Telecom Needs Variety Not Quantity

Focus needs to shift from infrastructure creation to reuse of resources and innovation

Bad regulation in India is an equal opportunity offender.

While those like MTS struggle for their very right to exist in India, older incumbents like Bharti Airtel, Vodafone and Idea are currently staring at the prospect of being “retroactively” charged an estimated Rs. 37,000 crore each for 10 years-worth of “excess spectrum” held by them. As state-owned BSNL is being progressively run to the ground, earnest private operators like Tata Teleservices have been waiting for start-up spectrum in a key market like Delhi for over four years. When a foolhardy new entrant pops up, like US-headquartered Qualcomm did last year and when it bid $1 billion for 4G licenses in four lucrative markets, its application was rejected for thoroughly frivolous reasons.

A mish-mash of secretive and uninformed regulators—the ministry of Telecom, TRAI, Department of Telecom, TDSAT—work at cross-purposes with each other. Operators and other stakeholders come to know of regulations via frequent “leaks” to the media, in most cases traced back to unauthorised photocopies of official documents that are palmed off and sold by junior staffers. The phrase “regulation through photocopy” would not be out of place, most stakeholders agree in private.

With nearly 900 million subscribers across seven to 15 operators (depending on whether you include the ones whose licenses were cancelled), regulators ought to understand Indian Telecom is no longer in its infancy.

“The whole idea of prescribing how an eighth, ninth or tenth operator should roll out their networks doesn’t make sense today. Consumers need service competition, not multiplicity of infrastructure,” says Mahesh Uppal, a telecom policy expert and Director of consulting firm, Com First.

There is a strong belief that this logic of introducing many more operators in each regional market may not be consistent with how wireless telecom has evolved across the world. According to the credit rating agency CARE’s research, on an average there were 15 players (both GSM and CDMA) in a telecom circle in India as compared to three in Singapore, three in China, four in Mexico and five in the US. There are at least five operators, namely Uninor, S. Tel, Videocon Telecommunications, Loop and Sistema Shyam, who had less than 1,000 subscribers in various licenced areas. Out of the total 122 cancelled licences, 39 licence areas (about 32 percent) were highly under-utilised as these five operators did not even have 1,000 subscribers in those circles as of December 2011, implying the services were not fully rolled out. And here’s a telling comment on the state of the industry: After the cancellation of licences, average number of operators will come down to around nine to 10. A 2009 Government of India Report on Spectrum allocation on page 12 says: “This indicates that further entry of operators beyond four or five does not significantly increase the competitiveness of the market.” And what do the fringe guys have to show for their efforts? A $2 billion pan India network without any subscribers!

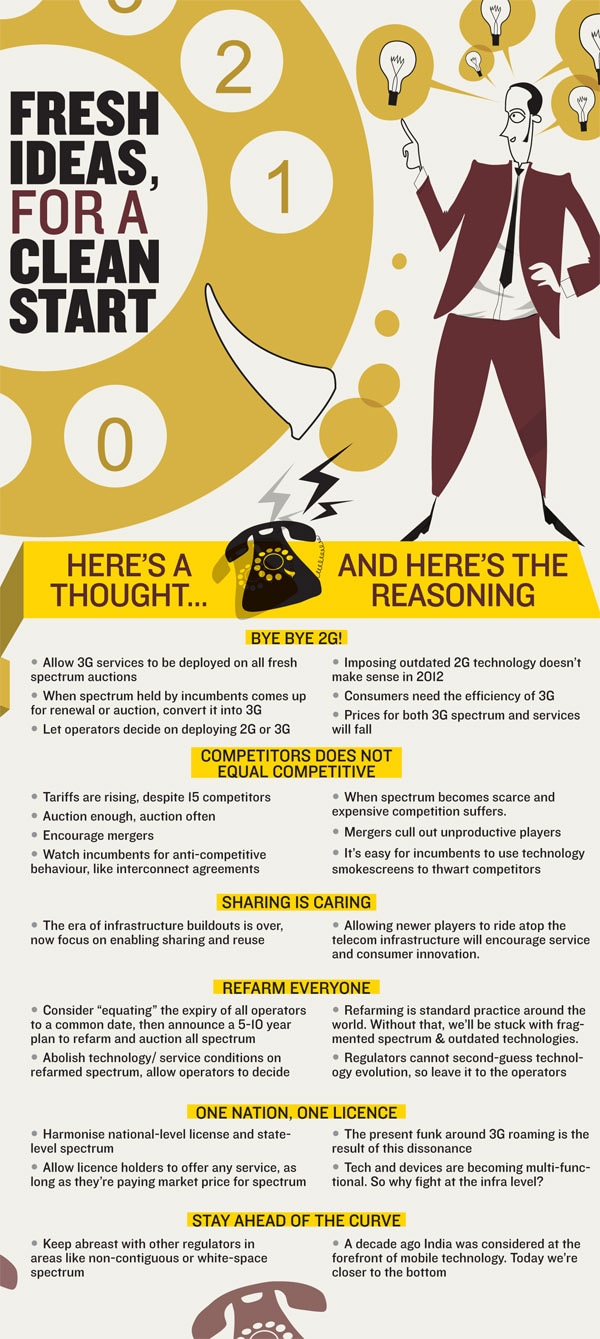

Hence, focus needs to shift from infrastructure creation and network rollout towards reuse of resources and innovation.

“The concept of tower sharing that began four to five years ago was a great milestone. It showed operators realising there is more value in sharing assets than in keeping them to one’s self,” says Srinivas Addepalli, senior vice president, Corporate Strategy at Tata Communications.

Instead of penalising operators for sharing scarce resources, as the drive against “illegal 3G roaming” indicates, the regulator should encourage all forms of asset sharing, including spectrum, provided consumers aren’t being short-changed.

Then allow MVNOs (virtual operators who lease the infrastructure from other operators) so idle assets can become economically productive platforms for consumer innovation.

Once this freedom is established, the wholesale market will naturally begin to evolve. Players like Lightsquared, a company that is building a $7 billion wholesale-only 4G network across the USA, could make eminent sense in broadband-hungry India.

“Wholesale should be very seriously encouraged. In fact, for BSNL it could be a brilliant option, given its huge strength in infrastructure but almost nothing on the retail side,” says Uppal.

Encourage mergers, by doing away with all restrictions on spectrum held and increasing the combined market share level in consultation with the Competition Commission of India (CCI).

“The reason why most telcos merge is spectrum. Of what use are customers or cell sites without the spectrum to service them with? By imposing artificial constraints on mergers, you prevent market forces,” says Addepalli.

Instead of worrying about how many operators can exist, determine how many should.

“While the minimum number could be as low as four, the regulator’s own analysis has shown there is no significant consumer benefit beyond six operators. So maybe they can fix six as the minimum,” says Uppal.

When it comes to mergers, fears of cartelisation or monopolisation are almost always overblown.

In India cartelisation should have been done by the incumbents—Airtel, Vodafone and Idea. But most of the tariff innovation has come from Tata Teleservices or Reliance Infocomm while the data innovation has been done by Aircel. So where is the cartelisation, asks Kunal Bajaj, director at Analysys Mason, a telecoms consulting firm.

He goes on to suggest that the concept of regulators determining the number of operators is itself outdated. “Today we have technological and economic solutions like spectrum and network sharing, so you can even have 20 operators. In fact, the concept of an operator being an end-to-end entity needs to be rethought. They can be just a customer facing entity,” he says.

“Regulators should become innovative and forward looking, and behave like economists. Unfortunately, I don’t think they understand even basic EMI calculations,” says Syngal.

Operators and other stakeholders come to know of regulations via frequent “leaks” to the media

First Published: Feb 20, 2012, 06:16

Subscribe Now