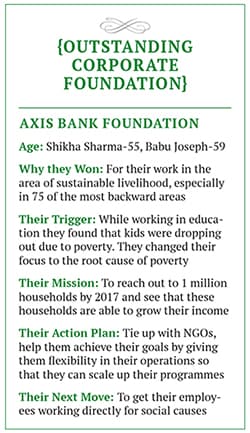

Fixing The Big Picture: Axis Bank Foundation

By shifting its focus from education to the larger issue of poverty, Axis Bank Foundation is proving effective in addressing the livelihood issue in underprivileged India

Why were children still dropping out of schools, wondered Babu Joseph, executive trustee and CEO of Axis Bank Foundation (ABF). It was 2010. His organisation had been working closely with NGOs in some of the poorest areas of the country, but to little avail. Since 2006, when ABF was set up (as UTI Bank Foundation before the name change to Axis Bank took place in 2007), education had been its primary focus but, over the years, the results had not been encouraging. “We often saw children dropping out of school and we found that poverty was the reason for that. These were areas which had not seen any growth in terms of income as well as development,” says Joseph.

Among the worrisome areas was Jharkhand, where ABF was working with the Nav Bharat Jagriti Kendra, an NGO that concentrated on supplementary education for classes 8 to 10, particularly in courses related to maths and sciences. The NGO had found that kids were dropping out as their parents were continually on the move in the search for livelihood.

A similar trend was observed in the slums of Delhi where kids had to leave school since families were returning to their native places due to lack of jobs and looking for work on the farms.Joseph phoned Shikha Sharma, managing director and CEO of Axis Bank, and asked for a meeting. This was in June 2010, a busy time for Sharma. It had only been a year since she had taken up the top job and already had her plate full. But he got his meeting and explained to her that there was an increasing trend in the dropout rate of kids and that vitiated the foundation’s focus on primary education. Sharma told him to dig deeper and assess the reasons behind this trend. Within the next three months, and after talking to various people in the field, Joseph was convinced about the link between the dropout rate on the one hand, and poverty and migration on the other.

The shift in focus to sustainable livelihood—and tackling the problem at the root—was the obvious solution. “Once people find stable jobs, they will not have any problems sending their kids to school,” Sharma told Joseph.

The next steps were clear: Joseph and his team engaged with four NGOs who were working on sustainable livelihoods. He started with Development of Humane Action (Dhan) Foundation, a Madurai-based organisation that works on improving livelihoods using innovative themes. Among those initiatives is the cleaning up of the lakes and tanks so that women do not travel distances to fetch water. Through this programme, ABF worked with 30,000 families, training the women through self-help groups in kitchen gardening and animal husbandry, among other areas.

“The focus for Axis Foundation is that we want to see the income of these people grow and see how we can help them achieve this. We work very closely, and on a long-term basis, with our NGOs so that these goals can be sustainable,” says Sharma. As with Dhan, ABF outsources its programmes to other NGOs that are experts in their fields. How it works is, ABF identifies a cause and connects it to the appropriate NGO, and, thereafter, monitors the work. The association is similar to that in project finance where targets and achievements are well-rewarded. For instance, ABF has even worked with NGOs such as People’s Rural Education Movement that work on making tribal youth employable.

Joseph and his team have identified 23 programmes for sustainable livelihood and already reached 3.27 lakh families. Till date, ABF has contributed around Rs 119 crore towards the cause which accounts for 70 percent of its total contributions since 2006—the balance is for education.

In 2012, ABF started working closely with Srijan in Rajasthan which trains women in animal husbandry and goat-rearing. It also helps women collect custard apple from the wild and sell them. And here, the organisation’s ingenuity is well showcased. Since the fruit has a limited shelf life, the NGO decided to deep-freeze the pulp and supply it to ice-cream makers through the year. “But deep freezers and machines required money,” says Ved Arya, founder, Srijan. They had approached the government but the process was too long-drawn. ABF, meanwhile, was willing to give them the money immediately. “ABF is receptive to ideas,” says Arya. “They are very sensitive to the requirement of the people on the ground.”

It also helps that the man helming the project has had his ear to the ground throughout his career. Joseph is a career banker and one of Axis Bank’s oldest employees. A post-graduate in agriculture and horticulture, he took the SBI Probationary Officers exam for bankers and joined the State Bank of Travancore in 1979. After heading the Pune branch, he moved to UTI Bank in 1995, and subsequently got transferred to its headquarters in Mumbai in 2005. There, he started managing the bank’s SME business and got involved with agriculture, microfinance and rural banking, among other activities that gave him exposure to the agricultural business.

He also became aware of the problems faced in underdeveloped areas and he starting thinking about improving the lives of those untouched by growth. The key to their development, he realised, was education. Joseph got the opportunity to make a difference when ABF was set up in 2006 as UTI Bank Foundation. In 2010, he joined the Foundation as executive trustee and CEO and, since then, he has trained his sights on addressing the larger livelihood problem.

ABF has set a target of providing sustainable livelihood to one million households by 2017. “As agriculture income goes up, it becomes easy to scale up the programme,” he points out. Though ABF promises the NGO that they are committed for the long term, for around three to five years, funds are released on a quarterly basis. And the scalability of the programme is based on the achievability of its targets. But measuring its impact is not easy and, here, the quality of data gathering is crucial. For this, it has hired Tata Institute of Social Sciences to conduct impact studies for many of its programmes. One of its main objectives has been to provide livelihood through agricultural means and, to that end, NGOs aim to create rainwater harvesting structures that would raise the water table. This helps farmers make land cultivable and even harvest more than one crop.

There are many other areas where ABF can make an impact, says Joseph. For instance, through Navjeevan, the Foundation has sponsored a school in Kapri village, in Murbad, Maharashtra, which children of sex workers attend along with other students from the village. The NGO was started in 1996 and started working with ABF in 2010. “ABF has not just given money to us but they are completely involved with our cause. ABF helps us utilise money in the most scientific way,” says retired Reverend Dr Thomas Mar Theethos.

While the focus of ABF today is livelihood and education, its oldest programme is associated with highway trauma care. In fact, Axis Bank has worked on this cause even before ABF was set up. As Joseph points out, though highway trauma care accounts for only one percent of its total spend, “even if the money contributed to the cause appears low, the impact of the contribution is enormous”.

In 2004, Axis Bank (then UTI Bank) was already involved in philanthropic work when PJ Nayak, the then chairman and CEO of the bank, came across Subroto Das, a social worker from Baroda, who was helping highway accident victims through his helpline, Lifeline Foundation. Nayak was impressed by the cause and decided that the bank should partner Das in this endeavour. Over the last 10 years, the helpline has reached 22,000 accident victims, having mapped highways in Gujarat, Maharashtra, Kerala, Uttaranchal and West Bengal. “Had it not been for ABF [then UTI Bank], we would have only been doing our work in Gujarat. ABF helped us scale up,” says Das. “They brought in good governance and transparency within the Foundation and I think it is because of their support that we have been able to attract a lot of attention from the government and even influence policy at national and state levels on trauma management, ambulance standards and creation of a uniform emergency helpline across various states of India.”

Unlike some other corporations who are happy to set up infrastructure and then step back, says Das, ABF gets involved in the day-to-day activities of these NGOs and even takes care of operational expenses. The NGOs are able to scale up and plan for the long term and that is what makes all the difference.

As Sharma puts it, “We have taken upon ourselves to provide at least a million sustainable livelihoods by 2017, with a commitment that at least 60 percent of the beneficiaries we support are women. The officers of our bank would also play an important part in carrying out our duties as a responsible corporate citizen.” Consider that when ABF decided to provide blankets to flood victims, Axis Bank employees were involved in distributing them to households located in the interiors and difficult to reach.

Sharma is clear that she wants the employees to get personally involved in community work. And when the foundation is that strong, it bodes well for the rest of the building.

First Published: Jan 02, 2015, 07:42

Subscribe Now