Realty's big-brand theory

Take a crowded market, depressed sales and high-involvement products, and the formula is self-evident. The days of commodity selling in real estate are over: Buyers are seeking credible, quality names

“If you had met me three years ago, I was a completely different man. I would say I was extremely confident,” says Harresh Mehta, 56, founder of Rohan Lifescapes, a real estate company that deals with redevelopment in South Mumbai. At the time, his decision to build Trump Tower on Hughes Road in South Mumbai had made him newsworthy. The limelight didn’t shine for long, though. Due to a slow economy and numerous delays in getting government clearances, Mehta decided to opt out of the project. Eventually, Trump tied up with Lodha Group to set up the now under-construction Trump Tower at Lower Parel.

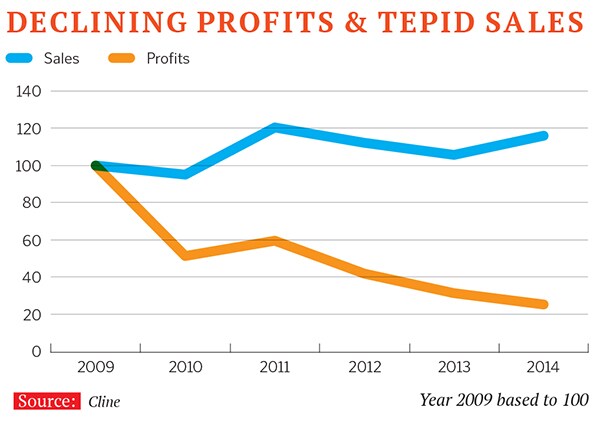

Mehta’s diminished confidence is a reflection of the state of his industry. Like others five years ago, he had assumed the upward trajectory of the real estate business. He is among the many who have been proven wrong. Residential sales were at a three-year low in the second half of 2014 across six cities (Mumbai, Delhi-National Capital Region or NCR, Bengaluru, Pune, Chennai and Hyderabad) in India. New launches were down by 28 percent compared to the previous year. According to Knight Frank, a real estate consultancy, 2.34 lakh units were sold in 2014 compared to 2.84 lakh units in 2013. And, since December 2014, there has been a marginal improvement but no fundamental change in the sales trend.

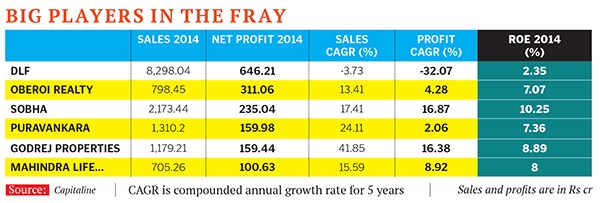

But there are those who have managed to buck the trend: Companies like Lodha Group, Prestige Estates, Godrej Properties, Tata Housing and Mahindra Lifespaces. These are the players whose properties command a 20-30 percent premium over those in the surrounding area. Consider that over the last three years, the overall sales of the industry went down by 20 percent annually. During the same period, Prestige Estates grew by 18 percent, Godrej Properties by 40 percent and Mahindra Lifespaces by five percent. Lodha Group, which is not listed, says it grew by 17 percent every year.

Apart from this growth in the time of gloom and doom, here’s another thing that they have in common: They have become trusted brands.

What’s in a name—that’s one question no upscale buyer, particularly in Mumbai, clearly India’s trendsetting hub in real estate, is asking anymore. For those who’ve not kept up with the evolving landscape over the last decade, the answer is, quite simply, ‘a lot’. Brands today account for around 50 percent of the total sales in the industry, based on data provided by listed companies. Also, most of these companies have not limited themselves to the premium and luxury segments they prefer to have a presence across the real estate market.

Quite clearly, long treated as a commodity by the sellers, property is increasingly getting the differentiation the buyers deserve. This focus on the brand is now a ten-year-old story in Mumbai, and the last 4-5 years have seen the trend spread beyond it, to cities like Bengaluru, Chennai, NCR and Pune.

While some players like Lodha and Oberoi Realty are pure real estate companies, the others (Godrej, Mahindra, Tata) are established and respected corporate brands which have extended themselves to the real estate business. Other real estate companies like Puravankara, Sobha Limited and Raheja Developers (belonging to Navin Raheja from Delhi) are quickly following suit, especially in markets like NCR and Bengaluru, because corporate brands appear to sell easily on the quality perception.

In some cases, the leadership of these ‘new-age’ real estate firms is also significant. Take the Lodha Group which—with a turnover of Rs 7,519 crore, it is the second-biggest real estate company in the country—is headed by Abhishek Lodha, and Godrej Properties, with a topline of Rs 1,179 crore, which is helmed by Pirojsha Godrej. Both are in their mid-30s, workaholics and are trying to create a sustainable model that defies traditional norms of the real estate business in the country. They understand the volatility in the market and take comfort from the positioning of their brands. They may have inherited ready-made brands but they have also, over the last five years, worked to make these brands the face of the real estate industry.

Yes, there’s a lot in a name. And here’s why.

“The market has suddenly turned. It has become a buyers’ market due to oversupply. This was not something that we had ever seen. We had only seen buyers coming to our offices… we never needed to make that extra pitch. A brochure was good enough. They came and purchased the flats that we built,” Mehta says with a touch of nostalgia. Though more optimistic about the market now, he knows he too will have to spend on brand creation. Because the industry can no longer survive on word-of-mouth publicity and local brokers.

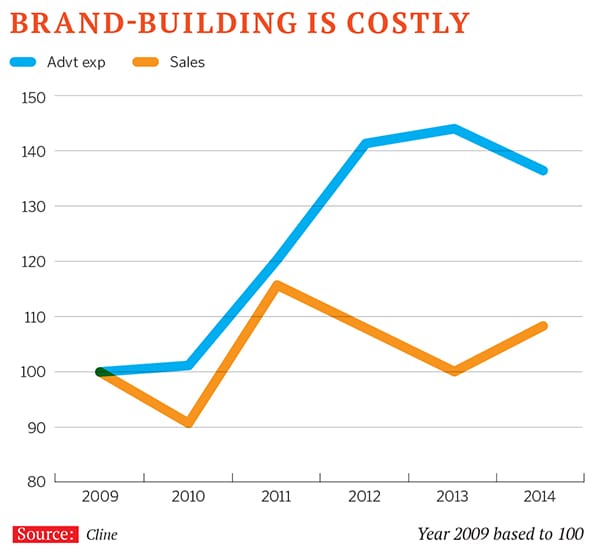

In recent years, advertising and marketing expenses for the real estate industry have been on the rise. Builders are ramping up their sales force and even hiring from top B-schools. Over the last five years, Godrej Properties saw its marketing and sales team grow from five people to around 100. Lodha Group hires around 20 people from premium B-schools every year. Plus, overall advertising expenses are not restricted to the newspaper space and television they also include social media. Since 2009, advertising and marketing expenses for the industry have risen by six percent while total sales are up by two percent for the branded industry players. Compare this to the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) industry where growth in advertising as well as in sales have been in tune at 15 percent for the last five years. “There are two key points of difference between the FMCG and real estate sectors. Buying an FMCG product is a consumption decision whereas housing is an investment decision. Housing is a far more deliberate decision which requires a whole lot of work,” says Joydeep Bhattacharya, head, consumer products and retail practice, Bain India.

Real estate players have no choice but to differentiate themselves to attract the buyer. “It is a market that has created an excess supply where the demand is slow in some segments,” says Niranjan Hiranandani, 65, managing director of Hiranandani Constructions. Since the time he built Hiranandani Gardens in the Powai township in Mumbai 30 years ago, he has concentrated on creating distinctive buildings and an atmosphere that will attract buyers. He provided amenities that included parks, swimming pools and state-of-the-art sewage treatment plants. “We never carved our journey to become a branded builder. We only wanted to build great structures. But over the years, the journey was such that we ended up where we are. We became a brand,” he says. And he isn’t exaggerating: The towers of Hiranandani Gardens in Powai define the area’s skyline.

Thirty years into its journey as a construction company, Hiranandani can comfortably command a premium on its name. But for many others, the brand-building exercise has only begun.Real estate developers, till a decade ago, were not thinking of lifestyle products. A stray example in Mumbai was Taj Wellington Mews at Colaba, created by Indian Hotels Company Ltd (IHCL) in 2003 as a super-luxury housing project—largely for serviced apartments. Over a period of time, with land values going up, product specifications started improving with higher costs. For projects in the Rs 50,000-Rs 60,000 per sq ft range in Mumbai, where land value was 70 percent of the total cost of the project, builders started thinking about investing in better specifications to create a much higher category of housing.

The first example of this shift was seen in BeauMonde (2008), built by Sheth Developers in Mumbai’s Prabhadevi area, followed by Lodha Bellissimo (Mahalaxmi) and Ashford Casa Grande (Lower Parel) during the same time. This was followed by Shapoorji Pallonji’s The Imperial in Tardeo.

Builders started factoring in additional features—think double-glazed windows and centralised air conditioning— to create luxury and branded products.

The impact of this change started to be felt at the demand end in Mumbai. Consumer preferences started shifting very quickly. Buyers started comparing prices and specs of builders and projects. If a developer was setting up something next to Lodha Bellissimo, he had to create something better.

Planet Godrej, for instance, was the gold standard in the Mahalaxmi-Parel belt since it was set up by Godrej Properties in 2005. It was also the tallest building in the area. “I think it was that building that redefined the skyline of the Lower Parel area as it was the first big project in that market,” says Pirojsha Godrej, managing director, Godrej Properties. “When it was completed, it was the tallest building in India with 51 floors at that time and gave us a huge foothold in the market.” Planet Godrej sold at a premium for a long time but, now, the adjacent luxury development by K Raheja, Vivarea, with its improved and higher-end specs, is selling at a higher price.

The search for the right value has also added to the ‘branded homes’ concept. American realty brand Trump Towers and designers Jade Jagger and Armani were brought in by the Lodhas because of the growing exposure of Indian buyers to global brands this was also motivated by the anxiety of developers to provide products that justify a Rs 50,000 per sq ft price when others were selling at a 40 percent discount in the same location. When Lodha launched The Park at Lower Parel in 2013, it sold at Rs 25,000 per sq ft. However, it still felt it wasn’t getting the desired value. Hence, a Trump Tower was added as international brand value to its portfolio.

Mumbai may have jumped on to the brand-wagon seamlessly but branded properties is an idea whose time has not yet come to complete fruition in some other centres. Specifically, the national capital.

On March 31 this year, Delhi-based Raheja Developers announced a Rs 100 crore-pricing for a six-bedroom penthouse on the 60th floor of its Revanta property in Sector 78, Gurgaon. In a project where the maximum price of an apartment is Rs 6,500 per sq ft (as given on the project’s website), the developer decided to offer a penthouse at Rs 1 lakh per sq ft. Despite its Versace association, this expectation invited ridicule from analysts and industry watchers.

Surabhi Arora, associate director-research at real estate consultancy firm Colliers International, says the perception of luxury is different in the NCR market. “If I had Rs 100 crore in NCR, I would buy a house in Lodhi Estate (central Delhi) and not a penthouse in Gurgaon,” she says. “A Rs 100 crore-flat on the top floor of a high-rise appeals to buyers in Mumbai. But here, people prefer bungalows in central locations.”

At the same time, Arora says that Raheja is probably just testing waters. “I think it is more of a trial to see the market response to a Rs 100 crore-flat,” she says. Anuj Puri, chairman and country head of Jones Lang LaSalle (JLL), says it appears to be more of a marketing gimmick.Raheja refused to comment on the story, but sent out a press release which said: “While residential prices upwards of Rs 1 lakh per sq ft are not unheard of in Mumbai, it is for the first time in Delhi-NCR that a developer has broken this ceiling.”

Raheja’s approach to differentiate its brand by staking claim as the first developer to price a house at Rs 1 lakh per sq ft is symptomatic of a me-too approach towards branding by developers in NCR. And, as Gaurav Mittal, managing director of Gurgaon-based CHD Developers Ltd, puts it, a cookie-cutter model to branding will not work. “You need to understand that there is a basic difference between the Mumbai and Delhi markets,” says Mittal. “In Mumbai, flats work for everyone because there is limited space. But in Delhi it is usually the middle class which buy flats. The rich prefer villas or farmhouses.”

Like their counterparts in the Mumbai market, real estate companies in NCR have also tried to stand out from competition by partnering with global brands. Noida-based Supertech has partnered with Disney India, global design firm Yoo Worldwide LLP and Armani/Casa, the home and interior design division of the Armani Group, for some of its projects 3Cs has joined forces with Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts for branded residences in Noida and BRYS has partnered with Italian interior design firm Tonino Lamborghini Casa for a project in Noida.

But can global brands attract buyers? Vineet Relia, managing director of SARE Homes, believes that developers have pursued brand differentiation without keeping in mind the people who buy their homes. “A buyer in the NCR market is not brand-conscious and is looking more for value-for-money homes. When a developer partners with a brand, the ticket price of the apartment goes up. This is not good because buyers here want affordable homes,” Relia says.

Armani/Casa will design the interiors of 100 luxury residences in Supertech’s Supernova project in Sector 94, Noida. The homes are priced between Rs 25,000 and Rs 30,000 per sq ft. RK Arora, chairman and managing director of Supertech, knows that his buyer pool is very limited. “If there are 100 buyers, I would say only 4 or 5 will buy these luxury residences. The demand in NCR is more for affordable homes,” he says.

JLL’s Puri says branding works when the developer knows how to extract the best from a partnership. “It is not just about attaching a famous name to a property. It is also about the value addition the brand brings to the project. Lodha, for instance, has extracted the maximum value out of its partnership with Armani. We will have to see how the other partnerships work out,” he says.

Simply put, even the brand needs help to work. And there are those who have learnt that lesson better than others.

“Brand building in real estate is not easy,” Girish Shah, chief marketing officer of Godrej Properties, says with some emphasis. “We might get to extend the name of Godrej to real estate but there is a tremendous amount of hard work that goes into gaining the trust of the consumer. Along with the brand, quality needs to be extended too.” In 2010, the company had sales of Rs 313 crore which moved up to Rs 660 crore by 2014.

Godrej Properties’s success is linked to an asset-light business model adopted a few years ago. Functions such as conceptualising the development, design, marketing and sales are managed internally by Godrej Properties land is acquired through joint ventures with land owners and, significantly, the construction work is outsourced. This has helped the company keep the balance sheet light and expand rapidly across 12 cities in the country as of today. This model is particularly relevant given that, in real estate, setting up each project is akin to establishing a new factory with its own production cycle. Again, since the business is chunky and ‘goods’ get sold only during certain months of the year, there is a fair amount of uncertainty. Thus, growth on a quarter-to-quarter cycle, like, say, in an FMCG company, is difficult to achieve. But Pirojsha Godrej is confident that with proper processes and secular expansion, it is possible for the business to develop at a steady pace.

He knew he had a tough task on his hands when he took over the reins at Godrej Properties in 2012. (He was just 32 years old at the time.) But the son of industrialist Adi Godrej, Pirojsha also understood the power of the Godrej brand. “I decided to think like my customers,” he tells Forbes India. The idea was to create the story of the customer rather than that of the developer. “Customers today don’t want to feel like they’re being sold to,” says Pirojsha who has embraced both the old and new forms of communication with his customers. While the company continues to use traditional print advertising, it has also built a social media presence. Its website allows it to reach the international buyer who can view sample flats with a 360 degree view and talk to customer care on a 24x7 basis.

Now Godrej is a legacy brand. Most other real estate brands have not yet acquired a status that ensures takers at all costs. “Unfortunately, these brands, at least yet, are not so strong. For example, take a BMW car. Even if the monogram falls apart, you will spend a lot of money to get another one. But if the neon sign of the developer’s name is falling apart, I will, as a society member, never spend money to put up another one, no matter what the name of the real estate company is,” says Gulam M Zia, executive director, advisory, retail and hospitality, Knight Frank India.

These concerns are recent, partly because few developers were trying to differentiate themselves even around 2006. Any effort at the time was only directed towards a specific project.

The Lodha Group, however, decided to take a different route.

When Abhishek Lodha took over as managing director of the company from his father Mangal Prabhat Lodha, he was clear that he wanted to first make Lodha a corporate brand. “The brand carries certain values and these values are what buyers are buying into eventually,” he says. “Any product like real estate is complex because you are buying it for [at least]around four years. This, ultimately, requires a huge amount of credibility for the buyer to decide, ‘Yes, I do want to buy it’. And the brand is what brings the credibility.”

He is putting his money where his mouth is.

Lodha is currently developing an estimated 53 million sq ft of prime real estate with the largest land reserves in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), and has 28 ongoing projects across London, Mumbai, Pune and Hyderabad. It is also setting up World One, projected to be the world’s tallest residential building, in Lower Parel. The group also claims to have recorded the biggest land deal in India till date, buying a plot in Wadala for Rs 4,053 crore from the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) in 2010, where it is developing New Cuffe Parade. Besides this, the group is building Palava City, one of the biggest townships in India, in the Kalyan-Dombivli area near Mumbai.

While Lodha recognises that the brand caters more to premium buyers, he is aware of the opportunity from buyers looking for mid-range housing. With that in mind, he launched Casa, an endorsee brand, and took it to places like Dombivli and Kalyan quality and luxury were not compromised but the cost of maintenance and price of the product dropped significantly. These products command a premium of around 30 percent in the locality. “The product brand name becomes important to us because every product needs to solve a fundamental problem for the consumer and if it doesn’t, there is no need for the product to exist,” says R Karthik, chief marketing officer of Lodha Group. How it works: The team first zeroes in on the problem to be solved and then decides on the product and, finally, the brand name. “Market research doesn’t work in real estate because it isn’t easy to understand consumer behaviour based on dormant aspirations. Brands are created on consumption and not on purchase,” he says. This learning was re-emphasised in 2008 when the financial crisis saw investors who had bought flats running away from the projects, leaving the developers in a lurch. “We were selling to real buyers and not to investors,” he says.

Lodha, as a ground-up real estate brand, had its own learning curve. Meanwhile, other, already established brands in the corporate space, had a different kind of problem.

When Tata Housing launched operations in 2006, it took a while for the company to get the right to use the Tata Group’s logo. “We got it in 2007,” says Brotin Banerjee, MD and CEO of Tata Housing. “The Tata Group has set certain parameters that need to be met to retain the use of the logo. Otherwise the logo can be taken away from Tata Housing.” Tata Housing also has to consistently justify the use of the logo by ensuring strong brand equity. And the proof of the pudding has to be in the form of tangible numbers. Four years back, Tata Housing hired Nielsen India, a global information and measurement company, to annually survey its brand equity. “The idea is not to see whether we are strong or weak but to have a systematic approach to tracking our brand equity. We want to know our strengths or future strength that we would like our brand to convey,” says Banerjee.

The Anand Mahindra-led Mahindra Group has similar expectations from its real estate company, Mahindra Lifespaces. As one of their group CFOs mentioned in a board meeting, “The only royalty that we demand of the group companies is to protect the reputation of the brand and to live by the brand value.”

The Nielsen survey for Tata Housing takes the opinion of 2,000 home buyers (mostly non-Tata Housing buyers) across markets (NCR, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Kolkata) and across segments (low-cost, affordable, premium, luxury) in which the company has a presence. The first survey was done in 2011 in which Tata Housing scored a brand equity score of 0.6 (out of 10). Today, it has a score of 3.

This jump is not a coincidence, says Banerjee. “We have consciously worked towards improving our brand image,” he says. In an industry battered by falling sales and rising debt, brand equity has not been a priority for developers. But as Banerjee points out, buyers are driving the demand for a strong brand. “They are demanding that we become process-centric and transparent. It is accentuated by the fact that the market is tough and sales are not happening. It has sunk in among builders that they have to reform or perish.”

While companies with existing corporate brand equity—for instance, Mahindra—get recall from customers, they face another kind of problem: That of disassociation. In September 2014, Mahindra launched its costliest apartment till date, in a project called Luminare in NCR: This is a luxury housing project in Sector 59 of Gurgaon on Golf Course Extension Road, a prime area. There are 360 units in this project with prices ranging from Rs 4 crore to Rs 8 crore. The project will be completed by 2019. Forty units have been sold so far. “We have done excellent sales even in a difficult market,” says Anita Arjundas, managing director of Mahindra Lifespaces.

A bulk of the buyers in this project, around 35 percent, are NRIs who have shown keen interest because of their trust in the Mahindra brand name, she says. At the same time, she is aware that not many relate the Mahindra brand to real estate (since not many know that Mahindra operates in this space). The company plans to become more aggressive in its marketing and will work towards improving its brand recall in the real estate industry, she says.

It won’t be easy.

As key players like Banerjee assert, the nature of the industry makes it difficult to establish good brand equity. “We don’t have the product (home) when we sell it. Marketing in the real estate industry is all about selling a promise. Eighty percent of buyers look at a brochure and buy a house,” he says. “Consumers have far greater awareness when buying an FMCG product than while buying a house. This is why we often come across disappointed buyers.”

An often-ignored problem is talent, he adds. “Far more established industries attract more talent than a nascent industry such as real estate,” says Banerjee. “We have tried to attract talent from other industries which are process-driven, customer-centric and know the importance of walking the talk. They bring in the best practices from other industries.” For instance, Tata Housing audits all its completed projects to check if its customers are happy, a practice not often seen in the real estate industry.

For Tata Housing, delivery of projects has been a key differentiator. “We have delivered 4,500 units in the last seven years,” says Banerjee. When Tata Housing started in 2007, Banerjee says it didn’t have the advantage that the leading players had. “We were part of a new set of developers who didn’t have access to a historical land bank or existing good relations with the government authorities. So we focussed on delivery to prove we are good,” he says. (Banerjee claims that the company did not have access to Tata Group land.) “Our first project was an IT park in Whitefield (Bengaluru) which was a joint development with a land owner. I remember we didn’t have money, so I offered around Rs 9 crore as advance to the land owner to secure the land,” says Banerjee. But the fact is that delays and projects are in an unfortunate and inseparable relationship. Even the biggest brands are not exempt. This can either happen due to government processes or diversion of funds into other projects to build a land bank.

“Brand importance comes in when the product is under construction. While the product is under construction, I would be keen to give that 20 percent extra for the brand value because I know that they will not be late in terms of delivery,” says Knight Frank’s Zia. “To get timely delivery, I will pay that premium. But once it is ready, it doesn’t matter. Most of the brand differentiation then is on product quality. Not so much on which developer has done it.”

If brand creation was just about finding an attractive name and logo, and plastering it on the façade of developments, real estate companies would be laughing all the way to the bank.

As it stands, it isn’t. And those who are building credibility, quality and deliverability, are truly building a brand—one brick at a time.

(With inputs from Deepak Ajwani)

First Published: May 11, 2015, 07:30

Subscribe Now