Is Google Gobbling Up the Indian Internet Space?

Google has a staggering amount of control over the Indian internet space. That can't always be good

To the average indian internet user, Google is oxygen—omnipresent, free and essential to her existence. Whether it’s a web search, watching a video, using a browser, the operating system for smartphones or plain and simple email, Google is everywhere—and free.

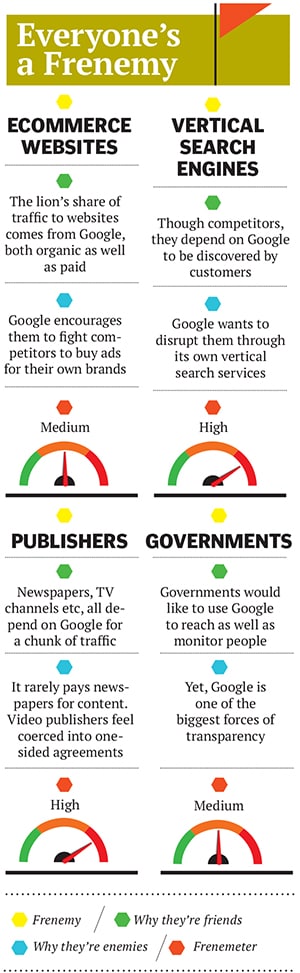

But someone is obviously paying for it all. And among them, an increasing number think of Google as an adversary in the garb of a friend, someone who inserts himself between their customers and themselves, and charges what they see as an unreasonable tax on the oxygen essential to ecommerce.

Take apparel ecommerce, for starters.

Sometime early this year, three of India’s biggest players in the space—Jabong, Myntra and Yebhi—came to a stark realisation. Nearly one-third of the Rs 1.5-2 crore each of them was spending every month on Google search ads was spent on ambushing each other’s potential customers, often with little bang for the buck.

The three had been engaged in a bruising bidding war for ads related to their own “brand searches”

—ads shown to users who searched Google for, say, “Jabong.com ” or “Jabong”. But in their zeal to snatch potential customers a second or two away from clicking through to a rival’s website, and conversely to defend their own brand searches from rivals, they had all bid up the cost-per-click (CPC) rates for such ads through the roof (CPC is the money paid by an advertiser for every customer that clicks on its ad).

As they saw it, Google was the proverbial monkey pretending to settle a dispute over a cake between two cats, while ending up eating the cake.

“Google is sucking all the air from the ecosystem. No matter how good your business is at a gross margin, they just skim the cream off everyone,” says the co-founder of one of India’s leading travel portals.

With profits still a mirage and venture capital money fast running out, the companies put aside their fierce rivalry and reached out to each other informally. A decision was taken to stop bidding on each other’s brand searches. Naturally, CPC rates for brand search ads plummeted drastically, as companies were often the sole bidders for their own brand searches.

But this is where the story takes an interesting turn. According to insiders with access to what went on after this informal deal, some of the three apparel companies received calls from their sales contacts in Google.

“Why have you stopped bidding on competitive brand searches? This is very risky. The Indian ecommerce sector is still nascent, which means that even when a customer is searching for Myntra, she might be open to switching to Yebhi,” they were told.

But the companies decided they couldn’t bleed any more. Today, one of them says, it spends just about 10 percent of what it once did on brand searches.

A similar truce also exists in the travel space, where three of the biggest players, Makemytrip, Cleartrip and Yatra, are learnt to have informally agreed to not target each other’s potential customers.

But no such luck was forthcoming to Matrimony.com, the largest online matrimonial service in India. After tasting success with their Bharatmatrimony.com service, the company had rapidly created numerous offshoot websites like Tamilmatrimony.com and Bengalimatrimony.com, each of which was duly trademarked as well. In 2008, it drew $11.75 million in venture funding from Yahoo! and Canaan Partners.

Since 2009 it has been waging a dual legal battle against Google alleging the search giant willfully allows its competitors like Shaadi.com to advertise themselves to users searching for ‘Bharat Matrimony’ or many of its other trademarks. (One may ask: Why would users type Bharat Matrimony if they already know the site they want? They can go directly there. But this practice is common among lay users, who happily let Google auto-complete the URL.)

In the courts (first the Madras High Court, where it lost, and now the Supreme Court) Bharatmatrimony.com is arguing that Google adopts “double-standards” towards brand searches, disallowing ads for its own or large global brands like Citibank, Facebook or ICICI Bank, even while encouraging the same for smaller Indian brands. It has also filed a case with the Competition Commission of India (CCI) alleging discriminatory trade practices.

During the past few years, Google has firmly cemented itself into the daily lives of India’s internet users, reaching them across economic and geographic barriers. According to Comscore, its services reach over 95 percent of India’s 137 million internet users.

Having been shut out of the world’s largest internet market, China, due to political reasons, India is Google’s biggest bet for the future after the US.

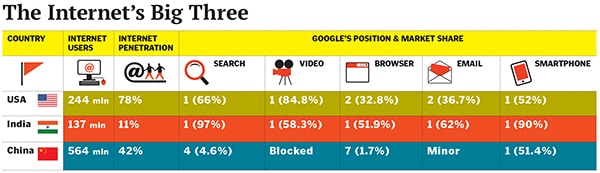

Why? India has the third largest internet user population in the world after China and the US. More importantly, only 11 percent of its population is online yet, compared to 42 percent and 78 percent for China and the US, respectively. In no other large country in the world does Google enjoy such overwhelming market shares across all its major products as it does in India (see table below).

Though Google India’s 2011-12 revenues of Rs 1,162 crore may not immediately reflect the strategic importance of the Indian market (its annual global revenues in 2012 were over $50 billion, or Rs 300,000 crore at Rs 60 to the dollar), India is reportedly its fastest growing major market globally.

“While companies like Microsoft, IBM and Oracle were treating India like a back office all these years, Google was the only company that realised its potential as a market,” says Mahesh Murthy, a partner with venture capital fund Seedfund and the founder of digital marketing agency Pinstorm.

Google’s success in India, and around the world, is testament to its meticulously-designed, fast and no-nonsense products, of course. From search to email to video to smartphones, Google came in as a laggard but ended up as the undisputed leader based solely on the appeal of its products.But each win has emboldened and equipped Google with insights on new markets to disrupt, products to build and intermediaries to sideline.

Under Larry Page, its co-founder and returning CEO, the company is moving away from its traditional role of being a horizontal search engine delivering information, to being a “specialised” one enabling transactions.

“Users are looking to get closer and closer to answers. That is the evolution of our product,” says Rajan Anandan, managing director of Google India.

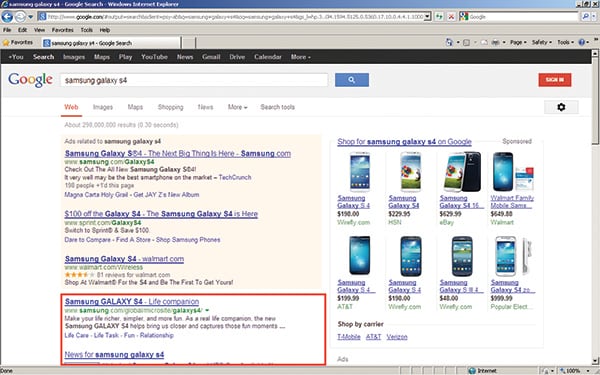

Search for a flight number or travel route and Google will offer you results from its own ‘Flight Search’ service first, instead of merely pointing you to a Cleartrip.com or Makemytrip.com. Search for a Samsung Galaxy S4 smartphone and Google will show you multiple sellers listing the same in its ‘Product Search’ service instead of a price comparison site. Search for a local business or restaurant and you are likely to get a Google+ page displayed most prominently, instead of a Justdial.com or a Zomato.com.

Websites that were once close partners with Google may wake up one fine day to realise they’ve been “disrupted”, as their search traffic is diverted to one of Google’s own services. In short, Google is now often competing with its former customers.

Among publishers too, Google is treated warily. “For 90 percent of publishers, Google will be their biggest advertising provider. Other than advertising, Google contributes a minimum of 30 percent of any publisher’s website traffic,” says the head of one of India’s largest media and publishing companies.

Thus, partners and customers warily treat it as both a threat and an opportunity. A friend and a sort-of enemy—a ‘frenemy’.

Of the nearly two dozen people Forbes India spoke to for this story, none were comfortable saying anything even remotely critical of their frenemy, Google, on record. Many refused to be quoted at all. Reason: When the bulk of online sales depends on one company, you can’t afford to antagonise it.

A BENEVOLENT MONOPOLY?

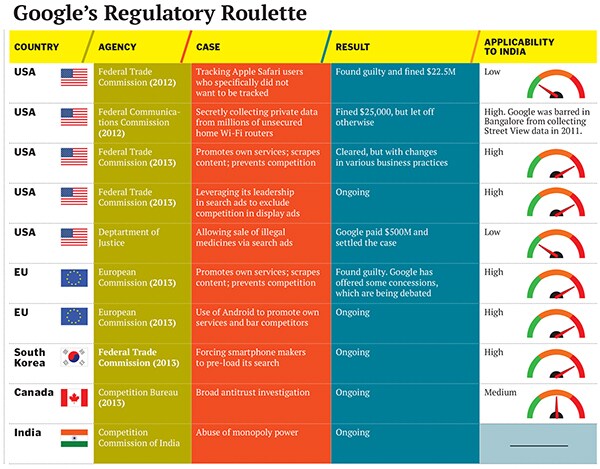

“Is Google a monopoly?” is a question that is being asked, debated and answered more and more frequently by regulators around the world. In India, the nodal Competition Commission of India (CCI) is evaluating its own answer to that question in response to two complaints against Google, one from Matrimony.com and the other from CUTS, a consumer rights organisation based in Jaipur.

With a 97.5 percent market share in India (source: StatCounter) and between 70-90 percent in most big countries, Google sits on a veritable cash machine. It is estimated to generate over $100 million (Rs 600 crore) every day globally from search ads, according to search marketing provider WordStream.

But Anandan strongly refutes the suggestion that Google is a monopoly. “Absolutely not,” he says. “On the internet, it is very tough to lock users in to any service because they can decide with just a click which service to use. Also, the cost of switching from one service to another is zero.”

That’s true at least in part, and modern competition law has evolved to accept the presence of monopolies, especially on the internet.

“There is a certain winner-takes-all effect in the online world, which often takes companies from around 20-25 percent of the market to 75-80 percent very rapidly. How many people know who is the number two player after Google in search, or after Facebook in social networking, or after Twitter in microblogging, or eBay in auctions?” asks Murthy.

Anandan also finds it “curious” how Google could be called dominant when its popularity is based on just 12 percent of India’s population currently being online. “As the market expands, newer segments will evolve. And the great thing about the internet is that past success is no guarantee of future success.”

However, the internet has seen many examples of past success transforming into future ones through the “network effect”, an inversion of traditional notions of customer value.

“On the internet, the utility value of a product or service to each user increases, often exponentially, as the number of other users increases. In the real world, it is often quite the reverse, like how the experience of owning and driving a car decreases as more people drive cars on the roads,” says Ajit Balakrishnan, the founder and CEO of Rediff, an Indian news, entertainment and shopping portal.

Over 95 percent of Google’s revenue comes from advertising, of which search ads account for the lion’s share. And search engines are what economists call “two-sided markets”, bringing together paying advertisers who subsidise free customers. The more the users, the more attractive a search engine is to advertisers. Conversely, the more advertisers a search engine has, the better it can invest in newer features or products.

Meaning, as the next segment of Indian consumers or businesses gets online for the first time, they will derive tremendously more value from Google’s products than its competitors.

“Sure I would have loved to have an alternate player with better features and pricing. But as it stands today, it’s far better to have Google provide a web infrastructure and charge a ‘tax’ for using it than to not have it,” says Alok Mittal, the managing director of venture fund Canaan Partners.

This is where regulators often try to answer a follow-up question, “Does a company behave like a monopoly?”

This, in turn, means seeking answers to several questions that follow—“Does Google take undue advantage of its market share?”, “Does it create insurmountable barriers for new competitors?”, “Does it charge extortionate prices to its customers?” and perhaps most importantly, “Does Google harm customers?”

In the Indian context, the answers are unclear.

CLICK THIS, NOT THAT

Over the years, as Google’s reach and power have grown, so have its motivations to put its financial interests over that of its search users or advertising customers. The amount of space it devotes to ad results has progressively gone up, with ads now appearing even before the actual results (earlier they only appeared on the right).

Google’s product and sales strategies are also dovetailing to ensure that no business can afford to ignore ads. Search for “Jabong.com” and the first result that appears is an ad by Jabong, followed by its number one place in Google’s organic search results. Clicking on either link will take you to Jabong’s website, though Google would very much prefer you to click the ad so it can make some money in the process.

This is like a company paying for its own customers. In a normal world, no company would buy ads to reach customers who are already searching for its website and are only a second or two away from landing up there. The only reason they would is if there is a risk of a competitor diverting those customers away with its own ads.

Many large advertisers told Forbes India how Google’s sales team fans advertiser insecurities by offering off-the-record “tips” about how their rivals run ad campaigns or plan to ambush their brand searches. But then, inducing customers to take a decision one way or the other could be something that all salespeople do.

Anandan says he is surprised to hear such allegations about his sales staff.

“If we hadn’t spent millions of dollars building our brand, no one would be searching for it specifically. I’m not sure what gives Google the right to sell ads on those searches,” says the travel portal executive quoted earlier on, adding that at one point his business was spending 15 percent of its overall online advertising budget targeting users already searching for it.

ANANDAN’S STRATEGY

Though India and Indians have always had a soft spot in the Google universe (four out of the 13 executives on its management team are of Indian origin), it was only with the arrival of Anandan as its India head in January 2011 that its local strategy really took off.

Anandan, a Sri Lankan by birth, came to Google after stints with McKinsey, Dell and Microsoft India (where he was managing director). Compared to his predecessor Shailesh Rao, whose focus was largely on product development or influencing policy, Anandan was much more ambitious and hard-charging about driving revenue growth from India.

Anandan is an out-and-out salesman with scant regard for the techno-geek culture that is thought to embody Google’s founding values. “Rajan knows how to convince CEOs on the potential of the digital business and what they’re missing out on. He’s a rocket,” says Rahul Kulkarni, who worked with Google India as a product manager between 2006 and 2012.

Buoyed by the rapidly increasing India revenues, Anandan has been able to convince Google to increase its investments in content licensing for YouTube, marketing and other long-term initiatives like ‘India Get Online’, a project to get small and medium businesses to start their own websites.

On a personal level too, Anandan, an angel investor in technology startups, never misses an opportunity to evangelise the power of internet commerce at most public fora. In April 2011, he was the first to publicise India’s 100 million internet users, while adding that the number would touch 300 million by 2014. HOW SUCCESS BEGETS SUCCESS

HOW SUCCESS BEGETS SUCCESS

“By the end of this year we expect there will be 70 million smartphones in India, and we are working hard with OEM partners to bring more affordable Android-based smartphones into the market,” says Anandan.

Android is a free operating system, so phone makers love it, which is why it has a 90 percent market share in India. But there are “hidden costs”. A leading phone maker alleges, again on condition of anonymity, that Google insists on making its own applications the ‘default’ option as part of the drill for passing its certification programme.

The default option is coveted by all internet companies because very few users bother to change those. Very few will be able to afford it though. As a benchmark, Google pays a reported $300 million a year to the Mozilla Foundation for being the default search provider on its Firefox browser. The market share Google gains through such deals is then funnelled back into newer services it spins out, called “specialised” or “vertical” searches.

To see this in action, search Google for the name of your favourite restaurant, gadget or a flight route, and you will often be presented with ‘boxed’ information directly from Google. The information often comes from products like Google+, its social network, or Google Places, its local listings services (and at times, Wikipedia). Google may thus be leveraging search to grow another business.

In the video space, where YouTube is the number one player, one publisher alleges that Google sometimes turns a blind eye to unauthorised clips uploaded by users in case the complainant isn’t a partner. Though Google does take down clips that infringe copyrights, it is apparently more diligent about doing so when the complainant is a business partner. “Between the impossibly onerous task of monitoring YouTube for illegal uploads all the time, versus handing over all your content to Google for publishing, most publishers resign themselves to signing up and taking their share of ad revenues,” says the head of the online media firm quoted earlier.

TOO BIG TO REGULATE

Google’s traditional response had been that all of its services were core to search, and thus there was no question of it favouring them. “The question of whether we ‘favour’ our ‘products and services’ is based on an inaccurate premise. These universal search results are our search service—they are not some separate ‘Google content’ that can be ‘favoured’,” said Google’s executive chairman Eric Schmidt in September 2011 in response to a US Senate Committee hearing.

But on April 23, the European Commission announced after an extensive investigation that it had, on a preliminary basis, found Google dominant in web search and search advertising by virtue of its market share which exceeds 90 percent in most European countries. It also said that in four areas Google may be abusing its dominant position, the first of which was “specialised search”.

Faced with the prospect of massive fines or being banned in the EU, Google offered multiple concessions, including a voluntary labelling of its specialised search services to distinguish them from natural results.

A key distinction between the European Commission’s treatment of Google versus the EC’s American counterparts like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) or the Department of Justice has been the focus on “consumer harm”.

Google’s position has almost always been that its (mostly) free products serve customers who are just “one click away” from choosing a competitor. And it can be very hard to really prove “harm” to consumers who use a free product. By and large, American regulators have followed the same principle. In January this year, a five-member FTC bench unanimously cleared Google of monopoly abuse after a two-year investigation.“The law exists for the benefit of consumers, not competitors,” says Anuj Puri, an independent lawyer specialising in competition law.

But the European Commission took a different view and said it “does not act to protect competitors as such, but to preserve the competitive process for the benefit of consumers,” and that “it is important for it to intervene in order to ensure that Google’s prominent market position in web search does not affect the possibility for other competitors to innovate in neighbouring markets, including in the long-term.”

“It’s hard to compete with Google’s ‘free’ products, so we try to avoid going head-to-head against them,” says the CEO of probably India’s only rival to Google Maps. To survive, he’s had to “keep on iterating and diversifying for the last six years”, retreating almost completely from the online maps space and opting for offline deals and OEM partnerships with car makers.

When Forbes India asked Ashok Chawla, CCI chairman, about the status of the two cases pending against Google, he replied via SMS, “The Google matter is under investigation. Thereafter the matter will come before the Commission for a decision.”

“In India, though the CCI is the successor to the older MRTPC, it is still what I would call a first-generation regulator. It is a ‘super regulator’, therefore does not understand issues around online competition in depth. To be fair though, I was amongst the most vocal critics of CCI, but have changed my mind after going through some of their decisions around stock exchanges and banking in which they have displayed great skill in analysing complex issues,” says Puri.

According to a confidential source, the two cases have apparently been clubbed together under the charge of Jyoti Jindgar, an additional director general. Jindgar is a Sebi official and has been on deputation from the nodal securities regulatory body since late 2010. To build its knowledge of the space, the CCI is also learnt to be collating inputs from its peers in the US, EU and Australia.

In India, where Google has a 97 percent search market share (see table on page 44) and where internet ecommerce is seen as the next evolutionary rung after IT service outsourcing, Jindgar will need to answer the question—can vibrant markets exist in the absence of vibrant competition?

THE GOOGLE PLATFORM

In December 2011 things appeared pretty bleak for Google after the union telecom and IT minister, Kapil Sibal, berated it (along with peers Facebook and Yahoo!) for not “pre-screening” user content for defamatory comments before it was uploaded.

Having been ejected from China for its failure to kowtow to the government, Google was, of course, extremely wary of losing its next biggest market the same way. So it pulled out the stops on a high voltage charm offensive.

Google has used its popularity with consumers as a carrot, offering key influencers a digital pulpit few others can match—the Google Hangout, a multi-party video-conferencing service that can also be broadcast.

Though Hangouts can be set up free of cost by any Google user, the service offered to ministers and politicians was supported directly by Google, with weeks of preparation beforehand.

The first person Google chose to do a Hangout with in August 2012 was Gujarat chief minister and BJP leader Narendra Modi. Drawing in tens of thousands of online viewers, the session was a resounding success. That made the job of convincing Congress politicians much easier, leading to Hangout sessions this year featuring union ministers Shashi Tharoor, CP Joshi, P Chidambaram and Milind Deora.

“It was the platform determining the speaker, and not the other way round,” says a senior industry watcher on the condition of anonymity.

On December 17, 2012, Anandan and Sibal stood next to each other while inaugurating chandnichowknowonline.in , a Google-created website showcasing over 2,500 local businesses in the busy Delhi area—Sibal’s constituency—each of whom had been provided a free website as part of Google’s outreach initiatives. Later that day, while inaugurating a data centre in New Delhi run by the National Informatics Centre, the minister would go on to say, “My dream will only come true when we will provide the people of India with that [Google] kind of platform.”

Google should be happy with that. As Balakrishnan says, “You’re living through the best years of Google. Every company goes through that.”

First Published: Jul 22, 2013, 06:12

Subscribe Now