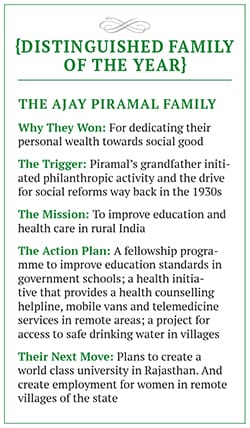

The Piramal family's purposeful philanthropy

For Ajay Piramal, wealth earned is not to keep, but to share. It is a legacy he's inherited from his grandfather, and one his children are upholding through their work with the Piramal Foundation

It is Monday afternoon and Saurabh Shukla, a qualified teacher, convenes a meeting with a primary school’s principal and senior staff. He has his Android tablet out and is sharing data which reveals that the school’s third and fifth grade students have seen a 10-12 percent improvement in their learning skills over a one-year period. As other teachers take in this data, Shukla talks about various ways in which the school can engage students in the curriculum, and improve their performance without overburdening them.

This meeting takes place, not in an air-conditioned or well-ventilated office in a city school, but in a single-storey rural setup in Soti, a village in Rajasthan’s Jhunjhunu district, five hours north of Jaipur. Only 60 students are enrolled into the Government Upper Primary School in Soti the village has an adult population of less than 1,000. But the school takes pride in being part of a programme that helps teachers enhance their ability to teach and interact with students.

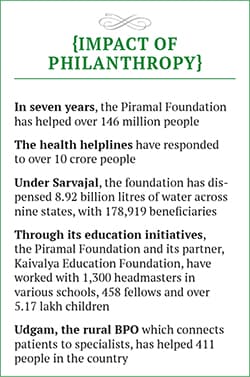

Shukla plays a vital role in identifying such learning trends, and in sharing that information with government schools like the one in Soti. The 24-year-old from Rajasthan’s Basti completed his Bachelor of Education from Dr Ram Manohar Lohia Avadh University in Uttar Pradesh a few years ago, and was worried about his future. That was until 18 months ago, when he was awarded the Piramal Fellowship, part of the Piramal Foundation for Education Leadership (PFEL).“We are influencing the lives of children who, in 10 years, will be ready to elect the next government. We have to make sure that they become responsible people,” says Shukla. He is one of the 150 fellows that are selected by PFEL every year from colleges and business schools to develop “on-ground leadership skills” and work in conjunction with schools in rural India. Now in its seventh year, the Piramal Fellowship has tied up with 1,300 schools in three states: Four districts in Rajasthan, all schools under the Surat Municipal Corporation in Gujarat, and 200 schools under the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation in Mumbai, Maharashtra.“This experience has transformed me. My father finds me more responsible and aware of community needs. Once I complete the [two-year] fellowship, which will be in six months, I’d like to create school development programmes, preferably in my hometown in Uttar Pradesh,” says Shukla, who currently works with eight government schools in Rajasthan.

PFEL, which runs under the aegis of the Piramal Foundation, started taking shape in 2007, when MBA consultant-turned-social entrepreneur Aditya Natraj approached chairman of the Piramal Group, Ajay Piramal, regarding funding for a project that would impart leadership skills to school principals. (Natraj had earlier worked with NGO Pratham, where Ajay Piramal is chairman.) “He [Ajay] heard me for 10 minutes and said, ‘Yes, okay, let’s try this out.’ What I found different about him was his risk-taking ability and his desire to bet on the youth,” says Natraj.

The outcome of that meeting was not just the launch of the Piramal Fellowship but also a Principal Leadership Development Program, a three-year Master’s training programme for headmasters from government-run primary schools. Piramal initially donated Rs 50 lakh towards these initiatives.

“We are privileged because of who we are. We are born in an affluent family and are educated. Not everyone has this luxury. We have a responsibility to share,” says 59-year-old Piramal, who was ranked 44 in the 2014 Forbes India Rich List, with an estimated wealth of $2.1 billion.

Natraj, who is now director of PFEL, says: “We were betting on the fact that young urban Indians would want to be a part of this initiative, and become nation-builders.”

It was a risk that paid off beyond expectations. In 2007, the first year of the fellowship, Piramal met graduates who were willing to leave their jobs in cities to work towards improving the country’s rural education needs. The Principal Leadership Development Program, which started the same year, was also a success: To date, over 1,000 school principals have taken this programme. And by 2010, Piramal had donated Rs 10 crore from his personal wealth to PFEL’s initiatives.

Apart from education, the Piramal Foundation conducts philanthropic activities in health care (Swasthya), water purification (Sarvajal) and rural empowerment (Udgam). Set up in 2007 by the Piramal Group, the foundation has a presence in 15 states in India, and claims to have positively impacted the lives of 146 million [14.62 crore] Indians.

“Our core principle is to not do more of what the government is doing. We don’t want to replicate any existing programme. We look for out-of-the box solutions to bring about sustainable change,” says Paresh Parasnis, head, Piramal Foundation.

Carrying Forward a Legacy

The Piramal family has been associated with philanthropy even before social responsibility became a part of corporate Indian’s lexicon. Much of Bagar in Rajasthan bears the stamp of Seth Piramal Chaturbhuj Makharia (grandfather of Ajay and his brother Dilip), who began his philanthropy work in the 1920s. “Piramalji (Seth) laid the foundation for the development of Bagar. Apart from schools and colleges, there are hospitals, water tanks, street lights, gaushalas (protective shelters for cows) and cremation grounds,” says Ravi Kumar Ojha, principal of Piramal Boys School in Bagar.

Seth Piramal is still very much a part of Bagar’s history. “He would meet with locals, sit with them and share stories,” says Ojha. He recalls anecdotes passed down from elders about how the senior Piramal would feed everybody on the train while travelling from Bagar to Sawai Madhopur (a district in Rajasthan).

“My grandfather was an inspiration. He was not a wealthy man, but shared a larger proportion of his wealth than others,” says Ajay Piramal. “If you don’t share your wealth you are doing a disservice.”

With the Piramal Foundation, the family is able to formalise and expand its philanthropy work to other parts of the country as well. Ajay’s wife, Padma Shri awardee Swati Piramal, who has helped influence public health policy, says, “Giving back to the hometown was always in our culture, but we realised that it was not enough.”

She recalls an incident that took place in 1984, around the time she had graduated from medical school, which underscores this point. “I was driving down Parel, [which was then] the mill land of mid-town Mumbai, when I saw a girl stricken with polio, struggling to walk with wooden crutches. That was my trigger,” she says. “What is the point of having all this knowledge if we can’t take care of these problems?”

At the time, the government’s National Polio Programme had yet to kick in. Swati and her college friends started a small clinic in Parel and made calipers out of plastic for children who were paralysed. “Within a decade, with no fresh incidents, we closed down the clinic,” she says. Over the years, Swati realised that philanthropy initiatives had to be conducted on a large scale to make any real difference. “Ajay bought that belief and thinking,” she says.

The next generation of Piramals—Swati and Ajay’s children, Anand and Nandini—are keen to carry on their great grandfather’s legacy, and build on their parents’ work.

Anand, who heads the Piramal Group’s real estate business, tells Forbes India that it was his experience as an economics student in the University of Pennsylvania that strengthened his resolve to give back to the community. In 2005, when he was on a summer programme in Italy, he shared his enthusiasm and fascination for the country with his teacher. “My Italian professor scolded me and said, ‘You should be singing paeans about Indian civilisation. Its richness is second to none.’ And from that moment, a single thought began to take root in my mind. India has known greatness, and is at an inflection point once again. In a patriotic impulse, I decided to return to India, and contribute in some way to the country’s growth and development,” says the 30-year-old.

Much like his father, Anand is inspired by the Bhagavad Gita. “The Gita advocates the concept of trusteeship of wealth. We were always taught that just trying to give back something to society is not enough. You must do it to contribute to your own spiritual development,” he says.

Road to Swasthya

When he was 19, Anand returned to India and started an NGO called DIA (Dreaming of an Indian Awakening). The NGO, which wanted to encourage youth to take on leadership roles, was the prototype for what would later become the foundation’s health initiatives. In 2008, before the Piramal scion left for Harvard for a three-year MBA programme, DIA’s work started slowing down, but it gave shape to the Piramal Swasthya Sahaika (PSS), an initiative that trains rural women in Rajasthan in basic health care. Tanuja Kanwar, in her early 30s, may not be a licenced health worker but villagers in Kalipahari, Jhunjhunu district, are comfortable discussing their ailments with her because she is one of them. As a part of PSS, she has a small clinic, stocked with basic over-the-counter medicine and a first aid kit. “I am satisfied and my mother-in-law is happy that I am able to contribute more to the community,” says Kanwar, who maintains a record of every patient who visits the clinic. When someone comes to her with an ailment, she contacts a call centre, manned by paramedics and counsellors, and run by of the foundation’s rural BPO initiative, Piramal Udgam. Based on symptoms and patients’ history, the call centre relays the best possible treatment and medication. While this works for common ailments, emergency and more complicated cases are referred to doctors and hospitals in the district.

Tanuja Kanwar, in her early 30s, may not be a licenced health worker but villagers in Kalipahari, Jhunjhunu district, are comfortable discussing their ailments with her because she is one of them. As a part of PSS, she has a small clinic, stocked with basic over-the-counter medicine and a first aid kit. “I am satisfied and my mother-in-law is happy that I am able to contribute more to the community,” says Kanwar, who maintains a record of every patient who visits the clinic. When someone comes to her with an ailment, she contacts a call centre, manned by paramedics and counsellors, and run by of the foundation’s rural BPO initiative, Piramal Udgam. Based on symptoms and patients’ history, the call centre relays the best possible treatment and medication. While this works for common ailments, emergency and more complicated cases are referred to doctors and hospitals in the district.

The Piramal Foundation has also set up 40 telemedicine centres in Assam, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Maharashtra that connect patients to doctors via videoconferencing facilities. According to Parasnis, who heads the foundation, this initiative has helped address major health concerns such as high maternal mortality rates (common in tribal communities in Andhra Pradesh), and diabetes (in Assam).

Six years ago, Swasthya started operating mobile health vans for people in remote villages who don’t have access to doctors or health care centres. A doctor and an assistant on board a van, equipped with diagnostic machines, travel from village to village. Swasthya also has a 24-hour health advice and counselling helpline in Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Assam and Andhra Pradesh. It is more an advisory service than a treatment centre.

Ajay’s daughter Nandini, who heads HR operations at the Piramal Group, also oversees (along with her husband Peter DeYoung) the foundation’s Sarvajal project, which provides people access to safe drinking water in parts of Rajasthan. Piramal Sarvajal runs a franchise model, where an entrepreneur buys a water purification machine (costing Rs 2-4 lakh) from the foundation, and sells clean drinking water—at 30 paise a litre—to villagers.

Putting Wealth to Use

A lot of the foundation’s work is concentrated in Rajasthan, but as it expands its reach to other parts of the country, Ajay Piramal has two questions on his mind: How to maximise the impact of his philanthropy? And how to innovate through new solutions? He tells Forbes India that it can only be done by scaling up in a cost-effective manner or collaborating with other like-minded institutions, NGOs and government bodies.

“Wealth is just a question of adding zeroes. If we can put it to use, people will remember it. Look at what the Tatas have done. The Bhagavad Gita says that you are the trustees of wealth it is not yours, you have to see that it is well used,” he says. “The purpose for the group is to do well and to do good.”

First Published: Jan 06, 2015, 06:56

Subscribe Now