IRDA Could Stifle Online Insurance Aggregators

Latest guidelines from IRDA threaten to further tighten the screws on web aggregators but they aren't rattled yet—after all, internet-savvy consumers are their insurance

Moneysupermarket.com, one of the UK’s most popular websites for financial services and insurance, doesn’t sell any products of its own. But it still made over £200 million last year, at a pretax profit margin of 32 percent. It simply re-routes the hundreds of thousands of online visitors and queries it gets to banks, insurers and financial service providers, in return for a fee.

Back home, Yashish Dahiya, 40, co-founder and CEO of Policybazaar.com, India’s largest internet-based insurance aggregator, wants to be the country’s equivalent of that.

A layperson might think he’s already done it. With an estimated share of over 90 percent of the market for internet-based sales of insurance in India, and revenues of Rs 65 crore for 2013, the five-year-old website seems to have hit the sweet spot. This, in turn, has allowed it to raise nearly Rs 70 crore in venture capital funds from Info Edge, Intel Capital and Inventus Capital over two rounds. “ICICI Lombard was the king of the online world. Today I sell 20,000 new policies each month while they sell less than 3,000, excluding travel,” says Dahiya. Those 20,000 monthly policies are worth over Rs 20 crore in premium, he adds.

“The online aggregation space is more or less a one-horse race led by Policybazaar,” says Yateesh Srivastava, COO of Aegon Religare Life Insurance.

Despite these affirmations, Dahiya finds himself running to avoid a bullet to Policybazaar’s head by way of the latest regulations from the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (IRDA) titled ‘Exposure Draft Regulations—Web Aggregators 2013’ released on July 21. Technically, the guidelines—currently in draft state—are meant to govern the seven licensed internet aggregators that operate in India. But they might as well have been called the ‘Policybazaar Shutdown Guidelines 2013’.

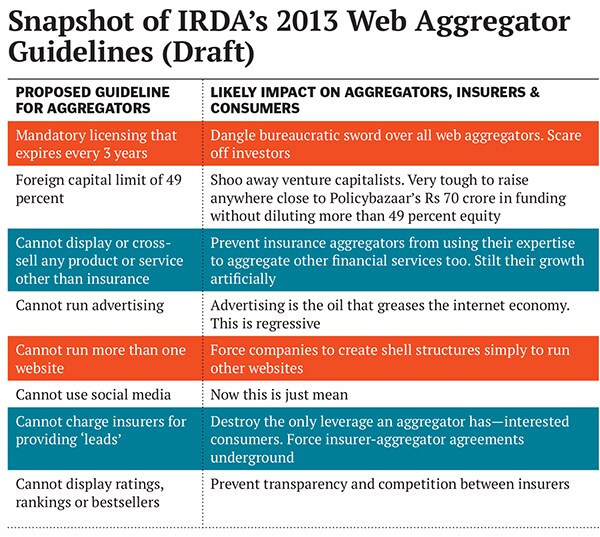

Consider their intent. From lead generation to advertising to cross-selling to comprehensive comparisons, the guidelines ban or scupper almost every globally-accepted way for insurance aggregators to make money. They mandate 50 hours of training and certification for every employee a compulsory licence that expires every three years a ban on operating more than one website and an outright ban on the use of social media.

If these weren’t enough to dissuade venture capitalists from investing in aggregators, IRDA goes on to limit foreign investment at 49 percent—the same as in the insurance space. “This clause wasn’t there in earlier drafts. It looks like it was inserted to prevent any of the aggregators from getting venture capital funding,” says Deepak Yohannan, founder and CEO of MyInsuranceClub.com, one of the six other web aggregators currently licensed and approved by the IRDA.

Dahiya, however, stays surprisingly sanguine. “I like to think of this as chemotherapy treatment. If it doesn’t kill us, it will kill the others [competitors],” he says.

REGULATOR, HEAL THYSELF

The first set of regulations nearly did kill Policybazaar. Released in late 2011, they cast the regulatory and licensing net on the entire web aggregator industry. Comparisons, ratings or rankings of insurance products were prohibited, as were advertisements. The maximum aggregators could charge for a lead was arbitrarily fixed at Rs 10.

“Like MakeMyTrip or Yatra in the travel space, we are a vertical search engine. Our competitor is Google. And if they can make Rs 100 per click through bids from various insurers, why can’t I? Imagine imposing a cap on what Google can charge,” says Dahiya.

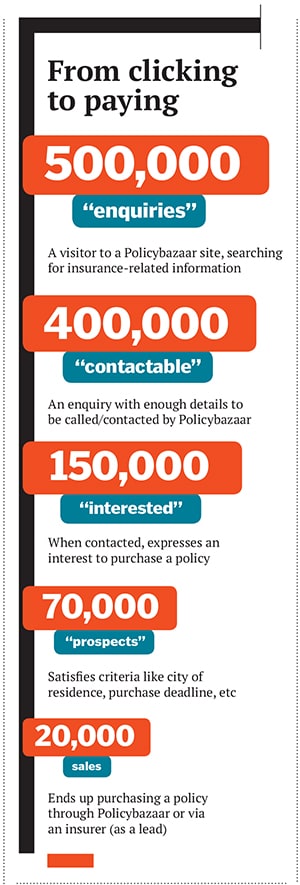

For leads resulting in sales, the commission fee was capped at 25 percent of what an insurer would pay any other distributor, broker or agent. Even there, Policybazaar and other aggregators say insurance companies don’t disclose which of their leads convert to sales, considering it proprietary information. “Of the nearly half-a-million enquiries on our site annually, around 60,000 people buy policies. But only around 20,000 sales are visible to us. IRDA hasn’t set up any mechanism to force insurance firms to be honest,” says Dahiya.Now, the IRDA had no reason or power to regulate websites that aggregate consumer enquiries and pass them to insurers who, of course, were regulated. And yet they did.

“They were wary of the internet. For some part, because they don’t know the channel and are afraid of this beast. For the other, because they’ve heard that over time the internet can dominate other channels, like in the UK, for instance,” says Yohannan. Nearly seven out of every 10 motor and household insurance policies sold in 2012 in the UK were bought online, according to Finaccord, a market research firm.

Emails sent to the senior joint directors—Suresh Mathur and BV Sastry—in charge of IRDA’s Intermediaries Department, and to the office of Chairman TS Vijayan went unanswered. But most aggregators consider the present chairman more pro-internet than his predecessor, J Hari Narayan.

“He [Vijayan] ran the IT department for LIC before becoming IRDA’s chairman, so he understands the importance of technology. I believe he’s told the industry that, in five to seven years, he expects 25 percent of the industry’s revenue to come via the internet,” says Yohannan.

The few silver linings that exist in the guidelines—aggregators can collect payments, send reminders and perform outsourced tasks for insurers—are attributed to Vijayan’s outlook. Even so, says Srivastava, “given how new ecommerce is in India, the regulator needs to get a better understanding of its dynamics”.

BOUGHT, NOT JUST SOLD

The biggest example of this lack of understanding is the industry and IRDA’s belief in the old adage: ‘Insurance is always sold, never bought’. The conventional view goes like this: The most profitable policies are sold most aggressively most consumers are gullible the regulator must protect them from being conned.

But, on the internet, those constructs are exactly the opposite. Consumers know what they want and are willing to research it consequently real-time and transparent competition ensures that the best-designed products are also the most sold.

“While brokers and agencies sell products that offer the highest commission, you’ll find that policies sold through insurer websites or by us are often the most competitive,” says Dahiya.

Take Aegon Religare, for instance. “We were the first to launch an internet-only product, iTerm [a term insurance product], in October 2009. The industry waited for a year to see how we fare. But, within no time, we started generating sales volumes of 2,500 to 3,000 policies per month, which were being bought voluntarily. Within a year, we saw the first competing product and now there are 10 to 12 similar products in the market,” says Srivastava. Today, Aegon Religare claims to generate 30 percent of its revenue via the internet. “Online term plans are growing at nearly 50 percent annually—the only segment that is growing in an otherwise slowing industry,” he says.

Meanwhile, the traditional channels of selling insurance are just not what they used to be. “For life insurers, almost all distribution channels have been disasters. Replicating LIC’s agent network is impossible because getting agents is difficult. No respectable chap wants to be an insurance agent today, when a mere knowledge of English can get you a job that pays Rs 25,000 monthly,” says Yohannan. “Most brokers, save a few, don’t want to touch the segment because the revenues generated aren’t enough to offset issues around training and retention. The only channels left are group and bancassurance, both of which squeeze them with exorbitant sign-up fees and commissions.”

R Jagannathan, managing director of Chennai-headquartered Star Health Insurance, agrees that the internet plays an increasingly big role in helping consumers take an informed decision. “While we do sell our policies online, I’m an old-timer in my belief that health insurance is still not bought, but sold, and through eye contact. Persuasion is essential because India hasn’t matured to the point that demand [not supply] runs the industry,” he says. Star Health generated around 5 percent of its ‘market’ revenue through the internet, he adds.

The kind of eye contact that Jagannathan refers to is becoming difficult to come by in big cities. In most cases, an agent must overcome a minimum of three barriers: The security guard, the intercom and the front door of a customer’s house before he even has a chance to sell a policy, says Yohannan. EVOLVING TO SURVIVE

EVOLVING TO SURVIVE

“The 2011 IRDA guidelines were designed to nip web aggregators in the bud. We sat through that, some of us aggressively and others quietly,” says Yohannan. In response to guidelines prohibiting comparisons or fair compensations for leads, aggregators started evolving complex and expensive workarounds.

“Because Policybazaar.com was not allowed to show comparisons, we started subsidiary firms and websites to do those. Remuneration was passed on to these subsidiary firms, much like what happens in ecommerce [due to FDI regulations] or education [due to a ban on profit-making],” says Dahiya.

The website AccurateQuotes.in was designed to do policy comparisons and hand back the results to the parent. Because it wasn’t worthwhile to pass along a good lead for a mere Rs 10, it started concentrating on converting those leads to sales itself.

If LIC had an advantage with its ‘feet-on-street’ agent model, Policybazaar poured investments into scaling its ‘bums-on-seats’ model. Its call centre staff of nearly 900 generates close to 80 percent of its revenue by selling policies over the phone. In essence, it morphed into a telemarketing-based insurance agent.

With the 2013 guidelines banning it from operating multiple websites, Policybazaar will need to evolve. “I’d like to think our business has three phases. The first was lead generation and advertising. The second was aided commerce [using a call-centre to sell policies]. The third will be unaided commerce where a customer can directly buy a policy from us online, but it will require big investments in branding and technology. We’re entering that space,” says Dahiya.

The way forward is to integrate with insurers’ websites and allow consumers to buy online, says Yohannan. But, he adds, “For the next 18 to 24 months you will need to provide assistance to online customers. For this, you need Policybazaar to build the market.”

Dahiya has a curiously pessimistic-optimistic view of the future, saying, “We are very happy with the new guidelines. No competition can come in now because no one can make money now.”

Meanwhile, Star Health’s Jagannathan offers a big-picture perspective: “There may be many avenues like agencies, brokers, corporate agencies, third party websites and company websites, but the ultimate objective should be to penetrate audiences and sell more insurance.”

First Published: Sep 13, 2013, 06:15

Subscribe Now