent in his standing in the party. But the principal national opposition BJP and its president Nitin Gadkari, will be teetering on the edge if the party does badly in the state.

While the BJP was not in a position to win the elections on its own, it was expected to do better than its previous showing in 2007. All that changed when it decided to roll out the red carpet to a few discards, particularly Babu Singh Kushwaha, from the BSP. The plan to induct Kushwaha, who has serious allegations of corruption levelled against him, blew up in the central leadership’s face. Party insiders say that the plan was the brainchild of Gadkari, Kalraj Mishra and Vinay Katiyar and the rest of the leadership, including veteran L.K. Advani, was kept in the dark.As soon as the decision was announced, all hell broke loose. Senior party leaders such as Uma Bharti, Maneka Gandhi and Yogi Adityanath expressed their displeasure publicly. Even Advani is said to have been distraught telling a friend privately, “How will I face the voters of UP now?”

Some quick damage control did help keep the flock together, but the episode has put president Gadkari on a politically risky wicket. A strong performance in UP will strengthen him, but if that does not happen, Gadkari’s head could be on the chopping block.

Apart from the Kushwaha factor, partymen in the state are also unhappy with the way tickets were distributed. BJP had conducted a secret survey to assess the chances of ticket-seekers. The survey was skewed and in many cases tickets were given to undeserving persons, according to a veteran BJP worker in UP.

Vishwa Hindu Parishad leader and former president of Indo-Global Chamber of Commerce, Ajay Singh says that BJP’s candidate selection has been poor. “The stalwarts want their disciples to fight elections,” Singh told Forbes India at his home in Varanasi. Some party leaders are believed to have already started plotting against Gadkari. The party president would be in for some rough weather post-elections.

First Published: Jan 30, 2012, 06:33

Subscribe Now