India's solar power punt

Despite corporate India's surge of enthusiasm in the solar power sector, ground realities pose major hurdles to the government's ambitious goal

In June 2014, Ashok Agarwal thought he was home and dry. Agarwal, the CEO of Essel Infraprojects, was on the verge of delivering the $5 billion Essel Group’s first solar power project—a 20 MW plant in Osmanabad, Maharashtra—within deadline. All that was left was putting up the last 10 km of transmission lines that would connect the Rs 200 crore-plant to the state electric grid.

And that was when Agarwal got a reality check: Farmers who owned the land on which the transmission towers were to be built refused to allow their construction. Essel had the necessary government clearances, and a lot was riding on on-time completion of the project. “We had to get the farmers together, literally touch their feet and beg,” remembers Agarwal, “Of course, we had to pay more money.”

It took three months to put up the last five towers over just half-a-kilometre, and Agarwal missed his deadline by six days, losing Rs 50 crore in bank guarantees. The next time around, he vows, he will set up the transmission lines first.

But this would not be the end of his struggle with farmers who own land. In Punjab, when he started buying land for a 30 MW solar power plant in Mansa, in 2014, he first got the land for the transmission towers. But then, he got stuck while acquiring land for the plant itself: Farmers who owned the land started holding out for higher prices. Agarwal had begun acquiring 150 acres at Rs 8-9 lakh per acre, but by the time he finished, he paid Rs 25 lakh per acre, making the project costs go haywire.

Land acquisition, a hurdle for all infrastructure projects, is turning out to be the biggest pain point—although hardly the only one—for the development of solar plants in India (generating 1 MW of solar power requires 5 acres of land over which the photovoltaic cells, or PVCs, are spread). And price is not the only issue. Land holdings are often small, and divided among several family members, with disputes arising among competing branches of the same family. For instance, Agarwal recalls 20 members of one family landing up for signing the deal for a single 5-acre parcel, with each member wanting a share of the money.

Government push

The stories that you hear from solar power producers are a far cry from the euphoria that seems to surround the recent statements and commitments made by some of the largest corporate houses in India towards the country’s solar power industry.

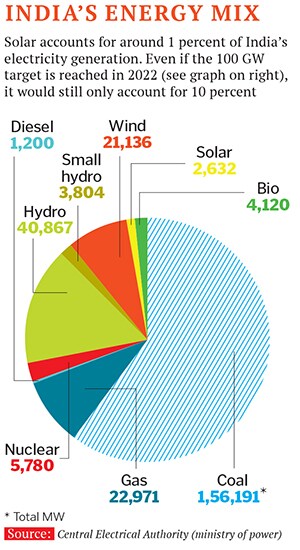

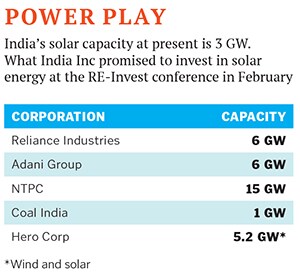

At present, India has just 3 GW of installed solar capacity, having added less than 1 GW in 2014. This accounts for just over 1 percent of India’s total installed capacity of 260 GW (as of January 2015), according to the Central Electrical Authority (ministry of power). To put India’s solar target in perspective: Germany, the world’s second-largest solar market (recently ousted from its first place by China), has just under 40 GW of installed capacity China has just over 40 GW the total global solar capacity is 360 GW.

Sixty percent of India’s installed capacity for electricity generation is coal-based, by far the biggest source of power. According to Amit Bhandari, a fellow at think tank Gateway House, “Even if India meets its 100 GW solar target by 2022, it would account for only 10 percent of the country’s energy needs.”

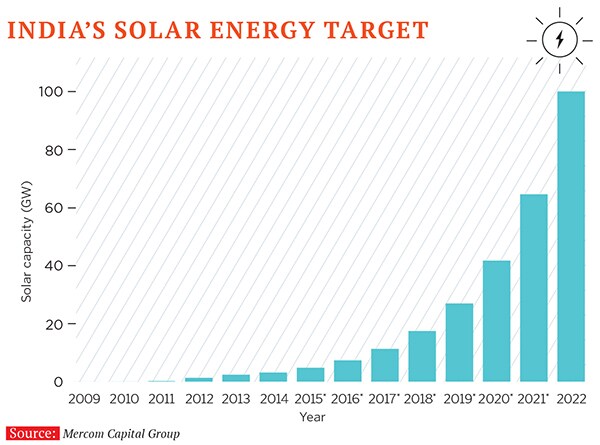

After the ministry of new and renewable energy (MNRE) revised India’s solar energy target in 2014—from having an installed capacity of 20 GW by 2022 to 100 GW by 2022—a host of corporate houses are signing Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) with state governments. For instance, Essel Group, which has put up 100 MW of solar power capacity, has said it will install 7.5 GW by 2022, a 75-fold increase. At RE-Invest (a renewable energy conference held in New Delhi this February), corporate houses, foreign solar companies and public sector corporations committed to install more than 200 GW by 2022.

However, nearly all the solar power producers, electrical contractors, project consultants and experts Forbes India spoke to find the figure to be far-fetched. Indeed, reaching even the government’s target of 100 GW will take a huge shift in policy and execution. “There is a big mismatch between the goal and the roadmap there’s no clear strategy,” says Tobias Engelmeier, founder and managing director of Bridge to India, a consultancy. “Hundred GW is too ambitious. We should see about 30 to 40 GW in India, which would be really good. That’s what Germany has done in 10 years.”

The government’s plan, however, is noble: India is a huge importer of energy (mostly fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas) and a shift to alternative sources is desirable. The country is blessed with an abundance of natural sunlight and solar power can be produced even in remote areas, through small off-grid solar plants that can power clusters of rural homes.

Ground reality

But can solar power go beyond localised production and usage, and compete, in any meaningful way, with conventional power?

Action on the ground is constrained by several factors such as land acquisition, poor evacuation facilities to transport the power to the state grid, low availability of PVC modules for solar panels and unwillingness of state power distributors (discoms) to buy solar power, which remains more expensive than coal power.

Where land is concerned, meeting the 100 GW target would require 5 lakh acres, or half the land of Goa.

“Land is the biggest problem for solar power,” says Anil Sardana, CEO, Tata Power, India’s largest integrated power producer, with a stated aim of producing 25 percent of its total output from non-coal and non-polluting resources by 2020. Yet, the company has gone slow on solar power. Its portfolio of renewable energy—it forms 14 percent of its current total output—mainly comprises hydro and wind energy. Sardana says that although Tata Power was one of the early movers in the solar energy sector in India—its oldest solar project, a 118 KW plant at Lonavla recently completed 18 years—it is unwilling to make the huge investments that rival companies seem to be making. “Making big bets on solar without land under your belt doesn’t seem right,” he says.

Developers also say that even if land is available, regulatory bottlenecks can prevent companies from buying large tracts and scale up rapidly. “Acquisition of farm land is an issue,” says Khurshed Daruvala, managing director of Sterling and Wilson, the electrical contracting arm of Shapoorji Pallonji Group, which provides engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) services for solar plant developers. “For example, the maximum farmland holding is 27 acres per farmer in Maharashtra. If you want to acquire 500 acres, the procedures for the company are long because you have to acquire each parcel individually.”

To work around the problem of finding large, contiguous land areas, wind energy company Suzlon is trying a hybrid model, of putting up solar panels in the spaces between its wind turbines, and leveraging on the common transmission and maintenance infrastructure. Chairman and Managing Director Tulsi Tanti, a wind power evangelist for more than a decade, says, “Though wind is a cheaper and proven technology, today, solar has the momentum.” Suzlon is finalising plans to put up 200 MW of solar projects in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat in FY16. Its plans have been boosted in no small measure by Dilip Shanghvi, founder and managing director of Sun Pharmaceuticals, and one of India’s richest persons who bought a 23 percent stake in the company for Rs 1,800 crore this February.

Essel’s Agarwal agrees with this hybrid model: “Solar gives you output in the day time while with wind, your output is generally higher in the evening.”

Another way around the land acquisition problem is the development of solar parks. In this “plug-and-play” model, state governments or EPC developers acquire the land, put up transmission lines, get the required government permissions and approvals, and offer the facility to companies who can put up their solar projects on the land and offer the operators a fee.

At present, Charanka Solar Park in Gujarat, with a capacity of 590 MW (of which 224 MW has been commissioned by 20 developers) is the only operational large-scale solar park. Bhadla Solar Park in Rajasthan is expected to be operational soon.

The renewable energy ministry has plans to set up 25 such solar parks (each with a capacity between 500 and 1,000 MW, or up to 20 GW in total) over five years. Consequently, several states are flagging off solar parks to attract investors. Among the biggest such projects is the Adani Group’s MoU with the Rajasthan government to set up a 10 GW solar park.

PVC problems

PVC problems

Other hurdles in the rush towards generating solar power include the technology and supply of PVCs, which make up 60 percent of the cost of a solar module. Rahul Gupta, founder of Rays Power, highlights the shortage of Indian-made solar panels: “The total capacity of cell manufacturing in India is only 700-800 MW. Compare this to one Chinese company, Canada Solar, which alone has a production capacity of 3 GW!” Gupta adds: “But despite this shortage, many PSUs like NTPC [which has committed to add 10 GW through solar projects] are insisting on using only Indian-made cells.” The government’s ‘domestic content requirement’ makes it a must for state-run solar power producers to source components from Indian manufacturers, who may not have the capacity or quality of foreign imports.

Indian manufacturers of PVCs have also been unable to compete with cheaper Chinese and Taiwanese imports despite government tariffs. The domestic market getting flooded with low-cost imports has plagued Indian companies such as Indosolar and Moser Baer, two of India’s largest PVC manufacturers. Both the companies had to shut down operations. But after the recent announcements, they are looking to restart.

However, all companies are not struggling. This January, Adani Enterprises signed an MoU for a joint venture with US solar company Sun Edison to set up “India’s largest integrated solar PV manufacturing facility” in Mundra, Gujarat, over the next four years. The facility would ease the shortage of India-made PVCs.

Maximising the performance of PVCs is also an issue. In January, Chinese cell-maker Trina Solar, a leading global player listed on the NYSE, released its latest models of cells, which offered an efficiency of 20.4 percent. This means that for every 1 MW of installed capacity, only 20 percent actually reaches the grid (compared to 60-80 percent per 1 MW of coal). This is higher than the efficiency rate of cells made by Indian manufacturers, which is between 16 and 18 percent. However, even the output of superior PVCs falls over time, due to the panels getting dirty, over-heating and general wear and tear. Essel Group’s Agarwal says the output of even the best solar panels falls by 0.8 percent per year, and so by its 25th year, a panel will operate at 80 percent of its original output.

Indian entrepreneurs also seem to be unwilling to try out new technologies, such as solar-concentrators that have higher efficiencies. Solar-concentrators work like magnifying glasses: Mirrors are spread over large areas and they focus sunlight on a water heater, which generates steam to power turbines that produce electricity. This method requires a large amount of land and the technology is still nascent.A lesser-known aspect of generating solar power efficiently is the need for large amounts of water the solar panels need to be cleaned in order to maintain power output. Project consultants Gensol estimate the cost of water infrastructure to be Rs 2.75 lakh for every megawatt of power generated in a solar park.

Bratin Roy, vice president, industry services, TÜV SÜD South Asia, says, “There is also an issue of water quality, because Indian water has high calcium content. This creates problems because it doesn’t clean the solar module properly and cuts panel efficiency.” TÜV SÜD is a German solar project management consultant, whose first big project in India was a 150 MW project in Dhule, Maharashtra, in 2009.

Low absorption capacity

Although Roy admits that there has been a buzz in the solar power sector over the past seven or eight months, he notes a key challenge: Evacuation. In many cases, state electricity boards are simply not buying power from solar plants. “On the transmission side, it’s important to make the grid available,” says Roy. “If you can’t take the power you’re generating, it’s a national loss and loss for the power company.”

For, even if the government ensures land and transmission lines, the customers in this case are India’s loss-making power distribution companies, which are already reeling under huge debts. Raj Prabhu, CEO and co-founder of Mercom Capital, a consultancy, says, “Look at the credit ratings of India’s utility corporations, they’re all junk. Every year, the government provides subsidies to utilities. When a bank lends you $100 million for a solar project and your customer is a utility with no credit rating, that’s high risk.”

The government has now mandated that discoms buy a fixed percentage of their required electricity from renewable sources (in what is called renewable purchase obligations or RPOs), along with power generated from coal. In 2013-14, the RPO was 7 percent in Gujarat and 4.8 percent in Delhi (it is pegged at 7.6 percent for 2015-16). However, neither Gujarat nor Delhi has met its targets, with discoms citing the high cost of solar power as the reason. But the price per unit of solar power has seen a rapid decline: Five years ago, a unit of solar electricity would cost Rs 16-17 now it costs between Rs 6.5 and Rs 7, thanks to the falling cost of PVCs. “Not many discoms are really excited,” says Agarwal. “Where will you absorb this capacity if there are no takers? Unless you have RPOs of 15-20 percent, which the government is talking about, it won’t happen.”

The government, despite pushing for the development of renewable energy, did not specify a roadmap to achieve its proposed targets in the Union Budget of 2015: The announcements of reduced taxes and increased buy-back rates made in the budget would have negligible effect on the cost of production. But Vineet Mittal, vice-chairman of Welspun Renewables, is confident of policy changes in the future: “Prime Minister Modi is passionate about clean energy. He understands the energy sector better than other politicians because he turned it around for Gujarat… The MNRE and Piyush Goyal [minister of state with independent charge for power, coal and new & renewable energy] were very scientific about this. They’ve been consulting us since July.” The Welspun Group has been one of the early movers in the solar sector and has pledged to develop 8.6 GW of solar power. The government has decided to revive the long-pending Renewable Energy Bill which will cover several aspects related to the generation and distribution of clean energy. Mittal believes the Bill, if ratified by Parliament into an Act, should increase RPOs to 15 percent and provide routes for financing, such as infrastructure funds and green energy bonds.

It is clear that the industry is looking for concrete plans. “With the 100 GW announcement, the government got a different set of people in the room: Everybody in the world is listening up,” says Engelmeier of Bridge to India consultancy. “It wasn’t the case at all for the last three years and it links to India being seen as a better investment destination.” Global investors like American firms Sun Edison and First Solar (which plans to develop 5,000 MW of solar power in India by 2019) are willing to bet on India’s domestic market by setting up manufacturing plants and creating thousands of jobs. Separately, financers ranging from the World Bank to private investors and clean-tech funds are lining up with cheap finance options.

At the retail level, medium-sized entrepreneurs like inverter makers and EPC contractors are entering the race dozens of firms offer a range of products for rooftop solar panels, agricultural and rural applications. The total installed capacity of rooftop solar power generation in India is 285 MW as of October 31, 2014, according to Bridge to India.

India’s push towards renewable energy has a lot going for it. It is a perfect story in many ways, one that allows every participant to bask in the glory of sustainability. Yet, there is an urgent need for a pragmatic view of this story one that goes beyond the talk.

First Published: Apr 23, 2015, 06:12

Subscribe Now