How 'Desh' Deshpande is helping Indian NGOs scale up

Tech billionaire Gururaj 'Desh' Deshpande is helping NGOs scale up and sustain philanthropy initiatives on their own steam. His formula for self-reliance is relevance followed by innovation

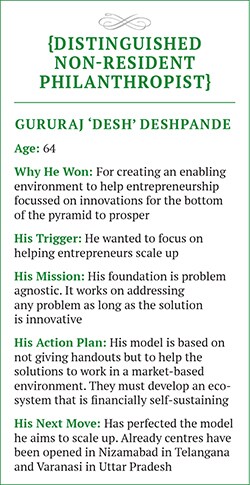

In 1996, when venture capitalist and entrepreneur Gururaj Deshpande started his first innovation centre at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston, he was clear about two things. First, his philanthropic activities would not involve merely funding grants. Second, he would approach his giving in much the same way as he approached his life as an entrepreneur. “An idea does not have an impact unless it is directed at some burning problem in the world,” the 64-year-old tech billionaire tells Forbes India during a phone conversation from Boston.

Deshpande applies this core tenet to every project he works on, including Akshaya Patra, a non-profit organisation that is very close to his heart. He is the chairman of the US chapter of the NGO, which provides free lunch to more than a million schoolchildren across India. The scale of its operation at Hubli, Karnataka, is impressive.

At 6.30 am, the town’s largest industrial kitchen was busy preparing mid-day meals for 1.75 lakh schoolchildren in 800 government schools across the districts of Hubli and Dharwad. The building, spread over a three-acre campus, is fitted out with industrial-sized tumblers to prepare rice and sambar. It’s also equipped with its own heating plant to provide fuel needed for cooking. That’s 14,000 kilos of rice, 12,000 litres of sambar and 5,500 litres of milk every day. By 7.30 am, trucks are loaded with food.

Feeding 1.75 lakh children costs about Rs 15 lakh a day, and while the government helps with rice supplies from the Food Corporation of India, the programme relies on donors to fund the bulk of its operations.

Partnering with initiatives like Akshaya Patra has made Deshpande—or Desh as he is popularly called—something of a messiah in his hometown, Hubli. A decade ago, the billionaire and his brother-in-law, Infosys co-founder NR Narayana Murthy, donated $1 million (then Rs 5 crore) to set up the kitchen. It remains, to date, the largest of all the 18 kitchens across India in Akshaya Patra’s network.

But Deshpande does not contribute any of the funds needed for the day-to-day running of the kitchen. An entrepreneur to the core, he is clear that most organisations must be able to support themselves. He does not want to be seen as a mere grant maker. “I chair its fundraising committee in the US, but don’t contribute to daily expenses,” he says.

This philosophy sets the tone for how the Deshpande Foundation, which he founded with his wife Jaishree in 1996, approaches its philanthropic activities. It may have started out by supporting initiatives in the US but, in 2007, the entrepreneur decided to expand its reach to his birthplace, Hubli. One of its primary goals is to support entrepreneurship at the bottom of the pyramid.

Spend time in the town, and it becomes apparent that the foundation has a refreshingly different take on what philanthropic organisations need to do to succeed. There’s active support for ideas that can make a difference to society. And, most crucially, it helps innovators and other organisations scale up these ideas.

It’s a learning that has come out of Deshpande’s experience of over three decades as an entrepreneur. This enables him to examine his philanthropic activities with the same lens through which he looks at entrepreneurship. “As an entrepreneur, you need to identify a problem and scale up. The same holds true for this (philanthropy) space, except that people are not very good at scaling up. That is where we step in,” he says.

When the foundation started operations in Hubli, locals slotted it as a donor.

“People would come to us and tell us that they didn’t have electricity or that the roads were not good. And I would say to them, ‘Well, I don’t even live here. This is not something that I can solve’,” says Deshpande.

It was also not something he was interested in solving. Over the years, he had learnt that you needed innovation and relevance for your idea to have an impact. But in the non-profit space, the equation had to be reversed: Relevance first, and then innovation.Naveen Jha, CEO of the Deshpande Foundation, India, says that it is in the process of expansion that an idea is severely tested. “Scale removes all the inefficiencies from the system and allows the organisations we fund to build a self-sustaining ecosystem,” he says.

With this in mind, Deshpande started an innovation centre at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1996, the same year he started his foundation. He called the centre Sandbox—a place where entrepreneurs get guidance and support so that their ideas can come to fruition, and grow. He doesn’t mind if people fail, but what the Sandbox frowns upon is having an idea that ultimately cannot pay for itself.

In 2006, the Hubli Sandbox was set up. It was envisioned as a place where social entrepreneurs in the Hubli-Dharwad area could come with their ideas and experiment. Over the last eight years, the foundation and Sandbox together have funded 135 ideas since inception and seen 10 achieve significant scale.

“What sets us apart from other philanthropic foundations is that we are agnostic to an idea,” says Jha. The Deshpande Foundation encourages innovation in all areas, and does not limit itself to any one field such as health or education. “There have been times when we have been very sceptical of ideas, but we still give people the support needed to see if they can work it out.”

Jha cites the example of a student who wanted to create an SMS-based system that would alert citizens on when they could access municipal water in their homes. Though the foundation was doubtful about the use of such an innovation, Jha and his team supported the idea. Much to their surprise, the initiative gained traction in Hubli and Bangalore. “People are paying a modest Rs 15 for the service because it has made a clear and noticeable difference to their lives,” Jha points out.

Farmers in the villages surrounding Hubli, too, have benefited after the Deshpande Foundation lent its muscle to the BAIF Development Research Foundation’s Wadi, which helps farmers in the district increase their revenues by planting fruit, teak and eucalyptus trees.

At a cost of Rs 30,000, it would help farmers grow fruit (mainly mango) trees at regular intervals in a small area of their plot. As this effort doesn’t take up much space, the farmer is free to plant his usual crop in other parts of the field. In addition to this, BAIF would also plant eucalyptus and teak trees on the periphery of the land. These could then be sold for extra money.

What ailed the initiative, however, was the lack of scale. BAIF would work with a few farms for free, waiving the Rs 30,000 fee, and then wait for more funds to come in before it could start with a new lot of farms. “It was a slow process and in the

five years that we have been active in Hubli, we worked with 500 farmers,” says ML Kulkarni, who heads BAIF’s initiatives in the district.

When the Deshpande Foundation stepped in two years ago, it began working with BAIF on bringing the cost down from Rs 30,000 to Rs 10,000, by tying up with seed and fertiliser companies. It also made sure that the farmer worked on his field and did not leave everything to BAIF.

With the reduction in price, the foundation was happy to provide Rs 7,500 for each acre planted while the farmer contributed Rs 2,500. As a result, the model has been able to help 5,000 farmers in Hubli.

Irfan, a 36-year-old farmer who owns an acre of land, is one such beneficiary. The soil, far away from any irrigation source, is red and rocky—hardly the kind of high-yielding fertile variety that helps cotton plantations thrive just a few kilometres away. “I would make about Rs 40,000 a year from my one acre,” says Irfan, who goes by a single first name. That’s enough to feed him, but there is not much left for anything else. This has changed with the Wadi programme. His income has doubled since he started planting fruit-bearing trees at regular intervals. It’s organised in such a way that he can continue growing pulses.

Another significant organisation that is supported by the foundation is the Agastya International Foundation, a Bangalore-based non-profit educational trust which teaches science to rural children. Deshpande donated funds so that Agastya could set up an impressive museum and learning centre in Hubli. Every day, children are brought in from surrounding districts and shown scientific experiments. This, Deshpande argues, goes a long way in inculcating a scientific mindset. Out of a total of 10 Intel Science Awards, three went to children from schools that worked with Agastya.

Back at the Akshaya Patra kitchen, the trucks laden with food are ready to depart to various schools in the district. All operations at the facility come to a close it will open again at 2.30 am the next day. The menu is posted on the kitchen wall. With sambar being served every day, the kitchen is careful to vary the taste and the vegetables used while preparing it. The rice is also varied some days it is plain boiled other days it is made with lemon. Each batch is given a number in the event of a problem, it can be traced back to the source.

To date, Deshpande has spent Rs 80 crore on his foundation’s activities in Hubli alone. This does not include capital expenditure such as office space and employee salaries. And buoyed by the success and impact in Hubli, he’s gearing up to do what he does best—increase the scale of his activities.

He’s already launched two more Sandboxes, one in Nizamabad in Telangana in collaboration with Phanindra Sama of redBus fame and Raju Reddy of Sierra Atlantic, and another in Varanasi with Dilip Modi, CEO of Spice Mobility. “If we can support people who take a bottom-up solution to problems in the sector, we will be able to make a far bigger impact than a top-down approach,” says Neelam Maheshwari, director, grants, at the Deshpande Foundation.

What sets Deshpande apart is his belief that the solution has to come from the people who will benefit the most. He argues that in the non-profit space, recipients are often not given a voice, and solutions are thrust upon them. That, he says, is the wrong way. Gururaj Deshpande prefers doing the exact opposite.

First Published: Dec 30, 2014, 06:27

Subscribe Now