India's New Centre-State Equation

In the early days of nation-building, economic policy was dictated by Delhi. Now more and more states are taking charge of their destinies. In them, Delhi has the best chance of reclaiming India's gro

In January 2012, a few members from the Planning Commission landed in Thiruvananthapuram at the invitation of Kerala. The state planning board had also invited outside experts from within the state as well as other institutions such as NCAER (National Council of Applied Economic Research) and ICRIER (Indian Council for Research and International Economic Relations). As the meeting started, Planning Commission Deputy Chairman Montek Singh Ahluwalia began speaking about state planning.

According to a Planning Commission official present at the meeting, Chief Minister Oommen Chandy interrupted him: “We don’t want you to plan for us. We know what we need. What we want from you are the skills one needs to plan.” He then went on to elaborate structural problems Kerala faced. He told the Commission they’d be better off helping Kerala engage systematically with people and institutions outside its boundaries. He wanted them to help create processes to design plans.

Kerala is not the only state eager to learn. Early this month, Amit Mitra, finance minister to the West Bengal government, was in Delhi. He had met with Union Finance Minister P Chidambaram in the morning, given the customary bytes to the media, had lunch at Bengal Bhavan and was ready to leave for the airport. Just as he stepped into the car, his cellphone rang. It was his chief minister, Mamata Banerjee.

While Mitra was with Chidambaram, Banerjee was studying a file on a meeting to be held in Delhi the next day. Organised by the Planning Commission, it was a day-long conference of all state planning boards to share knowledge and initiatives. Bengal’s minister and secretary for planning were scheduled to attend.

Banerjee asked Mitra if he could stay back for a day and beef up the team at the conference. Bengal would present its achievements in overhauling public healthcare. Banerjee was keen that Mitra talk about e-governance and tax reforms too.

In the sub-text of these episodes is the changing texture of India’s federal fabric. “Economic freedom in the domains under the control of the Central government is stagnant. Perhaps it is even reducing. And issues under the domain of the state government are improving,” says Laveesh Bhandari, founder director of Indicus Analytics. That is reflected in what states are doing.

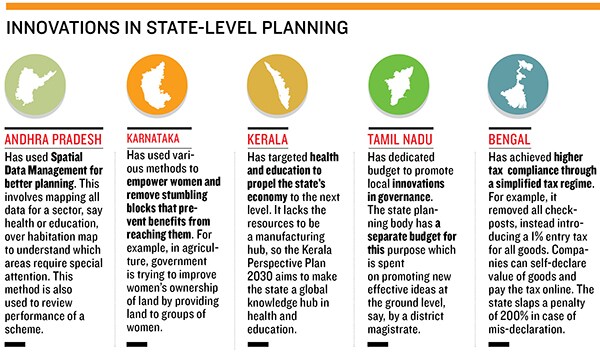

Kerala has prepared a 20-year roadmap with help from the Delhi-based NCAER to eventually position the state as a knowledge and services hub. The plan would be unaffected even if governments change. It has chosen the Nordic economies as its benchmark for human development and has set specific, measurable targets like “appearing in AT Kearney’s index of global cities by transforming Cochin into a global city”.

West Bengal is investing heavily in improving governance and making it easier to do business. “We have made the entire tax process electronic. No other state in India issues VAT [value-added tax] certificates in dematerialised form,” Mitra told Forbes India. What makes it urgent for him and the state’s chief minister is that in a ranking of Indian states on economic freedom, Bengal languished near the bottom in 2011, the year Banerjee came to power.The list, published by Cato Institute with Indicus Analytics and the Friedrich Naumann Foundation, provides evidence that even indolent states are waking up to competition. Gujarat replaced Tamil Nadu at the top. Himachal Pradesh and Haryana retained the fourth and fifth positions. Madhya Pradesh, a state rarely known for industry, jumped from sixth place to third. And Chhattisgarh, beset with Maoist insurgency, improved from 15 to 11. Even Jammu & Kashmir inched up a notch to number seven.

Gujarat is positioning itself as a manufacturing hub. It is already home to the world’s leading car makers and chemical industries. It is building a world-class road network to ease movement of goods and is positioned to make the most of the Delhi-Mumbai industrial corridor.

West Bengal grew at 8 percent in the first quarter of fiscal year 2013. Though growth has since slowed, the finance minister expects it to pick up again. Tax revenues rose 35 percent between April and September and the state expects to end the year beyond its targeted growth rate of 25 percent.

The Asian Development Bank gave Bengal a $400 million loan last year. But before that it laid down 16 conditions. “They cleared it because all the fiscal reforms they wanted were already done,” says Mitra.

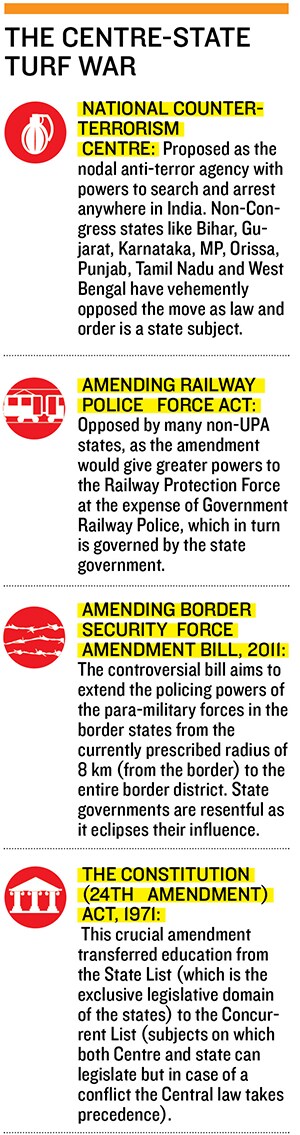

Despite many states becoming proactive and increasingly vocal on national issues, the Centre continues to act like the Big Brother. The debate over a common goods and services tax or GST is an example. The Centre gave up its rigid position only after three years of hard-ball with states.

Changing Narrative

In the first decade of the millennium, the India story was driven from Delhi. But that is changing. A group of relatively younger politicians in the states are becoming more comfortable in business suits. They understand the value of a promise and are rolling out the red carpet for anybody who can help create jobs, build infrastructure and add value to local economies.

“States have realised they can decouple from the government of India and still function,” says an official with a state planning board who has also been in charge of state finances in the Union finance ministry.

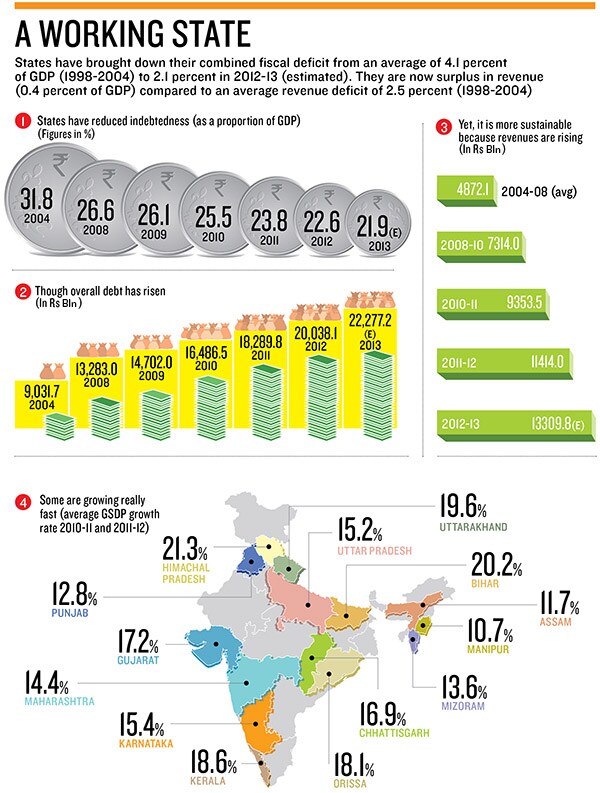

To put that into perspective, consider the following set of numbers.

The most visible face of state progress is Gujarat chief minister and prime ministerial aspirant Narendra Modi. He proved business-friendliness can erase the worst blots when the European Union ended its diplomatic isolation of the state since the 2002 communal riots. European diplomats hosted a lunch for Modi in Delhi in January to talk business. Not surprising because Gujarat has emerged as arguably the best destination for investors.

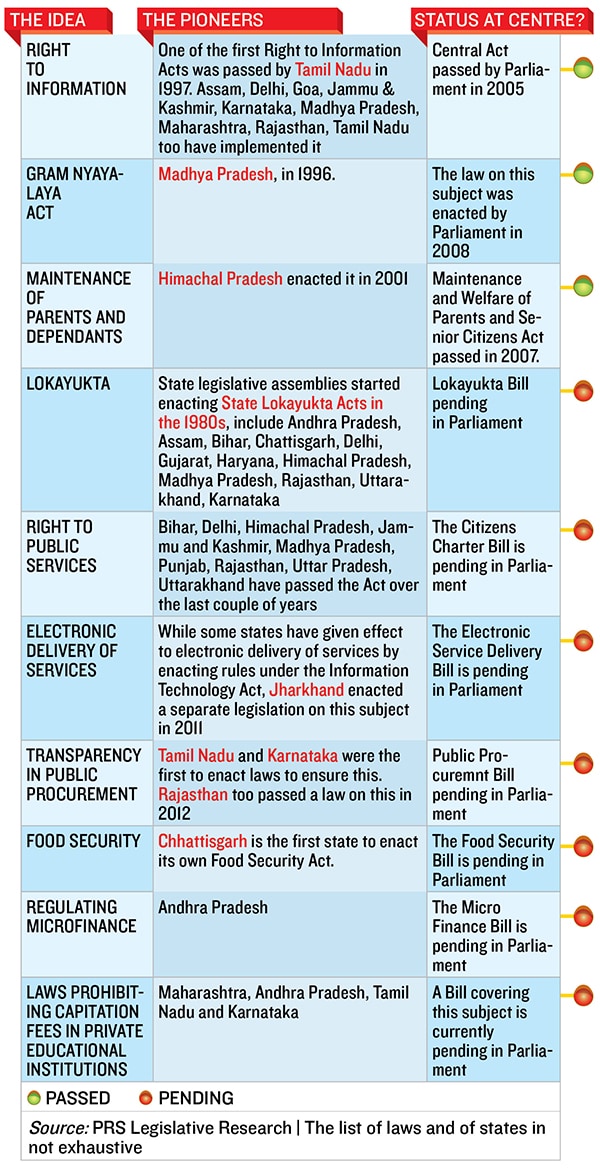

Others are now following Modi’s model of aggressively wooing industry and improving governance. Innovative ideas are pouring in. Bihar and Orissa have pioneered legislation to stamp out corruption. Karnataka is putting gender equality and women’s empowerment at the heart of planning. Kerala, as mentioned earlier, wants to be on par with Nordic nations. West Bengal now allows free movement of goods, having removed checkposts and trusting businesses to be honest. Punjab has introduced a Right to Services Act. The idea is to reduce citizens’ interaction with government officials and subsequently reduce the opportunity for corruption.

This is not to say that states are ready to become completely independent, like the United States of America. Some states are more competitive than others. As good as it sounds, there are implications as well that ought to be considered.

“It will be a strategy for higher growth. But it will also be a strategy for disparities between states and could possibly lead to conflicts. That’s the trade-off,” warns Amrita Dhillon, professor of economics, University of Warwick.

Fiscal and structural imbalances persist in the states. Even the reformers bow to treasury-bleeding populism. Punjab gives free power to farmers, including the rich ones. It has a poorly-implemented subsidised food scheme that is burning precious cash.

Karnataka gave such a free run to its mining barons that within a few years they amassed enough wealth and political power to sit in government, twisting and dictating policy to enrich themselves. The economy of the state’s mineral-rich districts lies in a shambles today.

Gujarat rolled out the red carpet for businessmen but ignored its poor human development indicators, such as health and malnutrition. Its tribal population is particularly vulnerable and the state has not done much.

Kerala’s economy is trapped in low productivity cycles and the government is stooping beneath debt. It cannot find jobs for its educated youth even as pension costs mount and inefficient companies suck up taxpayers’ money. Most states are also laggards when it comes to delegating decision-making to local bodies. “The closer we go to people the better will be the quality of delivery of services and governance. This would mean greater devolution from the Centre to the states and from the states to local bodies,’’ says KM Chandrasekhar, vice-chairman of Kerala Planning Board and former Union cabinet secretary.

Most states are also laggards when it comes to delegating decision-making to local bodies. “The closer we go to people the better will be the quality of delivery of services and governance. This would mean greater devolution from the Centre to the states and from the states to local bodies,’’ says KM Chandrasekhar, vice-chairman of Kerala Planning Board and former Union cabinet secretary.

Politics of Development

Elected policymakers always have an eye on the next polls when framing welfare policies. The consequence of this is opportunism clearly visible in programmes run from Delhi. That is why the number of programmes with the Centre’s stamp—such as job, health, housing and education schemes—is rising even as the party that runs the national government struggles to retain its influence in states.

Chhattisgarh Chief Minister Raman Singh told the National Development Council that an inclusive growth strategy will work only if states and the Centre work as partners. “The 12th Plan, like the previous ones, is built on a ‘patronage’ model and, therefore, is business as usual,” Singh remarked on December 27, 2012.

Congress leader and cabinet minister Veerappa Moily counters forcefully when he says that most states have a Janus-like approach when it comes to federalism. In their relationship with the Centre, they want independence. But when it comes to local bodies under their governance, states do not want to let go of powers. “The rules of the game have to be observed by all,” says Moily, who, as head of the second Administrative Reforms Commission (ARC), had suggested deep reforms in the governance machinery down to the last level.

He says many of the Central schemes would have performed much better if local bodies were formed and empowered. “What is wrong in giving money directly to panchayats or district councils? They are constitutional bodies.” The second ARC had said that a one-size-fits-all approach would not work. It suggested more involvement of states while designing schemes and flexibility for state-specific variations. Moily says the Centre is willing to make changes, but it is the states that are unbending. “They cannot ask for everything to be given in their hands as untied funds under the umbrella of federalism. Look at Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan. States are completely in charge. But not a single one has passed the legislation needed to implement it,” he argues. As They Saw It

As They Saw It

To understand how things have gotten here, an understanding of some history is important. The Cabinet Mission of 1946 formed by the then British government led by Clement Attlee had proposed a Central government with powers limited to foreign affairs, defence and communications. However, those who drafted the Constitution finally settled on a structure in which the Centre was more powerful.

In the early days of nation-building, it hardly mattered because almost all of India was ruled by the Congress. But in 1967, it lost several states to rivals. The Indira Gandhi years saw the Centre asserting itself and forcing its will on the states. Economic policy and planning was dictated by Delhi and it was expected states would implement them. The Centre kept a tight control over resources and investments. States ruled by rival parties often found themselves at the short end of the stick.

Gandhi’s frequent use of Article 356 to dismiss elected governments from the states and finally the imposition of Emergency in 1975 seriously dented the federal character of the country. But the rise of regional powers and the economic reforms of 1991 started to usher in autonomy.

“Our federalism has matured over the last 20 years,” says Jayaprakash Narayan, leader of Lok Satta Party and legislator from Kukatpally in Andhra Pradesh. “One of the main reasons is liberalisation and the other is the coalition culture and Delhi’s need for regional support.”

The shift to capitalism unshackled the states somewhat as public investments gave way to private capital that found its way into regions perceived as business friendly. “States could think of their comparative advantage and compete with other states [for investments],” says a state planning board official.

When the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance came to power in 2004, it again corrected course, leaning to the left and starting a slew of welfare schemes that encroached on states’ turf.

Often, states resent projects controlled from Delhi and would much rather decide what they ought to do in their own backyard. “The schemes that the Central government babus and politicians pride themselves on, the ‘favour’ of development they bestow upon the states, is actually the states’ own money! When Rahul Gandhi loftily announced in public meetings how much money the Central government has sent to Bihar, it is this money he is mostly talking about,” former Rajasthan Chief Minister Vasundhara Raje was quoted as saying by the Financial Express on June 10, 2011.

“Each such scheme has its own set of guidelines which are suitable for certain areas but cannot be applied in others,” says Chandrasekhar of Kerala Planning Board.

But things weren’t like this. In 2003, many states were running deep deficits. Treasuries borrowed to pay salaries and interest. That is when the Centre stepped in with fiscal responsibility agreements under which states had to commit to reduce deficits and improve revenues. The Centre would also help them replace costlier debt with cheaper loans.

“States learnt their lessons. It was hurting politicians to keep the treasuries closed for days together,” a former finance ministry official says.

The Centre and states perhaps co-operated because awry public finances threatened the fiscal health of the country. Besides, fixing the balance sheet rarely pays electoral dividends and hence is less likely to spawn quarrels over ownership.

Centre-State Friction

Sukhbir Singh Badal, Punjab’s deputy chief minister, told us earlier this year that states’ influence at the centre was directly proportional to its number of Members of Parliament (MP). “If you have 20 members in Parliament, they will receive you at the airport. If you have only five, no one will even ask after you,” Badal had wryly remarked.

One senior government official agrees there is strong reluctance at the Centre to give credit where it is due because of political rivalries. The Congress on its own is in power only in four major states, including Delhi, and four smaller ones. In seven states, it shares power with regional allies.

Often the branding and marketing of Central schemes create tensions. In July 2010, during Question Hour in the Karnataka assembly, Congress legislator N Sampangi demanded ambulances run under a Centrally-funded scheme, popularly known as ‘108 ambulances’, have Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s pictures on them. Minister B Sriramulu rejected the demand.

R Ashok and BN Bache Gowda of the ruling BJP threatened a dharna and demanded AB Vajpayee’s picture along the Golden Quadrilateral highway network, to claim credit for the flagship project of the previous National Democratic Alliance government led by the BJP. Pictures of the former prime minister were allegedly removed once the Congress came to power at the Centre.

States are also miffed at what they call lack of consultation on crucial policies. “The Constitution of India clearly defines the jurisdictions of Centre and the states. It is so clear there is no room for doubts regarding business of states and the Centre. But, in the recent past, the Centre has dominated the states and dictated them,” says Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chauhan.

Dhirendra Singh, former Union home secretary and member of Commission on Centre State Relations, 2010, says that it is difficult to segregate any issue—natural resources, education or health—between the three tiers of governance. “Each level has a role. It is a continuum.

In administration we follow the principle of subsidiarity. That is, let the activity be done at the lowest level at which it can be done efficiently,” he says. “While no one can argue with it, in actual terms it is exceedingly difficult unless people try to build consensus and minimise conflict.” The Opportunity

The Opportunity

The rise of the states presents a great opportunity for India to revive its flagging economic growth. Many are learning the value of accountability and responsible governance. It is perhaps time the Central government reviewed its relationship with them and how federalism is practiced.

For starters, it could implement the recommendations of the Rangarajan Committee on efficient management of public expenditure. One of its key suggestions is to route all Central funds through state treasuries. Currently, it transfers a lot of money directly to beneficiaries or societies created to bypass state governments.

“The situation is extremely confusing since a large number of Central agencies send funds directly to agencies in the state. We do not have a consolidated picture of how much money is coming where,” says Kerala planning board’s Chandrasekhar. “This makes planning difficult and effective monitoring more or less impossible.”

There is no real forum for discussion between states and the Centre. The National Development Council meetings are perfunctory and meaningless. The annual plan meetings that states have with the Planning Commission are ritualistic and chaotic as the chief ministers and their official entourage do the Delhi round.

Former UP Chief Minister Mayawati did not attend a single one during her tenure. Once when Vasundhara Raje, the then Rajasthan chief minister, came for the annual plan discussion, the Planning Commission suggested it would help with more funds if the state expanded the rather modest plan. According to a person who was present at the meeting, Raje refused saying the state was well aware of what it could and could not do.

Such meetings may soon end, though the top-level discussion between the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission with chief ministers would continue. There is entrepreneurial energy in the states and a perceptible sense of purpose in many administrators. “They are now engaging in a systematic way with people outside to create processes,” says Planning Commission member Arun Maira. “We are managers of these processes from which plans will emerge.” He says the Commission will replace annual state plan discussions with focussed subject-specific meetings involving all states and the Central ministries. The Centre is also putting in place a transparent information management system to monitor cash flows.

The states are at an inflection point and perhaps present the biggest post-liberalisation opportunity for economic growth. The 12th Plan is just beginning and Finance Minister P Chidambaram will present the first budget of the Plan period on February 28. It could perhaps begin by recognising that each state is beset with unique issues and the solutions have to be bespoke. Some players in the orchestra are performing well. It is up to the conductor to help others lift their performances too. But the conductor seems to be preoccupied with the audience rather than getting the symphony going.

First Published: Feb 27, 2013, 00:00

Subscribe Now