Vicky Kaushal might be hot, but he did a propaganda film and I don’t like him anymore,” was a tweet by Delhi-based media consultant Tanzila Anis that snowballed into a Twitter-storm. While trolls hurled personal insults, others discussed whether a war film could be politically-motivated, if the movie industry has the moral responsibility to stay away from politics, and the difference between ‘propaganda’ and ‘patriotism’.

Meanwhile, filmmaker Anurag Kashyap rushed to defend his contemporary Aditya Dhar’s film chronicling India’s supposed surgical strikes on Pakistan in 2016. “The jingoism spouted in Uri was far lesser than the jingoism I see in American movies or war movies from anywhere across the world. I think we watch everything from the coloured glasses of the time we live in and just don’t trust anyone’s intention,” he said in an unrelated series of tweets.

Long story short, these are just a few examples of how, ahead of the general elections in April-May, people are seriously debating whether the sudden slew of political films and biopics are timed to win parties a few brownie points. Be it informed or speculative, serious or shallow, everyone seems to be talking, forming opinions, taking sides. There is constant chatter, especially on social media. ![g_112555_political_films_280x210.jpg g_112555_political_films_280x210.jpg]() Past Imperfect, Present Tense

Past Imperfect, Present Tense

Given how entrenched daily life in India is into the politics of the land, the history of critically-acclaimed political biopics is not a particularly rich one. There have been intermittent releases like Gulzar’s Aandhi (1975), supposedly based on former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi Mani Ratnam’s Iruvar (1997), which was inspired by actor and Tamil Nadu Chief Minister MG Ramachandran (MGR) and Gnana Rajasekaran’s Tamil film Periyar (2007) on politician-social activist Periyar EV Ramasamy, the father of Dravidian nationalism.

There have also been well-received political films, again scattered, including Amrit Nahata’s Kissa Kursi Ka (1978) that was banned during the Emergency because it was believed to be a satire on the Indira Gandhi administration Rahul Dholakia’s Parzania (2007) based on the 2002 Gujarat riots that theatre-owners refused to screen fearing backlash Sudhir Mishra’s Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi (2005), which was set during the Emergency and Anurag Kashyap’s Gulaal (2009) about student politics in present-day Rajasthan.

This is why, perhaps, more than ten political biopics suddenly being released or announced in the 2019 pre-poll season seems like an unconventional trend. “I have never observed so many political films timed ahead of the elections before,” says National Award-winning film critic Baradwaj Rangan.

These films, made across languages, have found protagonists in politicians like late Shiv Sena supremo Bal Thackeray, and late Andhra Pradesh Chief Ministers NT Rama Rao and YS Rajasekhara Reddy. Two biopics on PM Narendra Modi are also in the pipeline, along with one on late Tamil Nadu Chief Minister J Jayalalithaa.

“Given that cinema is a widely-consumed, accessible medium, there should be some curbs on politically-motivated films releasing so close to the elections. The Election Commission might want to take a look at this [content of such films],” Rangan says, cautioning that there is no clarity on whether these films attract the number of crowds required to translate into victory votes. Because at the end of the day, he reasons, the mainstream movie-going audience is “just looking for entertainment”.

According to political analyst Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, who is certain that films are gradually being used as a “means of political canvassing”, the underlying idea might be for parties to increase their appeal among the public. “Movies definitely help you make headlines and, these days, there is an understanding [in the political circles] that if you are being talked about, you are actually scoring brownie points over the rival,” says Mukhopadhyay, who has also written the biography on PM Modi titled Narendra Modi: The Man, The Times.

What is unfortunate about the trend, he observes, is that most people setting out to make political biopics are interested only in creating hagiographies or hit jobs, which would eventually lead to poor-quality, forgettable films. “A producer, for instance, made preliminary enquiries about whether my book could be the the basis for a biopic on Modi. Nothing came out of it because they understood that I was not into the propaganda mould, or interested in a hagiography.”![g_112557_reel_politics_280x210.jpg g_112557_reel_politics_280x210.jpg]() The Politics of Perspective

The Politics of Perspective

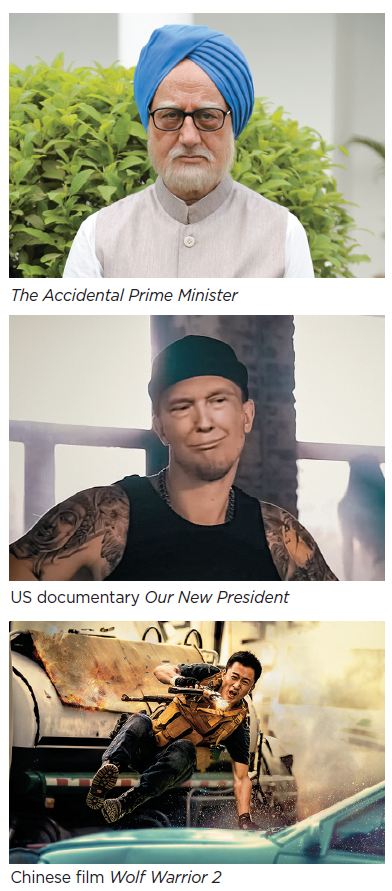

India seems to have started walking on a path where countries like the US, Russia and China have come a long way. Media reports in the US containing data obtained through the US Freedom of Information Act state that, between 1911 and 2017, over 800 feature films received support from the US government’s Department of Defence. Apart from war films for military propaganda, these have included blockbuster franchises like Transformers and Iron Man, where dialogues have been inserted or deleted to show the government or the army in a certain light. Most recently, a series of documentary features either chronicled Donald Trump’s rise to power, or the election tactics that helped him win.

New York-based filmmaker Maxim Pozdorovkin, whose film Our New President tracks how Russian state-sponsored media went all out to influence public opinion on Donald Trump ahead of the US presidential elections, says modern propaganda uses entertainment and social media to wilfully omit information or mislead. “Any populist medium will appeal to pre-existing biases. As long as internet remains the dominant medium of information distribution, and there is a profound crisis of education, you will tend to believe the messaging you are bombarded with without processing it too much,” Pozdorovkin says.

In his book Flicker: Your Brain on Movies, Jeffrey M Zacks, a psychological and brain sciences professor at Washington University in St Louis, provides case studies of how US politicians have historically used films to drive home their agenda. According to him, messaging through films have the potential to overpower conflicting information we might receive through, say, books and newspapers. Our brain, faced with what is called the source memory problem, sorts the information from all these mediums. “Most of the time, there is no pressure to sort correctly...This can lead us to accept information from a film as having come from more credible sources, particularly if time has passed.” Zacks says.

In Russia, according to investigative journalist Kseniya Kirillova whose work is focussed on analysing Russian propaganda, the Putin administration primarily uses TV and social media, while films paint a positive image of the country and its army. For instance, ahead of the presidential elections in 2018, a film called Going Vertical (titled Three Seconds in English) about a Russian Olympic sports victory over the US during the Cold War, apparently promoted Putin’s idea of patriotic superiority. It was made by Nikita Mikhalkov, an Oscar winner known for his nationalist views.

“Every government tries to create movies because it stirs strong emotions that a newspaper or traditional media cannot bring about. When Russia creates a positive image of itself on screen, it makes it easier for people to believe in their [the government’s] version of the truth,” Kirillova says, talking about how shows like Sleepers and cartoon series like Masha and the Bear have openly promoted government ideologies.

Then there is China, which, encouraged by its political leadership, is churning out movies (like Wolf Warrior 2, Amazing China and Operation Red Sea) that highlight the country’s achievements like military prowess and economic development. An article in the English-language Chinese newspaper Global Times points to how 5,000 “people’s cinemas” across China are designated to screen movies approved by the Chinese Communist Party. “Popular Chinese actors are converging in droves to serve as red avatars that instill positive energy in the audience,” the article states.

Back home, experts believe that filmmakers in India are also creating similar links with the government. “I believe that after Modi became the PM, there is a feeling across the entertainment industry that they would be able to gain something if they make pro-establishment content,” says Mukhopadhyay. ![g_112569_aninsignificantman1_1_280x210.jpg g_112569_aninsignificantman1_1_280x210.jpg]() A still from An Insignificant Man, about Arvind Kejriwal and the Aam Aadmi Party Explaining how the on-screen ‘angry young man’ persona mirrored people’s disillusionment with the political system in the 70s, Rangan says that, today, films like Uri reinforce a prevailing sense of patriotism. “In Uri, dialogues like “Yeh naya Hindustan hai. Yeh Hindustan ghar mein ghusega. Aur maarega bhi” (This is new India. It won’t hesitate to kill) got a thunderous applause from the audience,” he says. “Gone are the days when political films were tactful and diplomatic. Today’s films are portraying a national narrative that has a certain aggression. And that’s getting a good response.”

A still from An Insignificant Man, about Arvind Kejriwal and the Aam Aadmi Party Explaining how the on-screen ‘angry young man’ persona mirrored people’s disillusionment with the political system in the 70s, Rangan says that, today, films like Uri reinforce a prevailing sense of patriotism. “In Uri, dialogues like “Yeh naya Hindustan hai. Yeh Hindustan ghar mein ghusega. Aur maarega bhi” (This is new India. It won’t hesitate to kill) got a thunderous applause from the audience,” he says. “Gone are the days when political films were tactful and diplomatic. Today’s films are portraying a national narrative that has a certain aggression. And that’s getting a good response.”

Political journalist Rasheed Kidwai—who has written a biography on Sonia Gandhi and whose recent book Neta Abhineta explores the relationship between Bollywood and politics—believes that while filmmakers can capitalise on popular political sentiments, they must be cautious in making an open statement on contemporary political personalities, parties or issues. “You cannot create something that takes blatant political potshots and call it commercial cinema. Filmmakers must take a conscious call when it comes to such biopics and issue a disclaimer accordingly.”

Let Creativity Be

Meanwhile, filmmakers distance themselves from political motivations. Hansal Mehta, creative producer of The Accidental Prime Minister and a National Award-winning filmmaker, denies that the film was consciously timed. “Nobody makes a film to time it with elections. Those are just marketing ploys. A filmmaker has to tell a story, make a film.” he tells Forbes India. “Political films, by nature, will be critical. They will take sides. The audiences connect to the characters and their world, because these are stories of people who have lived among us.”

His opinion is echoed by Khushboo Ranka, director of An Insignificant Man (AIM), a documentary on Arvind Kejriwal and the Aam Aadmi Party that had a nationwide theatrical release in November 2018. She believes political films must be transparent about what is being made and who is funding it. “A good political film needs to accommodate many layers and opposing perspectives.”

Ranka admits that, right now, there is no accountability on behalf of the state machinery. The censor board, for instance, passes and rejects films without explanation. AIM, she recalls, faced long battles to receive a censor certificate. “The only thing that does not work is censorship of any kind. Even films like Thackeray that promote divisive politics should not be censored. All kinds of films should be allowed to exist in public imagination,” she says.

Mehta says freedom of expression must not be selective, and that even films that are critical of the ruling dispensation must be made. Like The Accidental Prime Minister, he believes that even books on PM Modi like The Paradoxical Prime Minister (written by Congress leader Shashi Tharoor) must be made. He says, “Whether we, as a country, are ready for mature political biopics will be tested only when the ruling dispensation, whoever it is, allows films critical of its administration to pass.”

copy_1.jpg) A poster of PM Narendra Modi, a biopic on the Indian prime minister, starring Vivek OberoiImage: Indranil Mukherjee / AFP / Getty Images

A poster of PM Narendra Modi, a biopic on the Indian prime minister, starring Vivek OberoiImage: Indranil Mukherjee / AFP / Getty Images Past Imperfect, Present Tense

Past Imperfect, Present Tense The Politics of Perspective

The Politics of Perspective A still from An Insignificant Man, about Arvind Kejriwal and the Aam Aadmi Party Explaining how the on-screen ‘angry young man’ persona mirrored people’s disillusionment with the political system in the 70s, Rangan says that, today, films like Uri reinforce a prevailing sense of patriotism. “In Uri, dialogues like “Yeh naya Hindustan hai. Yeh Hindustan ghar mein ghusega. Aur maarega bhi” (This is new India. It won’t hesitate to kill) got a thunderous applause from the audience,” he says. “Gone are the days when political films were tactful and diplomatic. Today’s films are portraying a national narrative that has a certain aggression. And that’s getting a good response.”

A still from An Insignificant Man, about Arvind Kejriwal and the Aam Aadmi Party Explaining how the on-screen ‘angry young man’ persona mirrored people’s disillusionment with the political system in the 70s, Rangan says that, today, films like Uri reinforce a prevailing sense of patriotism. “In Uri, dialogues like “Yeh naya Hindustan hai. Yeh Hindustan ghar mein ghusega. Aur maarega bhi” (This is new India. It won’t hesitate to kill) got a thunderous applause from the audience,” he says. “Gone are the days when political films were tactful and diplomatic. Today’s films are portraying a national narrative that has a certain aggression. And that’s getting a good response.”