Direct Cash Transfers: What Money Can Buy

Will direct cash transfers empower the poor or push them towards wastage?

“Lottery si lag gayi [it’s as if I have won a lottery],” says Nagina, a beneficiary of the Delhi government’s Annashree scheme, which gives poor families without access to ration shops Rs 600 a month, no questions asked. This is the difference between the subsidised price of food sold through ration shops and the market price. Nagina earns barely Rs 3,000 a month, working in a readymade garments factory, and lives in a small 100 sq ft room in north-east Delhi’s low-income Sunder Nagri locality, which is only slightly better than a slum. She now spends Rs 16 every day to buy half-a-litre of milk she used to buy only Rs 5 worth of milk earlier. And she’s arranged for her daughter to take private tuitions.

Nagina, once a mere statistic on the government’s poverty tables, is now an empowered consumer. She has choice. Because she has more money in hand. Thanks to Nagina and others of her ilk, the polarised and acrimonious debate on cash transfers in India is set to move out of the theoretical and academic domain, where it was playing out till recently, and into the world of empirical evidence.

Statistical evidence from three pilot studies and anecdotal evidence from the implementation of the Delhi government’s Annashree scheme show that cash transfers give people choices which they never thought they would get. And yes, there is an example of a not-so-successful experiment—that of the cash reimbursement of kerosene subsidy in the Kotkasim block of Rajasthan’s Alwar district. But that’s another story, with different lessons.

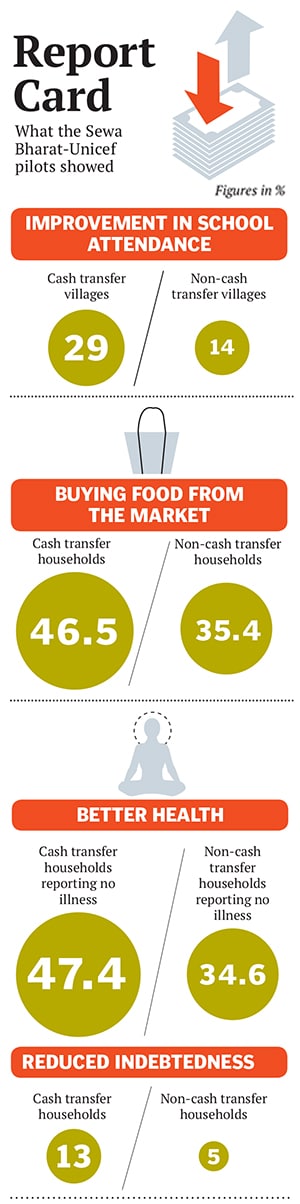

Preliminary findings by Sewa (Self Employed Women’s Association) Bharat, a trade union of poor self-employed women, and Unicef on unconditional and universal cash transfers in 22 villages in Madhya Pradesh were recently presented at a conference in Delhi. Every adult in 11 villages got Rs 300 and every child Rs 150 a month from June 2011 to January 2012. How they used this money was then compared with the spending by people in 11 other villages, which did not get the cash transfers.

The results will come as a shot in the arm for the UPA government, which is using cash transfer to get voters to the polling booth in the next elections. For Montek Singh Ahluwalia, deputy chairman of the Planning Commission, the two big takeaways from the pilot projects are that cash transfers can be done and that people don’t waste the money—two criticisms levelled by sceptics.

The findings showed that when people were given regular monthly cash grants, they did not fritter it away even when there were no conditions. Instead, education got top priority, people ate better food, spent more on medicines and invested in improving their livelihoods, buying sewing machines or farm inputs. Savings increased, debts decreased and the proportion of underweight children declined. Another smaller cash-for-food pilot, also by Sewa Bharat in 2011, in one low-income Delhi locality—Raghubir Nagar—presented a similar picture. In this pilot, families got Rs 1,000 a month for one year but their ration cards were suspended for that period.

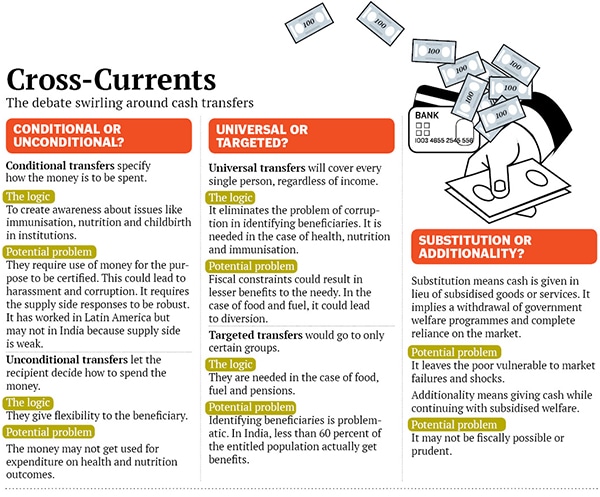

Interestingly, while cash transfers in India have been pilloried as part of a ‘neo-liberal’ agenda of market fundamentalists, some of the largest transfer programmes globally have been implemented by socialist governments—notably in Brazil and South Africa—and the intellectual argument in its favour has also come from left-of-centre theorists.

Research purists agree that these findings are broadly in line with the international experience of cash transfers being game changers for the poor. “Whether it is building household income in the short-term or breaking the inter-generational cycle of poverty, cash transfers have benefits,” says Lise Grande, resident representative of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in India.

So are cash transfers the next magic bullet? Don’t burden it with that expectation, says Bharat Ramaswami, professor, planning unit, Indian Statistical Institute.

Cash transfers have just one purpose—putting money in the right hands. “The principal aim of cash transfers is to support the income levels of the poor,” says Ahluwalia.

Put that way, it’s a trifle hard to argue with the logic of this alternative method of delivering welfare. Economist Jean Dreze, who’s known as a cash transfer sceptic, said in an emailed response that he’s only opposed to “an evangelical belief in cash transfers as a general answer to problems that may have better answers”. He favours cash transfers in some contexts like social security pensions for widows and the elderly as against giving them food. Cash, he points out, “is a good tool of redistribution within the household—it enables old people and widows to have some money of their own to spend on their own needs. Food, on the other hand, would just go into the family pot.”

A range of benefits flows from the one-point objective of cash transfers: Spending on education, food and health. The family of Lakhina, from Madhya Pradesh’s Jagmal Pipalya village, started eating rotis with dal and vegetables twice a day. Earlier, it was dal during one meal and vegetables during the other. In Delhi’s Raghubir Nagar, Neela, an Annashree scheme beneficiary, finds she no longer needs to borrow money for treatment if a family member is ill. It would be a tad simplistic, however, to argue from this that cash transfers have a decisive impact on malnutrition. “Malnutrition is the result of a complex set of factors. Food is just one of them,” cautions Grande.

And far from being a disincentive to work—one of the apprehensions about cash handouts—Grande points out that it actually enables the poor to invest in their livelihoods and take risks. Dara Singh, the sarpanch of Ghodakhurd village in Madhya Pradesh, got a group of villagers to use part of the money they got to form a fish farming co-operative. Radha, from the same village, also used the money to buy better quality seeds for her small farm and also took a loan to buy a goat.

The increased economic activity that this and the higher demand for food, education and health services generate helps stimulate the local economy as well. Ghodakhurd, for example, no longer has to deal with just one grocery shop it has two more now.

Leveraging of money takes various forms, as a Delhi-based think tank, Centre for Civil Society (CCS), saw while implementing a school choice voucher programme in east Delhi’s Seelampur area. Poor families were given four vouchers of Rs 1,000 each, which they could use to pay fees in budget private schools. Parents started negotiating with schools to waive the Rs 500, which they had to pay out of their own pocket, or to get belts and notebooks for free. The schools agreed since they were assured of regular and timely payments they normally faced a fee default rate of 30 percent a month. “It was an outcome we never anticipated,” says Parth J Shah, CCS president.

Don’t the poor squander money on non-essentials? In Sunder Nagri, Gudiya probably reinforced this belief when she spent Rs 3,000 she got under the Annashree scheme on buying a room cooler. She got a lump sum of Rs 7,200 for one year. “Cash transfers are spent on their intended use when people are sure the money will come regularly. When payments are irregular and lumpy, it will get spent on things that may appear wasteful,” says NC Saxena, member of the National Advisory Council.

In Raghubir Nagar, where also payments came bunched up but in smaller instalments, families used the money to buy food in bulk. Kavita Srivastava of the Right to Food Campaign echoes Saxena. “Poverty is a situation of need, not greed. There will always be an immediate demand for something other than food.”

Gudiya can’t understand the objections to her cooler. “This is also important,” she says, pointing out that her six-year-old son now slept well and did not fall ill as frequently as he did last year. Grande understands. “The point we are making about cash transfers is that poor families have precisely the same right to make rational decisions and choices as other economic actors.”

What’s particularly striking is that the poor are using the money they get to decisively reject the shoddy goods and services that the government throws their way and to shift to other options. The residents of Raghubir Nagar were unhappy when the 2011 pilot ended. During its duration, they didn’t have to make frequent trips to the ration shops for sub-standard food that was often lower than their entitlement. “We would go to the market and buy whatever and however much we needed,” says 55-year-old Bachchu, a hawker. When the pilot ended, they had to return to the ration shops, since they couldn’t afford the market price.

It is this that worries critics of cash transfers, who fear that it could become a justification for the state to outsource its welfare responsibilities to the market. “There is a dangerous illusion in India that cash transfers can dispense with the need to achieve a major expansion of public services, especially in the fields of health and education,” says Dreze.

This is in marked contrast to the experience of other countries, especially in Latin America, where cash transfers have increased the demand for health and education and this has, says Grande, prompted governments to up their game on the supply side. Dreze and Srivastava are particularly concerned that cash transfers could be used to substitute the PDS. “There is a system of checks and balances in a government system. How can a private vendor be held accountable?” asks Srivastava.

“No one is talking about replacing PDS overnight,” counters Ramaswami. Cash transfers, he notes, provide an alternative. “Leave it to states to choose the delivery mechanism.” The Delhi experiment—where subsidised grains under PDS continue for those in the below poverty line (BPL) category and with Antyodaya Anna Yojana cards, while the Annashree scheme benefits the poor who don’t have ration cards—is a good example. The scheme is to cover 200,000 families and has reached 80,000 families.

Ahluwalia favours an approach where the PDS remains but ration shops sell food at the economic cost and people are free to go to whichever one they want.

The Madhya Pradesh pilots did not study the substitution effects of cash transfers (the cash was an addition to subsidised welfare services). This is necessary, says Saxena, before drawing policy lessons from it. The Raghubir Nagar pilot was a substitution experiment but was too small to influence policy. The Kotkasim pilot, which attempts substitution, hasn’t worked very well. Those entitled to subsidised kerosene buy it at economic cost from ration shops and are reimbursed the subsidised amount. This limited sales to only genuine users of kerosene as a cooking fuel since the money went directly into their bank accounts. Kerosene sales went down and this was seen as ending diversion. However, there have been cases of genuine users being pushed out of the subsidy regime due to administrative and technical glitches.

“Substitution is a big issue and needs to be tested carefully to see if people are as well off if they are given cash or receive subsidies,” says John Blomquist, lead economist at the World Bank’s social protection unit. Different target populations, he says, may need different approaches. “There is virtually no country in which it is an either-or phenomenon. Often, it is a mixed approach to give cash where it is possible to do so and provide limited, subsidised services in certain circumstances.” Brazil’s Zero Hunger project, for example, combines cash handouts with public works, distribution of vitamin supplements and subsidised canteens, among other things.

Perhaps the most decisive vote for cash transfers comes from those who were part of the Sewa pilot in Raghubir Nagar and who are not entitled to the Annashree scheme because they have ration cards. “Why can’t we also get Rs 600 a month?” asks 65-year-old Neela.

First Published: Jul 03, 2013, 06:26

Subscribe Now