The Amul Girl: Why she's still standing

In a world of slick celebrity endorsements, she has survived on witty humour, timely punchlines and old-school charm

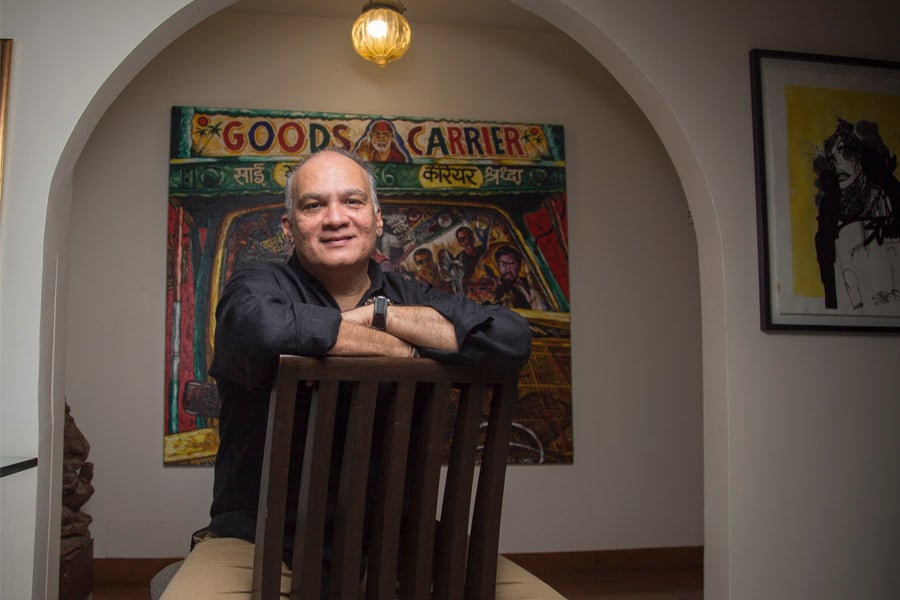

Rahul daCunha, owner and creative head of daCunha Communications, says the crucial thing about Amul ads is at what time of the curve they catch the issue

Rahul daCunha, owner and creative head of daCunha Communications, says the crucial thing about Amul ads is at what time of the curve they catch the issue

Image: Joshua NavalkarWhen four militants attacked an Indian Army brigade headquarter in Uri, near the Line of Control in Jammu & Kashmir, killing 17 army personnel on September 18 last year, it was called the deadliest attack on security forces in the state in the past two decades. Opinions and views filled the media space, but one commentator remained inexplicably silent.

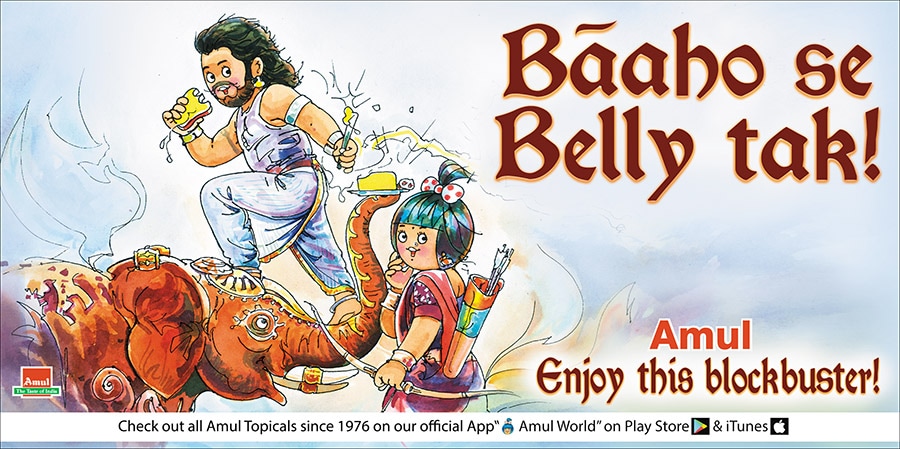

Ten days later, when India carried out surgical strikes in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, killing 35-40 terrorists and nine Pakistani soldiers, the commentator finally spoke up: ‘Surgical strikes. Amul: Paks a Punch’ said the little girl, usually seen donning a red polka-dotted dress, but now wearing army fatigue, rifle in hand, taking aim.

That the Amul Girl will have something to say on the most current issues and significant events is what people have come to expect. She’s been doing so for the last 50 years.

And this is what has kept her relevant and thriving in a world where advertising mascots have either long faded, been abandoned or replaced by celebrities. “She is not opinionated, but an opinion leader for sure,” says Harish Bijoor, brand expert and founder, Harish Bijoor Consults Inc. “Other brands that built endearing advertising woven around their brand icons are Air India (AI) with its Maharajah, Asian Paints with Gattu and Nerolac with Woody the Tiger. But Woody and Gattu are in the graveyard of icons and the Maharajah has undergone changes, including bariatric surgery. The Amul Girl is the only one standing short and cute.”Bijoor’s references hark back to a time when brands opted to create and build mascots to represent their brands. In India, one of the earliest examples was the portly Maharajah, created in 1946 by SK Kooka and Umesh Rao of advertising agency J Walter Thompson. “The Maharajah is around 71 years old,” says Dhananjay Kumar, spokesperson for the airline. “Earlier, aviation services were limited to a few rich people. That’s why we had chosen a maharajah. But after the merger of Indian Airlines and Air India in 2006, we changed him to slim from fat, and made him stand straight instead of bent forward.” But with the changing profile of the Indian flyer, and with the airline connecting smaller cities and not just metros, the Maharajah has donned new clothes.

“Mascots were necessary in the earlier days of brands because of lack of literacy,” says Piyush Pandey, co-executive chairman and national creative director of Ogilvy & Mather (O&M) India and vice chairman of O&M Asia-Pacific. “Symbols were remembered by people much better. Though this has changed, in today’s India, mascots still make a difference.” O&M is the advertising agency behind the highly successful mascots of Hutch-turned-Vodafone: The ever loyal, lovable pug that came with the tagline ‘Wherever you go, our network follows’, and the wildly popular, frenetic world of the Zoozoos, which debuted with the 2009 Indian Premier League (IPL), but remained an IPL-season phenomenon. (After a short run of four seasons, Vodafone sensed viewer fatigue and dropped the campaign from the 2012 IPL.)

The use of mascots was born as a form of trademarking at a time when people could not read and identification was done visually, says KV Sridhar, advertising veteran and founder and chief creative officer of Hyper Collective. “People would identify the company by looking at the mascot—the monkey brand tooth powder, or the Murphy baby. Identification was image-led and the brands would trademark that image.”

The mascot then gradually came to represent the quintessential characteristics of the brand. For instance, “The Maharajah was a stereotyping that helped identify AI as an Indian airline,” says Sridhar, adding that the mascot evolved to become an ambassador of the brand, and not just a trademark. “That is when the Amul Girl came in. She started talking to people like a living being, and went on to become more successful than Gattu. Gattu was just a trademark he never came to life. Woody the Tiger was also just a mascot. Tony the tiger of Kellogg’s, the Jolly Green Giant for B&G Foods, and Onida’s devil acted like spokespersons. But they could not sustain themselves,” says Sridhar.Over decades, as brands evolved to represent tangible value-additions and, even later, an emotional benefit, the mascot was no longer an essential element on the packaging, and began to make separate appearances. But apart from the evolution of brands, and the philosophy of branding, what also emerged were celebrities. “Celebrities are a shortcut to brand recognition. And we live in a world where everyone is looking for quick results,” says Tarun Rai, South Asia chief executive officer of J Walter Thompson. “Mascots require time and investment. So it is not surprising that we see more and more celebrities endorsing brands.” He adds that while celebrities give marketers flexibility, with a mascot there is the danger of becoming irrelevant.

Celebrities came into popularity as testimonials to the quality or class of a brand, says Amer Jaleel, chairman and chief creative officer, Mullen Lintas. “As differentiation between brands decreased and parity increased, I suppose celebrity endorsements gave a push to the validity of the claim by brands in that time,” he says.

But no matter what the change—and what the reasons behind it—may be, Amul’s wide-eyed moppet has seen, and survived, it all.

Nine years after the brand Amul was registered in 1957, Dr Verghese Kurien, its founder-chairman, decided to advertise the products and handed the account to an advertising agency called Advertising and Sales Promotion (ASP). Its team, headed by Sylvester daCunha and Eustace Fernandes, came up with the line ‘Utterly Butterly Delicious’ in 1966. Fernandes, who was the art director, was the one to design the little girl.

“At that time, advertising in press and on television wasn’t as simple. The agency, therefore, opted for outdoor hoardings,” recalls Rahul daCunha, 55, Sylvester’s son and owner and creative head of daCunha Communications.

‘Give us this day our daily bread and butter’ was among the first public appearances of the Amul Girl, where she is kneeling with her hands joined in prayer, and one eye mischievously peeking at the packet of butter. However, the team realised that if it was going to be a long-term campaign, they would have to look beyond an association with food. This led to the hoarding ‘Thoroughbread’ to herald the beginning of the horse racing season in Mumbai. Following that was an ad that played on the Calcutta [now Kolkata] labour strike slogan of the 1960s: ‘Bread without Amul—cholbe na, cholbe na [will not do]’.

The favourable feedback prompted Kurien to give complete independence to the agency. “This happened in 1966, when my father told Dr Kurien that you can’t put such a thing through a board meeting because it is not about the product. And the company agreed with just one caveat: ‘Don’t get us into trouble’,” says daCunha with a laugh.

By 1969, Fernandes moved on to form Raedeus Advertising while Sylvester founded daCunha Communications, which continued with the Amul campaign.

Besides Amul Butter, daCunha Communications handles 10 other Amul products, such as cheese and milk, and shares Amul’s account with FCB Ulka. It also handles digital advertising for Kokuyo Camlin and the Officer’s Choice brand of whiskey. “But Amul is a full-time job,” says daCunha. The agency has been growing its revenues by 25 percent year-on-year.

RS Sodhi, managing director, Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation, the holding company of Amul, says when he joined Amul 35 years ago as branch manager in Jaipur, one of his main tasks was to approve hoarding sites and ensure they were changed on time. “We had two hoardings in Jaipur and it took three to four days to change them. Every two years, the site’s price would increase because after putting Amul topicals, it would become an iconic site,” he says.From appearing on hoardings in Mumbai once or twice a month in the mid-1960s, today a ‘topical’ is churned out almost five days a week across multiple platforms—200 hoardings across the country, leading national and regional newspapers, as well as on social media platforms. The campaign also entered the Guinness Book of Records as the longest-running ad campaign in the world in the early 2000s, says daCunha. To celebrate 50 years of the Amul Girl, this February, the company released its third book, Amul India 3.0, a compilation of its best ads, with superstar Amitabh Bachchan and filmmaker Karan Johar as contributing writers.

The recipe for a good Amul topical is simple: Choose the right issue, represent it visually, and top it off with a witty remark. “Every Sunday, I talk to my writer Manish Jhaveri and we plan what we think are the seven or eight events for the week,” says daCunha. Jayant Rane completes the core team.

“Once we zero in on a topic, I give Rahul two or three options for the lines,” says Jhaveri, who has been writing the punchlines for Amul for the past 23 years. “He chooses one and gives it to Jayant. By then, we know approximately what the visual would be.” Jhaveri began working with the daCunhas as a full-timer in 1994 and continued to work as a freelancer on the Amul campaign from 1998 onwards.

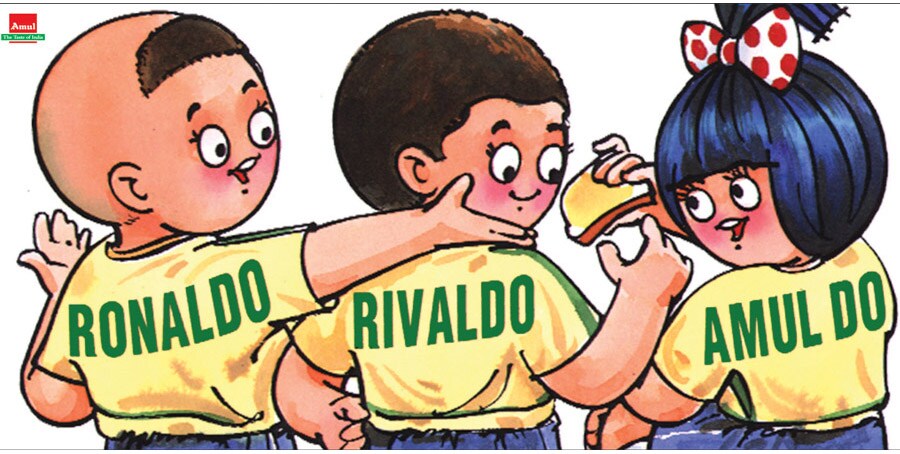

undefined Amul topicals are churned out almost five days a week and each one is still hand-painted [/bq] After the line is finalised, Rane begins making a rough sketch. “The unique part is that every topical is still hand-painted,” says Rane, who has also been a freelancer with the agency for the past 30 years. Jhaveri says the detailing makes Amul ads stand out. “Otherwise you have so many line drawings that are used. But none has the fineness of the lines that Jayant adds to the pictures. To make any face look Amul-ish is quite a talent!”

The sketch, after being approved by daCunha, is posted on Amul’s social media handles some make their way into newspapers and on hoardings.

“The most important thing is at what time of the curve we catch the issue,” explains daCunha. “We have a quick turnaround for most issues, but sometimes we wait and watch to see if it takes on a new meaning.” For instance, even before the Olympic final of PV Sindhu had begun, their drawing had started. “Because whether she won or not, she had made history,” he says. “We were just waiting to colour the medal gold or silver.” But they also need to be prepared for the unexpected. Like the Oscar gaffe, when the wrong movie was named winner in the Best Film category.

There have also been a few run-ins. For instance, when they created a topical on Tarun Tejpal, who was accused of sexual assault, the ad showed crows pecking a Tejpal-like figure seated in an elevator, and the Amul Girl standing outside. The tagline read, ‘Kya se kya kho gaya Amul—Tehelka macha de’. “We faced a huge backlash and were accused of belittling rape, which was never the intention. That is when I learnt that Amul is seen as a vehicle of humour. Even if you take a serious side, you are making fun of it. The nature of the campaign doesn’t let you venture into grey areas,” says daCunha.

Jhaveri believes that the ads should be funny, witty and sarcastic, but never hit below the belt: “It is easy to laugh by hurting people. That is the easiest kind of humour. What Amul has managed to do well for so many years is that if someone is at fault, he will know that we are taking potshots at him. But we aren’t throwing a stone we are throwing a pebble. That gentle sense of humour has resonated really well with the country.”

Jaleel says the Amul Girl has managed to be a standout act through sheer doggedness and persistence. Air India’s Maharajah, for instance, suddenly found itself in a new environment. “To modernise the brand imagery, the Maharajah had to be redesigned in order to connect to the middle class,” says Sridhar.

But that was not the case with the Amul Girl. “Amul has kept its values intact,” says Sridhar. “It provides a point of view, which is very light-hearted and charming. It is a much-loved brand. Rasna failed to do that. Liril failed to do that. But Amul could.”

No wonder the picture of the Amul Girl making a pertinent point is a sight hard to miss.

First Published: May 19, 2017, 08:08

Subscribe Now