What UP's women want

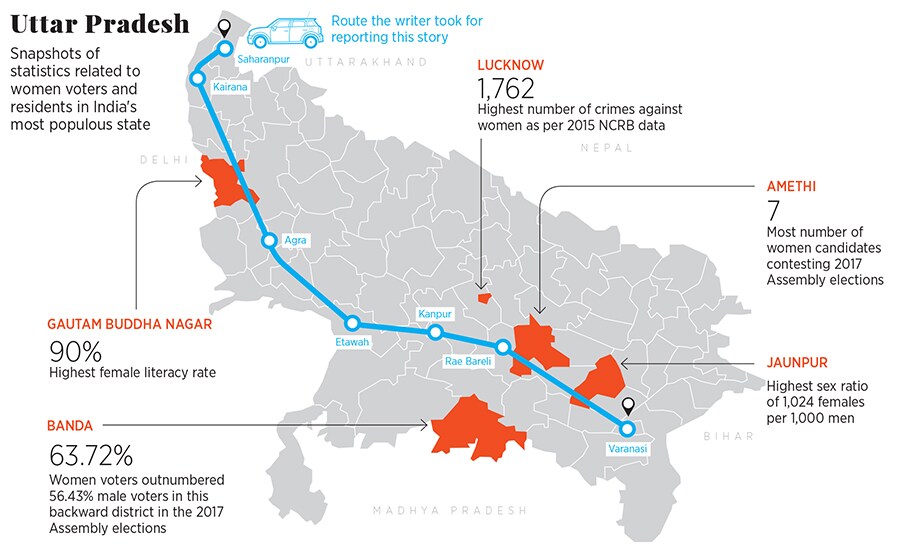

From Saharanpur in the west to Varanasi in the east, Forbes India travels across India's most populous state to explore how women—going beyond entrenched caste dynamics—want to vote for everyday freed

Congress Party supporters gather to watch Priyanka Gandhi Vadra during her campaign rally on March 29 in Uttar Pradesh

Congress Party supporters gather to watch Priyanka Gandhi Vadra during her campaign rally on March 29 in Uttar Pradesh

Image: Atul Loke / Getty Images

A framed photograph of Dr BR Ambedkar is among the few possessions in Neelam’s unplastered and unpainted brick home. The streets of her neighbourhood in Uttar Pradesh’s (UP"s) Chilkana Sultanpur town are in darkness, with lit bulbs inside nearby homes being the only sources of light. “Abhi toh sab umeed pe kayam hai [now everything is riding on hope],” says the 51-year-old, indicating that she has high hopes for the candidate she will vote for on April 11. While Neelam, who studied till Class 12, is proud to be among the few “saksham” (able) Dalit families that “believe in getting their girls educated”, in her neighbourhood comprising 100-odd Muslim and Dalit homes, it is still rare for women to pursue graduate studies or seek employment thereafter.

“When I was married into this village three decades ago, people just lived in jhopdas [shanties] and women rarely stepped out of their homes,” says the mother of three, who admits that nothing much has changed when it comes to women being ‘allowed’ to work, except that some of them work on farms, help in anganwadis, or participate in local self-help groups (SHGs).

According to her, the one autonomy women are beginning to claim for themselves is the right to vote as per their choice. “I feel women have to decide for themselves, no matter what. The government has not even done 10 percent of what they promised. We do not feel safe walking on the roads, Dalits and Muslims live in fear... they don’t know which word or action will incite violence against them,” says Neelam, who works with her husband to grow wheat, rice and sugarcane.

Her neighbour Sahana Parvin interjects that she only prays for the “mahaul” (environment) to remain peaceful. She believes that the 2013 riots [between the Hindu Jat and Muslim communities that left 62 people dead and nearly 50,000 displaced] in the neighbouring Muzaffarnagar district has left a lingering unease among the two communities. “Hamari basti mein toh Hindu-Musalman milkar rehte hain [Hindus and Muslims co-exist peacefully in our neighbourhood], but we can only hope that the situation remains safe,” says the 47-year-old. “Who knows how politicians act when they are in the seat of power.”

Chilkana Sultanpur is part of the politically significant Saharanpur constituency, from where the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) flagged off its election campaign in the state, and the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP)-Samajwadi Party (SP)-Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD) combine held its first joint rally on April 7.

In 2014, Saharanpur—where 69 percent of the 34 lakh population live in rural areas—registered a 74.24 percent voter turnout, among the highest in the state. And if the women, who comprise 47 percent of Saharanpur’s total population, are to be believed, they will exercise their franchise this time too. As Neelam puts it: “We need equal education for all, we need safety...the youth need rozgaar [employment]. And this cannot happen if we waste our vote or don’t vote right.” Making it count

Making it count

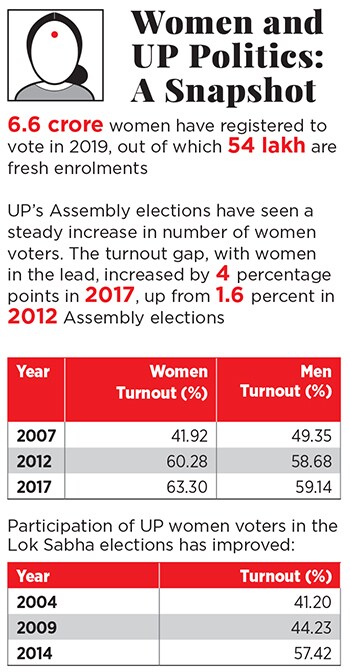

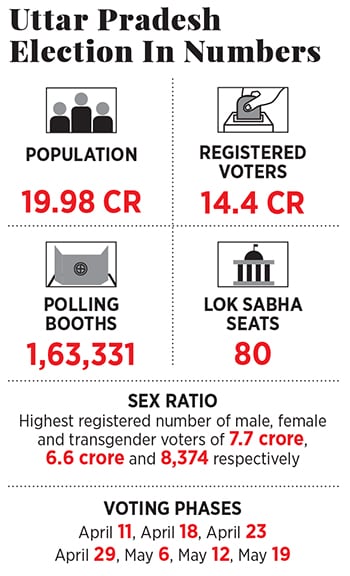

Everyone’s eyes are on the poor and populous Uttar Pradesh, which, with 80 Lok Sabha seats, holds the key to winning the elections. The state that elected India’s first woman chief minister Sucheta Kriplani in 1963 has had a steady trend of women outvoting men. The 2017 Assembly elections, for instance, saw 63.26 percent women cast their votes, as opposed to 59.43 percent men. Women widened their turnout lead by 4 percentage points, up from 1.6 percent in 2012 Assembly elections.

The 2014 General elections also saw some closing of the gender gap, with 59.13 percent men and 57.42 percent women arriving at the polling booths. In 2019, about 6.6 crore women are included in the electoral rolls in UP, out of which 54 lakh have registered this year.

That said, psephologists are also pointing to a supposed 4.5 percent shortfall of women voters in the electoral roll [Census 2011 data suggests that by 2019, women will be 97.2 percent of the men’s population, while the Election Commission data states that women are only 92.7 percent of male voters]. This means that between UP, Maharashtra and Rajasthan alone, about 21 million eligible women might not vote. In UP, this roughly translates to about 85,000 women per constituency. This challenge notwithstanding, women as a voter bloc stand to play a significant role in the upcoming elections.

Ahead of the seven-phase Lok Sabha polls starting on April 11, Forbes India travelled over 850 km to cover seven key constituencies across UP, which were chosen on the basis of electoral significance, women voter turnout history, and them being representative of a cross-section of female voter population, across age, class and caste backgrounds. The idea was to explore women’s voting behaviour through gender and socio-economic hierarchies, and understand the expectations and motivations behind them exercising their franchise.

Gilles Verniers, co-director of Ashoka University’s Trivedi Centre for Political Data, says that for parties, women have become as important a category as other caste minorities, and that women are voting more independently than, say, two decades ago. “Women tend to outvote men based on two broad characteristics: One, for parties with a credible record of development, and two, for parties that do not have the reputation of favouring any particular public group.”

Going one step further, women like Kanpur resident Preeti Singh Chauhan are completely sidelining political parties. “I have nothing to do with any party. I will vote for a candidate who will work to solve problems in my locality,” says the housewife, who believes that though the BJP made women’s safety an electoral issue, the Yogi Adityanath-led state government does not seem to have prioritised gender-based violence. “I feel that Akhilesh Yadav’s UP 100 [where over 3,200 vehicles of the UP police attended emergency/ distress calls from women across the state within 20 minutes] was a more visibly impactful initiative for women’s safety.”

Numbers, however, suggest that only a few urban women have the ‘candidate over party’ mindset. A survey conducted for Forbes India on the Neta app among 11,222 voters indicated that 81.20 percent would vote for a political party, while only 18.80 percent women would decide based on a candidate’s merits. That said, another survey on the app polled among 9,198 women had 58.22 percent saying that they would vote for a party or candidate that promises more economic opportunities, followed by safety (21.41 percent) and better education (20.37 percent). (Clockwise from top) Sahana Parvin from Saharanpur wants to vote for communal peace for Neetu Maurya, who owns powerlooms in Varanasi, voting seems like an aside after demonetisation and GST hit her livelihood Seema, Chidana and Shanti Paswan in Raebareli say rising expenses are not matched by income Babli, Neelam, Mainwati and Sushma in Chilkana Sultanpur say women must vote for causes that matter to them

(Clockwise from top) Sahana Parvin from Saharanpur wants to vote for communal peace for Neetu Maurya, who owns powerlooms in Varanasi, voting seems like an aside after demonetisation and GST hit her livelihood Seema, Chidana and Shanti Paswan in Raebareli say rising expenses are not matched by income Babli, Neelam, Mainwati and Sushma in Chilkana Sultanpur say women must vote for causes that matter to them

Images: Sahana, Babita: Amit Verma Neetu, Seema: Divya J Shekhar

Activist Rehana Adeeb, who rehabilitated female victims of violence during the Muzaffarnagar riots, says that the triple talaq debate started by the BJP is largely being looked at as a political decision by most women, who are upset about various other direct threats being unaddressed. “What about making public spaces safe for women? What about the lynchings in the name of cow protection? Who will address shutting down slaughterhouses and meat shops that mostly employ Muslims, casting a question mark on people’s livelihood?” says Adeeb. On the heels of the elections, her mission is to convince rural women to vote for reasons that matter to them.

Awareness initiatives by activists like Adeeb and local SHGs are important because in places like Kairana, in western UP, voting decisions are either mostly taken by men on behalf of women, or along communal lines. The Muslim dominated-constituency—Ground Zero of a supposed exodus of hundreds of Hindu families in 2016 because of sectarian violence after the Muzaffarnagar riots—had emerged as a BJP stronghold in 2014 after their candidate Hukum Singh defeated Tabassum Hasan of the RLD. In the by-poll last October, however, the BJP lost to Hassan, who is now contesting the general elections on an SP ticket.

Living in the outskirts of Kairana, 47-year-old Kavita knows none of these dynamics. She narrates how her family of four (husband and two sons) was uprooted from Kairana’s Kayastha wada in 2016 because all their neighbours were leaving.

“Mostly Muslim families live in the area now. When we tried to sell our property there, we got only ₹20 lakh, which is half its value, because of demonetisation,” she says, refuting Adityanath’s claim that under his rule, Hindu families who had left Kairana have returned. “Nothing has changed. We have lost our money, our property. Politicians come every year, asking for votes. But they are concerned only about their kursi [chair], not people.” Despite this, when asked whether her experiences will impact her voting decision, Kavita merely shrugs. “My husband says Modiji is doing good for the country, so I’ll probably just vote for him.”

About 250 km away in Agra, 40-year-old Babita Koranga openly supports the BJP too, but for different reasons. She belongs to the Fatehabad constituency, which has consistently been the frontrunner in terms of women voter turnout. The last assembly elections saw 48.34 percent women turn up in the polling booths, which was highest among all the nine assembly seats in Agra.

“Voting is a matter of perspective. People who want to find faults with a party they don’t like will find faults no matter what,” she says. “Personally, I feel that in the last five years, Agra has become much cleaner than it used to be. Garbage management has improved, especially in the Sadar Bazar area [where she runs a salon]. The credit should go to the ruling party for promoting cleanliness, even at the national level.” Of women&neFor women?

Of women&neFor women?

Increasing women voter turnout has not led to a simultaneous rise in the inclusion of women by political parties. Representation of women in parliament is stagnant, at 11 percent. The 2019 Candidate and Legislators Data from the Trivedi Centre for Political Data indicates that in UP parties have not done much to give more tickets to women this time around as well.

Of the 61 candidates declared in the state as on March 2, the BJP has given just nine tickets to women, which includes no Dalit or Muslim representatives. There are two Brahmins, two Jats, two Khatris, one Nishad, one Maurya and one Kayastha candidate. The Congress list is a bit more diverse. Tickets have been awarded to 10 women, including four from the scheduled castes (SC), two Brahmins, one Muslim, one Bania, one Rajput and one Christian. The SP-BSP-RLD alliance has given the least number of tickets to women. At the time of going to press, they had given tickets to six women candidates, including one Vaishya, one SC, 1 Gujjar, one Yadav and one Kurmi.

Verniers interprets this as a reflection of the BJP’s elitist bias, and the willingness of parties in the alliance to stick to the rules of the political game, which have traditionally been pro-men.

Unfortunately, certain key constituencies having women in power do not seem to be setting much of a precedent. While BJP’s Hema Malini has received flak for neglecting Mathura, the Gandhi family bastion Raebareli [represented by Sonia Gandhi] tells a similar story. In Garhi Mutwalli, 28-year-old Shanti says that she has not received a ration card for the last three years, and that local representatives are unapproachable.

Belonging to the SC Paswan community that is towards the bottom of the village’s social hierarchy, her small brick home does not have electricity. Shanti thinks perhaps this is a blessing in disguise. “We got a power connection as part of the rural electrification programme, but no matter how little energy we consume and, despite frequent power cuts like this, the bill is always high,” she says.

Then there are expenses associated with the free LPG gas connection under the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana, which requires the family to spend around ₹750 for refills, which is again expensive. “The only reason we are sticking with the gas connection is because the traditional chulha [stove] is harmful for health in the long run,” says Seema Paswan, Shanti’s sister-in-law.

“To top it all, the building of the only government school in the vicinity is crumbling and teachers never show up, so we have to send our two kids to private schools. In short, the expenses keep increasing, but where is more aamdani [income] to support that,” wonders Seema. The family’s source of income is agricultural labour.

Survey data from the Neta app shows that after Priyanka Gandhi Vadra’s entry into politics, many voters in eastern UP have swung towards Congress. “Out of the 41 constituencies there, Congress was in third place in about 18 of them. After Vadra’s entry, Congress rose to second place. Either BJP or BSP is in first place,” says Pratham Mittal, founder, Neta app. “The voter bloc leading this shift is women. Priyanka Gandhi Vadra is appealing to women, maybe because before her, apart from Mayawati, women did not have too many political role models to look up to.”

Meanwhile in eastern UP, another woman-led party Apna Dal, has settled for just two Lok Sabha seats in an alliance with the BJP. Party chief Anupriya Patel, who remained unavailable to comment for this story, will contest from Mirzapur.

Rekha Singh, who works for women empowerment through her nonprofit Vishwas Sansthan in Raebareli, is disappointed that despite the Member of Parliament (Sonia Gandhi), Member of Legislative Assembly (Aditi Singh) and District Magistrate (Neha Sharma) being women, leaders are often not connected to people at the grassroot. “Instead of depositing money in people’s bank accounts [referring to the Congress’s Nyuntam Aay Yojana (NYAY)], why don’t people in power concentrate on creating jobs that will assure families a permanent income and make them truly independent? We hope Priyanka Gandhi’s involvement will change things,” says Singh.Grassroot realities are not too rosy in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s constituency Varanasi either. Following their family trade, weavers who occupy a significant percentage of the electorate largely live in poverty. Satyaprakash Maurya, 68, says that he and his wife Susheela, 58, are among the last of the 30,000-odd bunkars (weavers) in Varanasi. Even his sons have taken to powerlooms, which has over 1.5 lakh workers currently, and is riding on commercial demand.

“On the one hand, the PM promotes handlooms and Banarasi sarees, and on the other, craftsmen like me who spend about a month weaving the fabric are asked to pay a bribe to receive their pension. I refused to pay it and haven’t received a penny in the last six years,” he says, while Susheela adds that addressing systemic corruption that prevents implementation of welfare schemes must be checked.

People operating powerlooms haven’t had it easy either. Neetu Maurya from the Gaura village in Varanasi earlier had 20 looms providing sarees to the market. With demonetisation, much of her stock remained unsold due to cash scarcity. Then with the Goods and Services Tax, she was forced to scale down operations and lay off about 10 craftsmen. Powerloom workers are given between ₹150 and ₹200 per day. “We are left with 10 looms now, and are taking each day as it comes. Voting seems like an aside when my priority is to ensure stable livelihood for my family, which politicians across parties do not seem to be concerned about.”

Improving equal access

Experts agree that an important reason for the rising turnout among women, especially among first-time voters, has been the aggressive enrolment drives conducted by the Election Commission (EC). Verniers from Trivedi Centre for Political Data suggests women’s access to polling booths and their participation in the public sphere is directly linked to other social problems. Falling contribution of women in the workforce, for instance, results in greater indoor confinement, and ultimately strengthens patriarchal mindsets.

Such mindsets perhaps explain the cynicism of a group of first-time voters in Etawah in central UP. The young paramedical students of the state-run Uttar Pradesh University of Medical Sciences, located in SP stronghold Saifai [the birthplace of party supremo Mulayam Singh Yadav], have little hope of their vote making any difference to their problems. Today, even if they face harassment within or outside campus, they are told to “deal with it” themselves and take responsibility for their own safety. Their institution does not have a grievance cell.

“The college doesn’t provide a basic skeleton or equipment for practical training. Classes are conducted and dismissed on the teacher’s whim. They shut us up saying that girls must be grateful for just being sent to college and if we want more facilities, we must pay for it ourselves,” says one of the students, not wanting to be identified.

“If our parents had that kind of money, why would we be studying in a government college?” Because of this, the girls say they will vote because they have to, not because they believe it will change anything for them or other women.

Verniers believes absolute equality is important. “There is an unintended misogyny in the idea that women will clean up the political mess men have created, meaning that when parties talk about women inclusion, it should be encouraged in the name of equality. Not through any instrumental notion that bringing more women in politics will help achieve a particular positive outcome,” he says, explaining that women should share equal responsibility in upholding probity and ethics of the democratic system.

First Published: Apr 08, 2019, 12:28

Subscribe Now