Shakti: Gunning for more women in politics

A non-partisan collective is targeting the general elections for equal representation of women in Parliament, but the road to gender-just politics is tricky to traverse

IT professional Tara Krishnaswamy (fourth from left, standing), co-founded Shakti last year. The non-partisan citizen collective 600-odd volunteers across India

IT professional Tara Krishnaswamy (fourth from left, standing), co-founded Shakti last year. The non-partisan citizen collective 600-odd volunteers across India

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Vinod Rathod of the Delhi Police has been manning the Parliament gates for four years now. Like his namesake singer, he can also skilfully hum a tune or two, he tells this journalist, who is there to meet members of Shakti, a non-partisan citizen's collective campaigning for equal representation of women in legislation. The pan-India collective is in Delhi for a national meet.

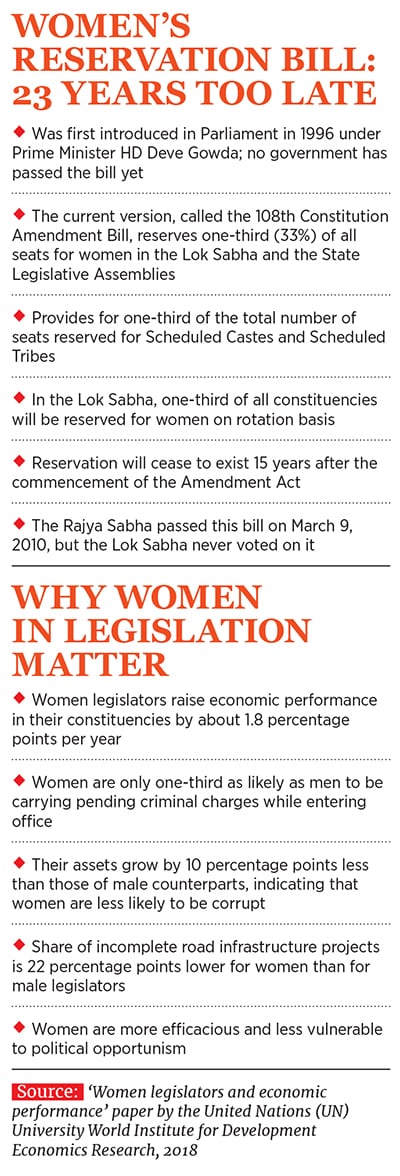

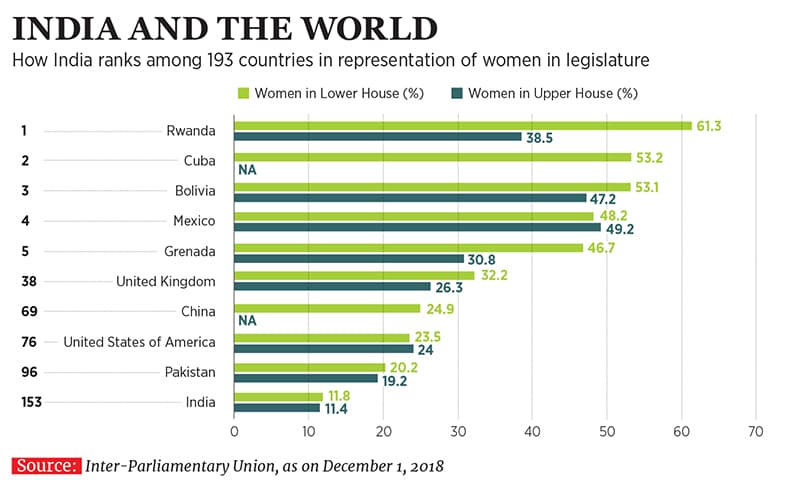

Viewpoints similar to Rathod’s, of championing gender equality in politics, have been aired in the public sphere for many years now. Numbers, however, point to a contrasting reality. The percentage of women elected to Parliament has stagnated between 3 and 11 percent ever since the first Lok Sabha was constituted 67 years ago in 1952.

Even today, women constitute only 11.8 percent (64 of 543) seats in the Lok Sabha and 11 percent (27 out of 245) seats in the Rajya Sabha. A 2017 report by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) and UN Women indicates that between 2010 and 2017, the share of women representatives in the Lok Sabha rose only by one percent.

This is a paradox, considering the increasing share of women voters in the electorate. From 48 percent in 1971, the turnout of women increased to 60 percent in 1984 and then to 65.3 percent during the 2014 general elections (as against 67.1 percent turnout for men). The gender gap among voters has shrunk to 1.8 percent.

The recently-concluded assembly elections in Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Mizoram echo the trend. The number of women voters surpassed the number of men in 24 of the 90 constituencies in Chhattisgarh. In Madhya Pradesh, this was seen in 51 of the 230 constituencies. In Mizoram, there are 19,399 more registered women voters than men.

“Political parties do not see representation of women as priority. They are not accountable to citizens and function like they are outside of the system,” says Tara Krishnaswamy of Shakti. An IT professional from Bengaluru who has worked in the citizen activism space for over a decade now, Krishnaswamy co-founded Shakti in December last year as a non-partisan group of like-minded people who will work towards better representation of women in the Parliament and state assemblies, starting with the general elections this year. “We are not a non-profit, but a citizen's movement that has committed itself to the cause, regardless of caste, ideologies, region or religion.”

Stronger Together

Shakti’s core group of members and volunteers comes from various backgrounds. While co-founder Rajeshree Nagarsekar is a writer and political activist, other members include leaders like Nisha Agrawal, who became the first CEO of Oxfam India after a career at the World Bank spanning several decades Jyoti Raj, co-founder, Campaign for Electoral Reforms in India (CERI) Swarna Rajagopalan, political analyst and social entrepreneur Flavia Agnes, women’s rights lawyer Dhanya Rajendran, co-founder, The News Minute Nisha Susan, co-founder of feminist online magazine The Ladies Finger and academician Padmaja Shaw.

According to Krishnaswamy, their 600-odd volunteer base comprises people across India who are usually active in their respective cities. The core group is of nearly 115 members, and 40 of them are active in all events/campaigns conducted by Shakti across the country. Resources and funds are crowdsourced. At the national meet in Delhi, women politicians, academicians, political analysts and journalists talked about ways to increase representation of women, empower existing women legislators and sensitise voters ahead of the elections in April-May.

“Politicians do not take women seriously because we do not take ourselves seriously. We do not vote as a women’s bloc or demand more female representation from political parties. We vote along caste or religious lines,” says Nisha Agrawal.

She points to the legislation mandating 50 percent representation of women at local government levels, which has led to about 13.72 lakh elected women representatives in India’s Panchayati Raj Institutions. There are numerous studies that show how these women legislators have raised the economic performance and social security of their people at the grass-roots level, she explains.

“Legislation sets the ball rolling. That, however, should not stop political parties from giving tickets to women of their own volition,” Agrawal says. “Every party has included the Women’s Reservation Bill [which reserves 33 percent Lok Sabha seats for women] in their manifesto but nobody wants to table or pass it. So for now, the least parties can do is ensure they give more tickets to women than they did last year.”Political analyst Preethi Nagaraj agrees parties should do more. “When 50 percent seats at the panchayat level are reserved for women, what happens to them after that? Where do they disappear? Aren’t they competent enough to fight the next level of elections?” she asks, likening this situation to that of engineering students or women in technology, which is characterised by high enrollments and representation in colleges, but low workforce participation.

The current political structure is built to include women in small, non-offending roles that do not affect the larger party structure and functioning, says Nagaraj, who is not associated with Shakti. The chain of representation is not allowed to continue and women have no natural career progression to bigger political roles. “Parties keep fielding fresh candidates who are considered more ‘winnable’, thus continuously changing the structure of competition for women. We continue to lose experienced women leaders who are already aware of operational responsibilities and could be an asset to the party,” she says. “We have a skewed mindset that believes that women are not intellectually or economically strong to carry out a successful campaign or win an election.”

Kanimozhi, Rajya Sabha MP from Tamil Nadu representing the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), believes women have to be twice as hard-working and intelligent to succeed. “Politics, power and party structures are not made to accommodate women. Party workers have told my father (late Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M Karunanidhi) not to give tickets to women candidates as it is perceived that they won’t campaign or win effectively,” she says. She was speaking in Delhi at the meet organised by Shakti.

Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) spokesperson Shaina NC agrees that representation has not gone beyond tokenism, even if India has women taking up important Cabinet portfolios like defence and external affairs. “Men like to keep their power dynamics alive, so women need to support women. If you are in a position of power, empower other women without thinking of them as a threat,” she says.

Even today, certain stereotypes and prejudices influence decisions on the roles or portfolios women can handle, and there are many who do not take women seriously, believes Congress IT cell chief Divya Spandana. “The [Reservation] Bill really needs to pass, and for that, all of us have to come together across party lines, raise our voices and ensure that it is done.”

Krishnaswamy says that Shakti seeks to maximise the impact that has been created by isolated, independent efforts of women’s groups over the years. It is “foolish”, she says, to imagine that everything needs to be built brick by brick from scratch, naming organisations and individuals like Women Power Connect, Aleyamma Vijayan (secretary, Sakhi Women’s Resource Centre) and Ekal Nari Shakti Sangathan that are already working towards political rights for women in different capacities.Shakti’s recent ‘Call Your MP’ campaign, for instance, was also executed with the help of such diverse organisations, where participants called their respective MPs and demanded that they support the Women’s Reservation Bill, which was approved in the Rajya Sabha in 2010, but lapsed in the 15th Lok Sabha. Over 500 people across the country called 543 MPs. Only 373 numbers connected, out of which 130 answered and 127 said they would support the bill.

“There is strength in numbers. The more we aggregate such efforts, the more powerful we will be,” Krishnaswamy says, explaining that Shakti will also focus on finding allies in men every step of the way.

Elections and Beyond

Human rights activists believe that economic policies adversely affect women more than men, and only representation will ensure empowerment.

Other experts call this is a multi-layered problem with links to issues like inaccessible education or the increasing school dropout rate of young girls. “This is a vicious circle. Apart from lack of basic education, the role of women is often diminished in households and society. They face multiple barriers and intense scrutiny,” says Akriti Gaur, senior resident fellow, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. The Shakti volunteer says that no critical mass representing women in Parliament results in lower public participation and exclusionary policies.

Sushmita Dev, Congress MP from Silchar, Assam, agrees. “Patriarchy begins at home. Fewer women politicians is the result of fewer girls in schools and colleges. Emancipation of women starts with educational and economic empowerment,” she says.

Krishnaswamy realises that this movement cannot be restricted to one election. Shakti, she says, is a work in progress that will continue even if parties do not give more tickets to women this time around. Detractors have often asked her how voting for women is different from voting for, say, a certain caste or religion. “Democracy is first about representation, then about merit. Somebody who is meritorious but not representative of me, cannot fully understand or solve my problems,” she says, comparing it with a situation of expecting rich, white males to understand and represent African-American women. “So let us first ensure women are represented, and then find the most meritorious among them.”

Post-elections, following in the footsteps of women’s caucuses in the US, Krishnaswamy wants to hand-hold women politicians and aspirants. “Campaigning is not an inclusive or systematic practice in India. There is need for training, best-practices sharing and capacity building around electioneering. We want to enable more women to network, raise funds and gather volunteers around their campaigns,” she says. “I firmly believe that every little push matters. A lot can change if we women stand together, across cultural differences and party lines.”

First Published: Mar 08, 2019, 15:15

Subscribe Now