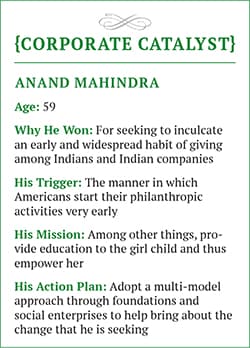

The Impact of Anand Mahindra's Nanhi Kali project

Of the many causes he espouses, the betterment of the girl child is foremost for Anand Mahindra. And with Nanhi Kali, he is helping you help them too

From the beginning, Hajiya Begum’s future looked bleak. Her mother could not forgive her for being a girl and deserted her. Her father died when she was young. It was left to her grandmother, who worked as a maid in a Hyderabad suburb, to raise her. Hajiya’s education remained in doubt, given that her grandmother made a meagre Rs 2,000 per month. And then, in 2006, everything changed. Hajiya, then in Class 4, became a Nanhi Kali. She continued her education and went on to score 93 percent in her Class 10 exams her photograph appeared in local newspapers. In the 2014 Board of Intermediate Exams (equivalent of Class 12), she scored 944 out of 1000 marks. Her dreams too have grown: She now wants to work in a company like Microsoft.

Over a thousand miles away in Sonthwa village in the Sheopur district of Madhya Pradesh, girls don’t study beyond Class 5. They are typically married off at 13. Parina Meena, born to parents who could barely rustle up Rs 2 lakh a year working on agricultural farms, faced a similar eventuality. Parina loved studying but dreaded the day she would be married off. But her fears dissipated when she became a Nanhi Kali, on reaching Class 4, in 2006. She went on to get 92 percent in her Class 10 exams. She now wants to become an engineer.Hajiya and Parina are two of the over 100000 Nanhi Kalis who have blossomed in gloomy circumstances. And for this, they have Anand Mahindra to thank.

Nanhi Kali (‘little bud’ in Hindi) is an initiative conceived by Anand Mahindra in 1981. It seeks to educate and empower the girl child by taking care of her needs, including hygiene, uniforms and tuition fees. The project was conceived after Mahindra returned to India from the US and began working at Mahindra Ugine Steel Company.

All he could manage was an initial funding of Rs 15 lakh. “I did not have the resources to write a big cheque then,” he recalls. Instead, he used ingenuity. “While studying there [in the US], I noticed a widespread culture of giving back to society, and philanthropy started early—as soon as people began earning. They made sure a percentage of their salary was spent on a good cause.”

Mahindra decided to structure Nanhi Kali as a platform that would inspire Indians to give for a cause. It was structured such that a donor can even contribute Rs 10 per month. Consider that even a Rs 1,000-a-month donation, taken over a year, is good enough to meet the full cost of a girl’s education and many of her other needs.

Today, there are 10,000 individuals who contribute to the initiative, apart from 40 large corporations and 500 smaller institutions. And the impact is felt by Nanhi Kalis across eight states.

The objective, says Mahindra, is to spread the culture of giving. He is not a fan of what he calls “billboard givers”, referring to the likes of Bill Gates and Warren Buffett who have donated billions of dollars for a cause. “In the Indian context, we need a billion givers rather than a billion dollars by a single giver. An early and widespread culture of giving is what suits us better,” he says.

In 2007, he became a front-runner in another cause—by becoming one of the earliest movers among corporate bigwigs to practice corporate philanthropy. As managing director and vice-chairman of Mahindra & Mahindra, he committed that the company would contribute 1 percent of its net profit to philanthropy. In 2012-13, the Rs 43,962-crore company spent Rs 89 crore in corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities in 2013-14, the amount went up to Rs 121.15 crore. (In April, 2014, the government ruled that companies with sizable businesses would need to spend at least two percent of their net profit on CSR.)

“M&M’s focus areas when it comes to CSR are education, especially for the girl child and for the economically/socially disadvantaged sections of society environment, with special emphasis on green cover and water conservation and public health, including sanitation,” says Rajeev Dubey, president (group HR, After-Market & Corporate Services). “Anand Mahindra is the prime moving force when it comes to the strategy of all our CSR activities.”

This passion for education is rooted in Mahindra’s personal experience and the values his mother gave him. “He says his mother always told him that you can know a person if you know his childhood. He strongly feels education can transform future citizens and thus the country. He also believes that a good teacher can bring unparalleled transformation to society,” says Manoj Kumar, CSR advisor to M&M, who has worked with Mahindra for over a decade. Kumar is also CEO, Kallam Anji Reddy Chair, Naandi Foundation.

Mahindra’s role with CSR is not limited to merely crafting its vision and making funds available. He is deeply involved in its execution. “He insists that we run CSR activities just as we do our business: Run it efficiently, measure the impact and scale it up,” says Sheetal Mehta, chief of CSR at M&M.

He also gives unrestricted access to members of his CSR team. “Today I have more access to him than what I had as a product manager of Bolero [an M&M auto product] many years ago,” says Mehta. His review meetings for CSR work are as detailed and strenuous as any involving his businesses, she adds.

As chairman-for-life at Naandi Foundation, which was set up by the late Anji Reddy, former chairman of Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, Mahindra has spread his philanthropic wings beyond the confines of his own company. “In 2004, Dr Reddy wanted Mahindra to be a part of Naandi Foundation. He wrote a long mail about the foundation and its focus on education, empowering small farmers and drinking water. In less than five minutes, Mahindra responded saying he is on board,” recalls Kumar. After just two board meetings, Mahindra had devised a strategy to scale up the Foundation. From then on, Dr Reddy and Mahindra embarked on a journey of mutual admiration. Mahindra was made life trustee of the Foundation in 2005 and chairman-for-life in 2013, after Dr Reddy passed away.

Naandi Foundation’s Naandi Education Support Training initiative offers after-school remedial support to children in government primary schools by identifying students who need special tuition. Mahindra ensured the project had very strong partners, including Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, Sir Ratan Tata Trust, Google Foundation, World Bank, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories and, of course, M&M. “We deeply value our collaboration with Anand Mahindra and applaud his dedication to creating positive outcomes for India’s children,” says Barun Mohanty, international managing director, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation.

Over the years, Mahindra’s approach to philanthropy has kept in tune with time. Of late he has begun to look at social enterprises (which are structured to make profits that, however, do not flow back to the funders) as a better vehicle to do good. “A good proportion of Indians are neither too poor nor belong to the middle class yet. They cannot be left either to the market forces or be condemned to dole. We need a mezzanine policy, and social enterprises fit in perfectly in that role,” says Mahindra.

His first experiment with a for-profit social enterprise was Naandi Community Water Services Ltd in a joint venture with Danone (the Spanish-French food products company) where Mahindra is the single largest investor. The project has set up over 360 water treatment plants in India to supply pure drinking water to rural communities. This is done by entering into an agreement with the local panchayat.

The company puts up a treatment plant (Danone offers the technology) and local youth are trained to maintain and manage it. Villagers are required to buy the water at Rs 4 for 20 litres. “People are happy to pay for clean water. In a few years, these plants will become self sustaining and the surplus generated will be ploughed back to the community,” says Kumar. Three million people have access to pure drinking water because of it, he adds.

Mahindra’s other experiment with social enterprise has been in the area of skill building.

Coffee grown in Araku Valley, located in the Eastern Ghats of the Vishakapatnam district of Andhra Pradesh, has a special flavour (hence, value). However, the area had a high Naxalite influence and local tribals lacked the skills to process the coffee, brand it and market it. When Mahindra learnt about it, he helped form a coffee co-operative (Mahindra is the single largest funder and has roped in people like Satish Reddy, chairman, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories). Processing facilities were set up, quality control measures were introduced and the Araku Coffee brand was created and promoted.

The results are beginning to show. Today, 100 tonnes of coffee are sold to international buyers and about 25,000 acres are under coffee plantation. The co-operative has become the largest organic coffee farming effort in the world. “The initiative has improved the lives of 1 lakh tribals in the area and about 10 percent among them are lakhpatis. It has empowered women farmers and, most importantly, eliminated the Naxalite influence significantly,” says Kumar.

These days Mahindra is bullish on the concept of shared value. “It is a more sustainable form of philanthropy where businesses create a shared value rather than issuing a cheque,” he says. “Writing a cheque will vanish if profits vanish.”

Shared value is the foundation of the group’s Mahindra Rise campaign—driving positive change by doing well and doing good.

Some examples: M&M’s Samriddhi Centres provide fee-based service to farmers on technology, soil testing, irrigation and modernisation of agricultural practices. The group’s housing finance business is offering products that provide small ticket loans for each stage of housing construction. Its insurance arm has designed products targeted at the emerging sections of society, inspired by the concept of shampoos in sachets.

“Anand’s philanthropy is exemplary in inspiring other corporates and business leaders to give by way of personal engagement that assures the outcomes are met with credibility and impact. I have seen this at close quarters through the work at Naandi Foundation and the social enterprises I co-support with Anand such as the Araku Coffee Project,” says Satish Reddy.

His personal engagement in terms of time spent is significant. “He attends 20 board meetings for CSR-related activities every quarter. Each meeting lasts at least half a day. He also holds brainstorming sessions when required. A simple calculation shows that he spends over 30 full days on philanthropy-related work,” says Kumar.

As a business leader, he has the responsibility to set an example. “But we are on the right track,” Mahindra says. “When we were a poor country, a person’s social hierarchy was derived from his personal wealth and conspicuous consumption. Post-liberalisation and the growth it offered, it was how well your company was doing. Now we are heading to a far more virtuous way, which is how much of your wealth are you giving back to society.”

And this is true not just among the rich. People across the board are giving and, also, moving to the next level. That is “strategic giving”, or giving for a focussed cause after fully understanding it, he says. And this can only be good news to the many Hajiyas and Parinas of India.

First Published: Jan 08, 2015, 06:37

Subscribe Now