How the Rise of Third Party Marketplaces can Alter Indian E-Commerce

Why most of India's biggest ecommerce companies want to become third-party marketplaces. And why a few are choosing to sit it out

Vijay Sales, a privately-held electronics retail chain that started out from Mumbai in 1967, is an unlikely poster child for the next phase of ecommerce in India. Most Mumbaikars swear by its product range and deep discounts. “But who walks into stores anymore?” most armchair ecommerce diehards are likely to retort. They may even view Vijay Sales, with its 50-odd stores and over Rs 1,500 crore annual revenue, as a ripe fruit waiting to be digitally disrupted by the likes of Flipkart. But over the next few months, many leading ecommerce companies, including possibly Flipkart itself, are likely to be courting Vijay Sales instead of figuring out how to steal its sales. âž¼

“Over the last 12-18 months there has been a maturing of suppliers, from electronics retailers like Vijay Sales to brands like Samsung and Benetton. They are now willing to invest more time and effort so that a product that was earlier going from Vijay Sales to Flipkart and then to the consumer, can now go directly to the consumer,” says Alok Mittal, managing director of venture capital firm Canaan India.

The mega trend that is sweeping across the ecommerce landscape, that could turn Vijay Sales and Flipkart from competitors to partners, is the rise of “third-party marketplaces” (3P)—ecommerce platforms where retailers and brands can sell to customers directly.

In Chennai, Sathish Babu, the founder and CEO of Univercell, a 450-store mobile phone chain that claims to be doing over Rs 1,000 crore in revenue, is being wooed too.

“We’ve been approached by Flipkart, Amazon and many others to join their marketplaces,” he says. Though Univercell has been selling phones online for the last seven years, the volumes weren’t all that big because their focus was on store sales. But that will change with the entry of marketplaces, says Babu.

“While marketplaces may seem only evolutionary from the consumer end, at some level it could be revolutionary from the supplier side,” says Mittal.

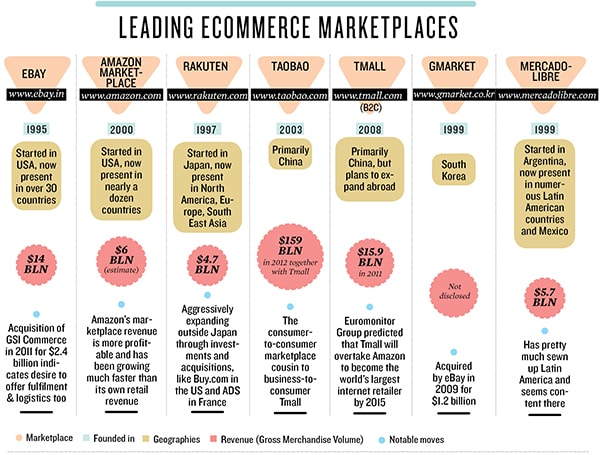

Ecommerce marketplaces aren’t a new concept. eBay has been running exactly those since 1995 inter-nationally and since 2005 in India.

And while eBay has been successful in India, its scale has been dwarfed by the runaway success of inventory-led “first-party” (1P) ecommerce sites like Flipkart, Jabong, Myntra and Homeshop18 (disclaimer: Homeshop18 is part of the Network 18 group that also publishes Forbes India) who burnt through tens of millions of dollars in venture funding to offer customers a more easy, predictable and consistent experience.

Some of those companies now reckon Indian consumers are ready for a better alternative to eBay: A “managed marketplace” where they control the marketing, look and feel, logistics, shipping and customer service, leaving only sales to third-party sellers. eBay in contrast adopts a more hands-off approach on those counts, letting suppliers figure out their own respective strategy for each.

“India has nearly 35 million SMEs who are not able to leverage the power of the internet because they lack the critical mass to attract customers online. If marketplaces can harness them, this would be the second coming of ecommerce in India,” says Sanjeev Aggarwal, co-founder and senior managing director at Helion Venture Capital.

The Lights at the End of the Tunnel

Why are so many ecommerce companies hitching themselves to the marketplace model so rapidly? To understand that, imagine them crossing a long, dark tunnel at the end of which lie untold riches.

They see a light at the end of the tunnel, the marketplace model, which allows them to scale sales dramatically by becoming the platform where millions of buyers and sellers meet and transact. Each sale leads to a fat commission ranging from 6 percent to as high as 20 percent of its overall value. A lot of this can go straight to the bottom line because significantly less of their cash needs to be used up in marketing, fulfilment (the need to stock inventory to better fulfil orders) and customer service.

“The shift to marketplaces is a positive sign for Indian ecommerce. In the present model where the cost of operations is high, unit economics don’t necessarily lend themselves to scale. So the more you grow, the more you can lose. Marketplaces will allow platforms and third-parties to jointly solve for scale and thus shift focus from valuation to sustainability,” says Muralikrishnan B, the country manager for eBay India.

Marketplaces are the dominant ecommerce life forms across most countries in Asia. For instance, Alibaba’s Taobao and Tmall marketplaces account for 90 percent and 51 percent of all consumer-to-consumer (C2C) and business-to-consumer (B2C) ecommerce in China. eBay-owned marketplaces Gmarket and Auction together control 70 percent of South Korean ecommerce. In Japan, Rakuten has a share of nearly 30 percent of all ecommerce.

In most big countries in Latin-America, the largest ecommerce player is MercadoLibre, again a marketplace. In the US, eBay is of course the largest example, but even Amazon’s revenue mix is rapidly shifting towards its marketplace: Though it accounts for only around 9-12 percent of the company’s overall revenue, analysts estimate that it makes up 40 percent of Amazon’s gross profit. Moreover, its marketplace business is estimated to be growing at 80 percent annually versus 30 percent for its direct ecommerce retail.

Naturally, Indian ecommerce players too are making a beeline for this ‘light’. But there’s another reason for their collective sprint: The other light at the end of the tunnel, from the oncoming train called ‘cash-burn’.

Most large ecommerce companies have spent tens of millions of dollars—in a few cases, maybe even hundreds—as they sought to build the fastest, cheapest, safest and most technologically advanced alternatives to physical retail.

Using the template provided by Flipkart (which itself was largely channelling Amazon), venture-funded ecommerce companies in India realised around 2009 that the reason consumers hadn’t taken to online shopping even after a decade was because there were serious bottleneck issues that needed to be solved first-hand, instead of by a partner.

The lack of reliable logistics and delivery partners meant most players set up their own warehouses across the country, backed by in-house last mile delivery networks.

To foster long-term trust, they set up their own in-house customer support organisations, manned by dozens or hundreds of staff. To get around customer’s unwillingness to transact online using their credit or debit cards, they introduced and turned Cash-on-Delivery into the default payment mechanism. To reduce the time it took to deliver a product to a customer, they decided to buy and hold their own inventory, instead of sourcing it after a sale had happened. And finally millions of dollars were spent on marketing—across TV, newspapers and the internet—to constantly remain in the minds of potential customers.

None of the above could be funded from their revenues, because no one was generating any profits. It was venture capital all the way.

But during the last two years most of that has withered away, thanks to a limping domestic economy and even worse global outlook. Many ecommerce players have either closed down or have sold themselves for peanuts in equity, having failed to raise additional funding. Others are existing as zombies, unable to grow because of lack of capital, meekly hoping for a miracle in the form of a foolish buyer.

Moving to a marketplace model is thus about survival too.

Which is not to say marketplaces cannot throw up newer opportunities as well. For instance, there is almost zero marginal cost for today’s ecommerce players to offer the so-called ‘long tail’ inventory (niche products that are bought by very few, and very infrequently) in a marketplace model. Fatter profit margins from third-party seller fees can be used to organically fund the expansion of their own first-party offerings, instead of using equity or debt. And perhaps most importantly, companies like Flipkart and Jabong that have spent tens of millions of dollars building their proprietary logistics and delivery organisations can finally make money from them by getting marketplace sellers to pay for using them.

Risk and Tumble

In spite of the mad rush to open marketplaces, not all leading ecommerce companies believe India is ready for this.

Mukesh Bansal, the founder and CEO of Myntra, India’s largest online apparel seller and one of the top three ecommerce players, is one of the naysayers.

He says, “Ecommerce companies like us are still refining our solutions to basic problems like product selection, delivery and customer service. In product selection for instance, we think people want a great selection and not just a random assortment of ‘long tail’ products. While the sector is still building trust with customers, I hear delivery times in marketplaces vary from one week to one month, resulting in anywhere from 5-20 percent orders getting cancelled because suppliers are not able to supply products. So, we see marketplaces as a distraction for us in our category, but we may consider it in a few years if by adopting it we can offer better choice for consumers and improve their experience.”

Rushing headlong into a marketplace model is fraught with risks, especially in a market where ecommerce acceptance is still nascent.

“In the US, retail evolved from small mom-and-pop stores to supermarkets to television buying to the internet over a period of five decades. In China that happened in two decades. In India I feel we’re trying to do that in two years!” says Sundeep Malhotra, the CEO of Homeshop18, who is also a marketplace sceptic at present.

Homeshop18 has decided against the marketplace route in India because Malhotra feels the level of maturity that is required from consumers, vendors and logistics partners is yet to be seen.

The biggest impediment, he says, is unreliable third-party logistics and the complexity of cross-state barriers. “In a small country like South Korea you can ship any product to any place in less than 24 hours. In a large country like the US you can build a hub-and-spoke logistics infrastructure that will allow you to stock products across the country, so delivery can be hastened. But in India, poor surface transport and a myriad of taxes on inter-state goods transfers makes logistics really tough,” he says.

The biggest challenges will crop up within hybrid 1P-3P businesses, for instance like Flipkart and Jabong, where the platform will both co-operate and compete with sellers. Amazon is the only leading marketplace globally where this conflict exists and controversies keep flaring up every now and then.

In essence this means the same company is both a market maker as well as a marketplace. When a customer searches for a particular product that happens to be in stock with both the platform owner as well as multiple third-party sellers, who gets selected as the default ‘Buy from’ option can have an enormous impact of sales.

“The DNA for fulfilment [own inventory] and marketplaces are very different so you should pick one, but not both. Otherwise there could be channel conflicts between the platform and the merchants, both of whom are competing for customers,” says Aggarwal.

Amazon’s marketplace sellers allege that the company observes best-seller trends from its marketplace partners, and then uses the data to offer the products directly to customers for a larger share of the revenue.

The skills required to handle these issues—tact, trust-based partnerships, transparency and open conversations—have not hitherto been required at either Flipkart or Jabong, both extremely young, aggressive and impatient organisations. But if they want to become default platforms that sellers trust and use repeatedly, they will need to acquire those skills.

Then there are conflicts that will pop up within all marketplaces, including pure play ones like eBay, Snapdeal and Shopclues.

For instance, thanks to a surfeit of suppliers and excess inventory, prices for any product will tend to fall till they’re close to what would be marginally profitable for a small retailer. In other words, the end of Maximum Retail Price (MRP). This is a good thing for consumers, but really bad news for brands.

A brand like Samsung may wake up to find that its current Galaxy series flagship phone, the S4, is being discounted and sold way below MRP and even MOP (Market Operating Price, the minimum price suggested by brands) by some marketplace sellers.

In the 1P model it could arm-twist the seller into obeying its pricing diktats under the threat of being cut off from future supply. But in a marketplace model it will find its powers significantly diminished because many of the smaller sellers may have got their stock indirectly from the market.

Things are made even tougher because “India has the maximum number of distribution partners in the world, from C&FAs [Carrying and Forwarding Agents] to wholesalers to distributors to stockists to retailers,” says Malhotra.

Of course, it stands to reason that the platforms themselves are going to be unwilling to penalise their sellers all too often for offering lower prices to consumers.

There will also be numerous disagreements between platforms and sellers around 1) delivery timelines (which will be worse than current 1P ones) 2) the fee charged for using in-house fulfilment (versus other third parties like Aramex or Blue Dart) 3) who bears the responsibility and cost of returns and 4) how customer feedback might be used to incentivise or penalise sellers.

“Compared to an inventory-led model where you have better control over the customer experience, there is a risk of slipping delivery service levels when you’re depending on someone else’s fulfilment capabilities in marketplaces. Two ways to solve this problem are through adequate screening of merchants, and in some cases running a ‘managed marketplace’ as an interim step where you collect goods from merchants beforehand and ship them directly to customers,” says Aggarwal.

Last Marketplaces Standing

“My sense is there will be room for two-three large marketplaces in India, with each developing in its own unique way. The race will be to become one of the top three,” says Aggarwal.

That sentiment is echoed by Mittal, who says, “The notion of a ‘land grab’ is even more applicable in the marketplace than inventory-led model, because it is inherently based on network effects. In the traditional ecommerce model a Goibibo was able to come in much later than MakeMyTrip but still gain market share, but that won’t happen in marketplaces where you need a large base of suppliers and customers. Thus, while it’s easy to think of, say, 50 successful inventory-led ecommerce companies five years down the line, there may not be more than five marketplaces. In some senses, it is a winner-takes-all model.”

Evidence from most large ecommerce markets around the world, especially from Asia and Latin-America, suggests that the top two to three players end up controlling 60-80 percent of the overall marketplace volumes. And while there may be many other marketplaces in the fray, their volumes are merely a fraction of the leaders’.

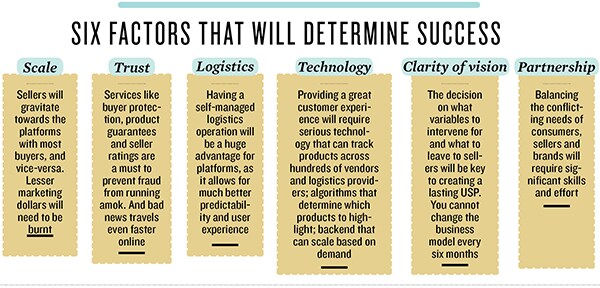

To understand who are likely to be left standing when the dust settles down in a few years, it pays to know what the determinants of success will be.

Because the marketplace model is a self-reinforcing one where scale begets additional scale, there will be a premium for those firms that are already market leaders in ecommerce today and can thus organically draw suppliers to their platform.

Equally important would be the quality of a marketplace’s logistics infrastructure. In country after country, from China to Japan to the US, the trend that’s clearly emerging is that for ecommerce to operate smoothly and efficiently, a marketplace needs to roll up its sleeves and handle critical logistics itself.

The best example of this internationally is Amazon, whose logistics efficiency is the stuff of case studies. In contrast, traditional marketplaces like eBay, Japan’s Rakuten and Latin-America’s MercadoLibre were known till recently as logistics-light platforms where sellers were usually responsible for getting their products into buyers’ hands.

But even that is changing. Some of the most strategic acquisitions made by these players in recent years—GSI Commerce by eBay in 2011 for $2.4 billion and Alpha Direct Services in France by Rakuten in 2012—are attempts to build their own logistics and fulfilment arms.

Finally, marketplaces are based on an underlying assumption of trust. To maintain that, platforms will need to do a fine balancing act between making payments and orders easier while attacking fraud and poor customer service.

It is here that eBay has an advantage, having fine tuned its fraud prevention, customer feedback and proprietary payment protection systems over the years. Its newer competitors will need to go through their own learning process—including errors— before they can replicate that intelligence.

Though eBay India does not disclose its revenue, it claims to have 10 million monthly visitors buying 13 products every minute on its platform from over 30,000 sellers. Industry observers and competitors alike attest to the fact that eBay has over the past few years significantly ramped up its scale and operating infrastructure, so it is almost surely going to be one of the marketplace survivors.

Among its newer competitors, the best placed on paper are Flipkart, Jabong and Snapdeal.

Both Flipkart and Jabong are aggressive, deep-pocketed and popular, so are likely to lead from the front as marketplaces take root among consumers.

“While we won’t hold inventory for marketplace orders, we’re still doing a managed marketplace where we will provide marketing, logistics and delivery, including pick up, packaging and delivery of items ordered,” says Mukul Bafana, one of Jabong’s managing directors. (Flipkart refused to participate in this story.)

Snapdeal is interesting because the company pivoted to a pure marketplace model early last year after abandoning its earlier premise of being a ‘deals’ site. In early April the site raised $50 million in its third round of funding, including from eBay. It even recently introduced TrustPay, a buyer protection plan much like eBay’s PaisaPay.

Other smaller or lesser known marketplaces, like Shopclues or Tradus for instance, will need to spend much more time, effort and money to position themselves as an alternative to their better known peers. It helps that Shopclues raised $10 million in series B funding in March this year from Helion and Nexus Partners. That’s not a patch on the money being raised or spent by its larger competitors, so Shopclues will need to be creative in its approach too.

An outlier worth watching would be Infibeam, an ecommerce player whose strategy seems to defy most standard models. It started out as a traditional ecommerce retailer then launched a web-based software platform called Build A Bazaar that can allow any retailer to offer ecommerce services through its website and is now transitioning into a hybrid 1P-3P model itself.

Vijay Sales, the electronics retailer mentioned at the beginning of this story, uses Infibeam’s solution to power its own ecommerce store.

Infibeam’s grand strategy is to get its hooks into independent retailers and SMEs across India and help them sell their inventory from either their own websites or Infibeam’s website. Conversely, Infibeam allows inventory belonging to one seller to be made available as ‘virtual inventory’ that can be sold by other sellers or Infibeam itself. “Anyone can sell anything from anyplace” would be a good way to describe the model, provided Infibeam can attract enough scale to its platform.

“We call our model a mix of distributed fulfilment and distributed selling,” says Vishal Mehta, Infibeam’s founder and CEO.

But the final arbiter of how marketplaces will work will be the Indian consumer. She has demanded a lot before loosening her purse strings online—free and fast shipping, cash on delivery, superb customer service and cut-throat prices.

“Our plans for the marketplace are only constrained by the customer experience we can guarantee. If that experience isn’t right, the model breaks down because you promised convenience and ease but are unable to deliver them. And because India is still nascent when it comes to logistics and delivery, you can’t guarantee the same quality between your order versus your partner’s,” says Bafana.

First Published: May 13, 2013, 06:23

Subscribe Now