Gurgaon: How not to Build a City

Gurgaon boasts of MNCs, swanky apartments, golf courses, and malls. Yet, water shortages and poor sewage disposal and public transport haunt the city

Without a doubt, Gurgaon is the kind of city urban planners can learn from on how not to build a city. This, for various reasons: A private sector gone berserk because it was blindsided by greed, successive governments that abdicated responsibility, and apathy on part of the landed gentry.

Once upon a time, travelling to Gurgaon from Delhi was considered a trip to the boondocks. Car maker Maruti’s plant aside, there was nothing there worth writing about. Then something happened.

KP Singh, the chairman of DLF, invited Jack Welch of General Electric (GE) to visit India. In his biography, Singh talks of a meeting he organised between Welch and Sam Pitroda, Jairam Ramesh and Montek Singh Ahluwalia. Soon after the meeting, in 1996 Welch gave GE the green light to set up Genpact in Gurgaon. In turn, this lured other multinational companies. What was once known as Guru Gram started its transformation into Millenium City.

Gurgaon was attractive to them because of its proximity to New Delhi and the international airport.

“Gurgaon today has the highest number of professionals per square inch in the country,” points out Atal Kapoor, an architect and one of the founding members of I am Gurgaon, an association focussed on improving the quality of life of its residents.

Today, Gurgaon houses practically every big name in the corporate world. Its buildings are designed by the best architects from across the world. Gurgaon has more than 20 outlets for luxury cars such as BMW, Audi and Volkswagen. Malls that stock practically every international brand dot the landscape.

The National Capital Region Planning Board, a body that overlooks planning for regions surrounding Delhi, had forecast that by 2021, Gurgaon would have a population of 16.5 lakh people. That number will be breached this year, nine years ahead of projection.

That explains why Ramaswamy R Aiyer, one of the most respected names in water management in the country, sounds acerbic. “Gurgaon is a disaster, a horror story of how urbanisation should not happen. It is not merely Gurgaon—little Gurgaons are emerging all over Delhi. When these monstrosities were being ‘developed’, did anyone think about where the water for them would come from, and where the waste generated by them would go? Now they exist and answers have to be found. I have nothing to say except to say that this isn’t development, but mal-development.”

His sentiments are echoed by Pramod Bhasin, non-executive vice-chairman of Genpact, India’s largest BPO. “There was a chance to build world class infrastructure and it wasn’t that difficult either. We could have built Singapore. But we didn’t.”

“The problems are clear if you sit here long enough. The roads here used to be dug up every six months…. I’ve seen buildings come up along with pastures where sheep grazed. It was inevitable our offices would collide with the lives of those who lived here in the villages,” he laments.

But research by PropEquity, a firm that researches property markets in India, throws up an interesting paradox. Between 2006 and 2011, as many as 35,353 new dwelling units were created. In the next three years, they predict almost one lakh units are being planned at an average price of Rs 4,500 per square foot.

The paradox is amplified by Bhasin’s sentiments. “An average Delhi resident sneezes at Gurgaon. But I look at them and say you live in a mess and pretend you’re better off because I’m far away from Delhi. But the quality of life is better here. The restaurants, the bars, the golf courses, the clubs are better here.” So much so that when a new expressway connecting Delhi with Gurgaon was opened, the concessionaire who built the road broke even within five years. Thanks to the projections, though, their concession period lasts all of 25 years.

Then, on the other hand, there are migrant labourers, domestic help and industrial workers who constitute Gurgaon’s poor. With no access to public transport, they resort to sharing auto rickshaws or comply with taxi drivers who flout norms and stuff as many as 10 people into a single cab. Their children often fall into bore-wells laid by citizens. These wells were dug because the government is in no position to guarantee water supplies.

The truth lies somewhere in between these extremes. People aren’t willing to let go of Gurgaon simply because there is no alternative. Gurgaon attracted them because property could be bought with money on which they had paid taxes and titles were clear. In Delhi, the costs were prohibitive and when affordable, the titles were disputed.

Who is in charge

of Gurgaon,’ is a question that could qualify for Kaun Banega Crorepati,” says KC Sivaramakrishnan, an expert on urbanisation from the Centre of Policy Research. His question comes from the fact that there are multiple entities that hold responsibility to develop the city. There is the Haryana Urban Development Authority (HUDA), private builders and a newly set up Municipal Corporation. Each has its own zones to manage. The problem with this approach is that implementing a holistic plan for Gurgaon has become nearly impossible.

Incidentally, the Corporation, which held elections for the first time last year, is yet to be allotted an office. Corporators say this is because the chief minister’s office does not want to cede control. “We have repeatedly told the mayor and the chief minister we want an office. But they want everything to be controlled from Chandigarh,” says a corporator who spoke off-the-record. The chief minister’s office did not respond to queries.

What exists now is a situation where only a third of Gurgaon is connected to a sewerage line. But residents who live in private colonies say HUDA officials turn their complaints down, arguing sewerage lines are the responsibility of private builders. Some builders have taken the onus of building sewage treatment plants and facilitating water supplies with private tankers.

But a World Bank official who does not wish to be identified says Gurgaon was nothing but a land grab operation by builders and politicians. A 2009 WWF Report on Indian Urbanisation quotes Arun Maira, member of the planning commission and part of a local NGO trying to revive Gurgaon. “The fundamental problem here is that urbanisation has been driven by bad planning and a thought process which doesn’t believe in devising viable urban spaces.” The philosophy, he says, seems to be to let people build residences and offices arbitrarily and as they get occupied, infrastructure and other economic activity will follow. This is a prime example of ad hoc and unsustainable urbanisation, he adds.

He points to the fact that huge tracts of land were given to private developers in Gurgaon. “These developers, over time, appropriated most designated green spaces and public spaces and extracted as much revenue as they could out of the land. So a city was created, but the opportunity of setting new benchmarks in civic life was lost.”

The pre-condition was that the developers would build the infrastructure to support these entities. Sensing potential, real estate firms like DLF, Unitech and Ansals moved in early. The builders allege development charges collected from them towards providing for infrastructure were diverted. “More than Rs 12,000 crore was collected and made available to the state government. But all this money has been used up by politicians in their constituencies. Nothing flows back into the city,” says a senior executive with a prominent real estate company who did not wish to be identified.

So how did things come to such a pass? Thirty-seven years ago, legislation was passed that allowed the private sector to play a major role in real estate development. The Haryana Development and Regulation of Urban Areas Act, 1975, encouraged the private sector to develop huge land parcels and build apartment blocks and office complexes.But the land they acquired was meant for agricultural purposes. When builders sensed the opportunity was right, they’d go to the Town and Country Planning Department and get a Change in Land Use (CLU) issued.

Col Sarvadaman Oberoi, one of the prominent activists in Gurgaon, says the Town and Country Planning department which directly functions under the chief minister, went out of its way to accommodate these requests for CLUs. “The apartments have come up wherever the builders got land cheap. Thus Gurgaon grew in bursts and not to a plan.”

Souro Dyuti Joardar, who retired from the School of Architecture and Planning in Delhi, says, “Private developers built residential complexes at locations where they could assemble land from the market through negotiations with local landowners…. Thus there has been sharp leap-frogging of development with vast patches of undeveloped land lying in between private colonies and the rest of the developed city.”

The free hand given to private builders came under fire recently after the Competition Commission imposed a fine of Rs 630 crore on DLF for abusing its dominant position and issuing contracts that were one-sided. DLF declined to comment.

The outcome of this haphazardness can be seen in various quarters. Take power, for instance. In 2002, Haryana had transmission and distribution losses of 38 percent. Ten years down the line, they’ve managed to cut it, but only to just about 25 percent. “The situation is so bad that the top officers at the power distribution company cannot even transfer a lineman without coming under political pressure. Illegal connections thrive,” says an executive from the Confederation of Indian Industries (CII) who did not wish to be identified.

“Our focus now is, how do we cope with this,” says Bhasin. “We provide our own security, our own transport, power, education and training. At some point I feel like telling them to give the city to us and we’ll run it,” he adds.

“After all, we get the city we deserve… They’ll gripe for a while, but then you can pull down the curtains and there are few things a good drink will not help you forget,” chuckles KC Sivaramakrishnan.

According to Sudha Yadav, the BJP MP from Gurgaon from 1999 to 2004, the polling percentage in the heart of corporate Gurgaon was as low as 7 percent in 2004 and 26 percent in 2009. “People have to give their time too. Money alone doesn’t solve issues,” she says while explaining why Gurgaon continues to be a political nobody in Haryana politics despite being hugely influential in terms of finances.

But there are signs of strong civil society action with people taking to the streets. In Gurgaon, becoming an activist and fighting for their entitlements is not just borne out of the need to contribute to society but is also driven by the realisation that unless they fight for their rights, those in power will never listen to them.

So they petition, make regular visits to the HUDA office and slap Public Interest Litigations against authorities for not taking action against illegal wine shops that have come up all over Gurgaon. They organise tree planting programmes and cleanliness drives and campaign for women’s safety. The people organising these programmes are bankers, architects, doctors, IT professionals and businessmen.

“They [HUDA] have barely managed to provide infrastructure for the existing residential areas. Why should anyone take their word that they would provide for the new areas that are being developed?” asks Sudheer Kapoor, who manages the DLF Residents Welfare Association.

Kapoor is the man people in the area turn to when the taps run dry or have to battle related problems. He arranged for air-conditioned bus services after he heard several people complaining they were cut off from the heart off the city and had no means to get to a hospital or a mall if their driver was unavailable or their car broke down.

However, the officials in charge of the administration in Gurgaon say there is no need for worry. “Tell me where in India do you not have problems pertaining to water? Things will fall in place,” assures superintending engineer VK Gupta at the HUDA office. The administrator in charge, Praveen Kumar, points out that requests have been made for additional water from the state pool.

Elsewhere in the district, in Manesar, where the authorities are planning to build new townships, a four-year-old girl died after she fell into a 70-feet borewell. The body was recovered only three days later as the local administration had to seek help from the Army who in turn had to call for tunnelling specialists in order to reach the girl.

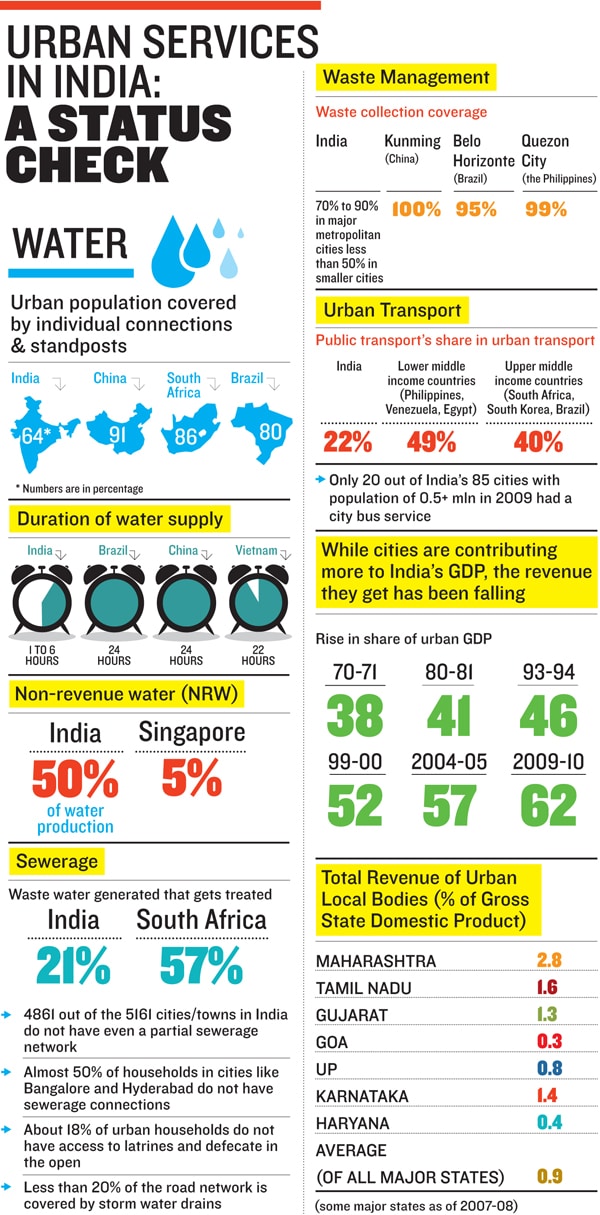

This urban chaos is not limited to Gurgaon. It is an indicator of everything wrong with Indian cities. A study by consulting firm McKinsey in 2010 argued that if India doesn’t get its act together on urbanisation, by 2030 the quality of urban services across cities will dip quite sharply. In particular, existing inadequacies in the water supply will increase by 3.5 times, in sewage by 2 times, in public transport by 3 times and the unmet demand for affordable housing will touch 38 million people. “The way things are going, 80 percent of Indian cities will end up going the Gurgaon way,” says Shirish Sankhe, director at McKinsey.

The worrisome part in India, says KC Sivaramkrishnan, is that Gurgaon is being seen as a role model for urban development. “But what is urbanisation if it is not about sustainability and planning and a better quality of life? Gurgaon is an excellent example of money spinning private real estate development free from all principles,” he says.

Shailesh Pathak, president of SREI Infrastrucure Finance and a former IAS officer, gives a good example of what ails in Gurgaon, or for that matter in many other cities in India.

HUDA has started construction of a road across Gurgaon, called Dwarka Expressway, joining Dwarka, in Delhi and Manesar in Haryana. The total construction cost of the road is just Rs 75 crore. But it translated into real estate collectively appreciating by around Rs 10,000 crore on properties along the road. “Most of this land is bought by private developers who are unlikely to plough back the profits into Gurgaon—something HUDA could have done had it developed the area itself,” he says.

But not all is lost for Indian cities. Most experts agree that if there is political will and greater autonomy for city officials, a city can be turned around in 10 years time.

“Do you know that just about 20 years ago, residents of Metro Manila used to store water in swimming pools?” says Seetharam Kallidaikurichi Easwaran, director of Institute of Water Policy and an Urbanisation expert at the Lee Kwan School of Public Policy. “Now, there is no need.”

There are numerous cities across the world like New York, Manchester, Bilbao, Tokyo, which almost died before being re-built. But it takes will and leadership.

First Published: Aug 02, 2012, 00:12

Subscribe Now