Budget 2019: India Inc hopes for land, labour, agriculture reforms

A lowdown on what corporate India expects from finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman's maiden Union Budget

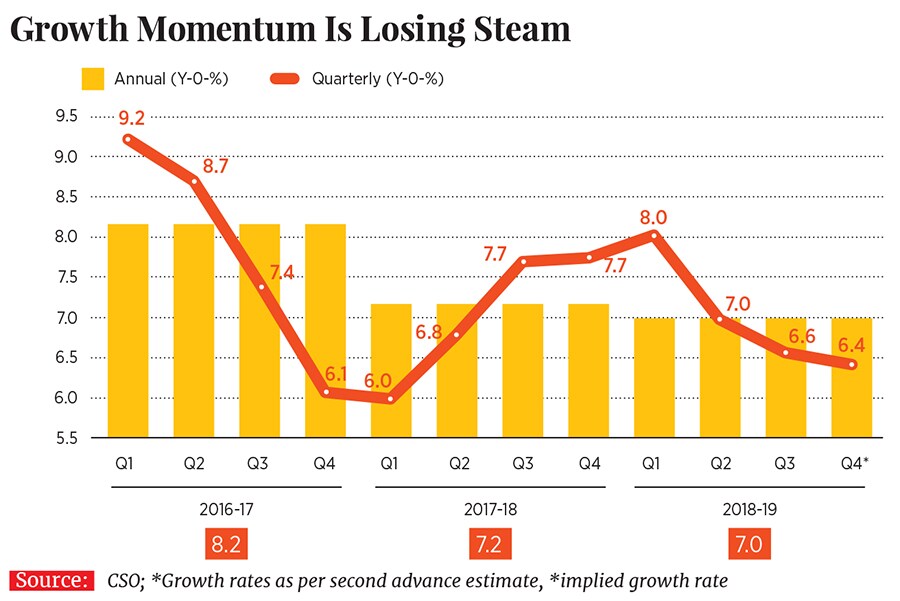

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur [br]Unemployment rate is at a 45-year high, GDP growth is at a five-year low. There is a revenue shortfall and a slowdown in consumption. Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman has a tough job on her hands as she gets ready to present her first Union Budget in July.

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur [br]Unemployment rate is at a 45-year high, GDP growth is at a five-year low. There is a revenue shortfall and a slowdown in consumption. Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman has a tough job on her hands as she gets ready to present her first Union Budget in July.

Even as the finance ministry took to social media early this month to invite suggestions, analysts and experts say it remains to be seen how the FM will balance between fiscal consolidation and boosting growth. While prudent fiscal management is preferred over the long term, they say focus on growth will be critical now.

Two immediate priorities are clear: First, to build momentum for investment, and two, address consumption slowdown, particularly rural. “The expectations from the market would be to cut taxes so that you leave more money in the hands of the consumers, have reasonably good allocations to the public capex plan, and then incentivise the private sector to start the whole capex plan. A balance has to be made between both,” says Rajat Rajgarhia, MD and CEO, institutional equities, Motilal Oswal Financial Services.

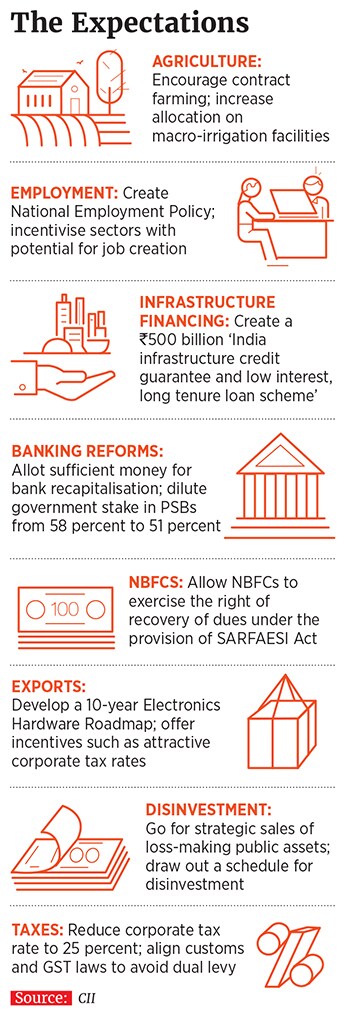

The Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), in a presentation to Revenue Secretary Ajay Bhushan Pandey earlier this month, suggested measures to strengthen consumption. This includes creating a National Employment Policy, as suggested by government think-tank NITI Aayog, and identifying and incentivising sectors in both manufacturing and services—like food processing, textiles, building, construction—which have a potential for job creation.Analysts and industry also point to the need for land and labour reforms to boost investment, manufacturing and employment. “If you were to diversify the economy from consumption towards investment, you need to boost manufacturing. And the three factors of production are land, labour and capital,” says Pramod Gubbi, founder, Marcellus Investment Managers. “Capital can be fixed through PSU banking reforms, a little improvement in the NPA regulatory framework, and, of course, from a long-term perspective, deepening the bond market in the country.”

For starters, the government must amend the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, which was tabled in 2015 but has still not seen the light of the day. The Act regulates land acquisition and lays down the procedure for granting labour compensation, rehabilitation and resettlement of people in India.

Analysts say that implementation of this regulation will enable the private sector to acquire land easily. Gubbi explains: “Along with the PSU reforms, the land consolidation plan should be implemented very quickly. Those two can solve some problems for land acquisition for the industry.”

Nirmal Jain, founder and chairman of IIFL Group, calls for a Real Estate Regulatory Authority (RERA)-style implementation of land acquisition policies. “Land acquisition remains a key challenge in setting up manufacturing capacity. The Land Acquisition Act, 2013, makes it a lengthy process and the government should aim to amend the Act to simplify it,” he says. “Since land is a state subject, the central government can provide a model law for land acquisition and then work with state governments to implement these changes—similar to RERA implementation.”

Labour laws, too, need to be eased, though Jain does not see this happening any time soon. “While industry has been demanding amendments in labour laws to provide flexibility to fire employees, the government is unlikely to implement this in the near term,” he says.

Bridging the skill gap goes hand-in-hand with labour reforms, and providing skilled labour remains a priority. “I do not think any of this is new. We have seen snippets of this under the previous NDA regime as well,” says Gubbi, hoping that labour reforms will be accelerated given that the NDA has won the recent general elections with a much stronger mandate.

Reforms are also needed in the agriculture sector to strengthen consumption. The CII has asked for increased public expenditure in agri-infrastructure like irrigation, seeds, cold storage and other inputs that increase farm productivity as well as usher in the “next agri-revolution by incentivising investments in technology—such as micro-irrigation, advanced seeds and digital platforms etc”.

Jain says the government should deregulate urea prices “to eliminate the imbalanced fertiliser usage in India”. The share of nitrogen fertiliser in India is approximately 70 percent, compared with the optimal level of approximately 60 percent, he points out, explaining that the central government has allocated ₹75,000 crore (0.4 percent of the GDP) for fertiliser subsidy in the interim Budget. Deregulation will reduce both urea usage and fiscal burden of subsidies. “The government should also make efforts to link the soil health card with fertiliser subsidies,” Jain explains.

Agriculture experts have argued in favour of free market pricing for various agri commodities. “Hence you need to have a functioning agri market system and that, as we all know, is politically sensitive,” says Gubbi.

If the government streamlines the process where the farmer directly receives competitive monetary compensation for crops, this will improve farming practices and yield, which will, in turn, lower prices, leading to a virtuous cycle. “But again, there has been no dearth of recommendations from experts so we don’t need to reinvent the wheel for solutions. It’s just a matter of political will to push through some hard decisions, especially when you have the mandate to do so,” Gubbi says.[br]In terms of fuelling investment, allocations to sectors that demand public capex will be something to look out for in the Budget. “Because the amount of money that they spend creates a second derivative, third derivative demand, be it roads or power,” says Rajgarhia.

Within infrastructure, roads have seen much development (projects more than doubled to about 7,400 km in FY18 compared with approximately 3,000 km in FY15, according to Jain), with the government delivering results for the pension fund community and several foreign funds overseas. This sector will, therefore, continue to do well, but other areas need to be figured out. Thermal power, for example, is reeling under significant challenges, say analysts.

Expenditure is also a challenge in infrastructure-creation. “The demands for raising government spending for reviving growth and limited fiscal space could constrain government spending on infrastructure in the near term,” says Jain.

While roads could still manage to get financing, other areas will be a challenge. “The pace of road construction has picked up in the last five years so there’s plenty of legacy projects that can be sold to the private sector, which can be a source of financing for new roads. Unfortunately, in other areas of infrastructure, we don’t have that,” says Gubbi.

In addition to a one-time bonanza that could come from the RBI as part of a reserve transfer, the other source of revenue could be if the government pursues disinvestment in its true spirit: By selling its stake to the private market instead of focussing on buybacks and mergers to meet its disinvestment targets.

India Inc has been hoping for a cut in corporate tax, and extra profits could, hopefully, be ploughed back into investment by companies. “In the light of tax rates cut by the US a few years ago and its looming impact on FDI in India, there is a genuine expectation from the industry that the new finance minister will slash the corporate tax from 30 percent to 25 percent irrespective of the size and turnover of the company with immediate effect,” says Amit Singhania, partner at Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co. He adds that there should also be a roadmap to further slash corporate tax to 20 percent over a period of two to three years.

According to Jain, the tax reduction may not lead to revenue loss as the Budget suggested that the effective corporate tax rate—based on a sample of 600k companies—was 26.9 percent even as statutory tax rate was 34.4 percent. “The elimination of tax incentives along with lower tax rates will simplify direct tax compliance significantly for corporates and also reduce tax litigations,” he says.

A revamp of the Dividend Distribution Tax (DDT) is another expectation. “Currently, the DDT rate is approximately 20.5 percent, which is quite high given the fact that the credit of DDT is not available in most jurisdictions,” says Singhania. “Further, if we evaluate the DDT from the perspective of repatriation of profits to foreign shareholders, then approximately 45 percent—35 percent corporate tax and 20 percent DDT—of pre-tax profits gets applied towards taxes. These kind of tax rates significantly reduce the internal rate of return for foreign shareholders.” One way to attract more FDI, he explains, is to rationalise tax rates. “The challenge to the new minister would be to manage the fiscal deficit. The possible solution is to increase the tax base by including those who are not contributing to the economy.”

The Budget is an annual accounting exercise and big-ticket reforms can be announced and implemented outside of it, too. But India Inc looks at it as a message sent out by the government on where it stands.

Rajgarhia of Motilal Oswal says, “The budget can send out a message that the government somewhere wants to incentivise a lot of the private sector capex. For example, if they raise the allocations to their housing scheme, if they allot more money to NHAI that also has to award a large number of road contracts, these will be critical to convey that the government is serious about boosting a programme capex in many of the sectors.”

First Published: Jun 24, 2019, 07:31

Subscribe Now