Punjab Deputy CM Has A Plan For Change

Deputy CM Sukhbir Badal has the right ideas to fuel Punjab's growth, but has an uphill task

It is a chilly winter morning in Chandigarh. Pramod Kumar is in deep discussion with retired judge KS Grewal and Additional Director General of Police SK Sharma at a roomy office in the Institute for Development and Communications on how to stop harassment of women in public places. “Perhaps,” he suggests, “we should suspend driving licences of those who harass women, or deny police verification for passports.” Justice Grewal says that the issue is complex, but promises to think of ways to tackle it. Pramod Kumar is chairman of the Punjab State Governance Reforms Commission (GRC), currently the fount of ideas to improve governance in the state.

In 2009, Sukhbir Singh Badal (Deputy Chief Minister, Shiromani Akali Dal president and son of chief minister Parkash Singh Badal) invited Kumar to head a proposed GRC. Kumar was sceptical he had seen governments come and go without anything changing. But when Badal told him that he could decide who would be on the commission, and that the government would take continuous action on its recommendations instead of waiting for its term to end, Kumar accepted. He says Badal’s brief was simple: “Develop your own terms of reference keeping in mind our vision.”

One of the first things the GRC recommended was reducing the number of affidavits citizens required for many services, from around 200 to less than 20. The government acted on the suggestion immediately, saving, by Kumar’s estimate, a collective Rs 600 crore. Another initiative based on voter identity cards helped weed out about 40 percent false pension claimants, saving the state Rs 400 crore. These were the first signs—in 65 years—of a shift in the way Punjab’s politicians approached administration.

A mandate for change

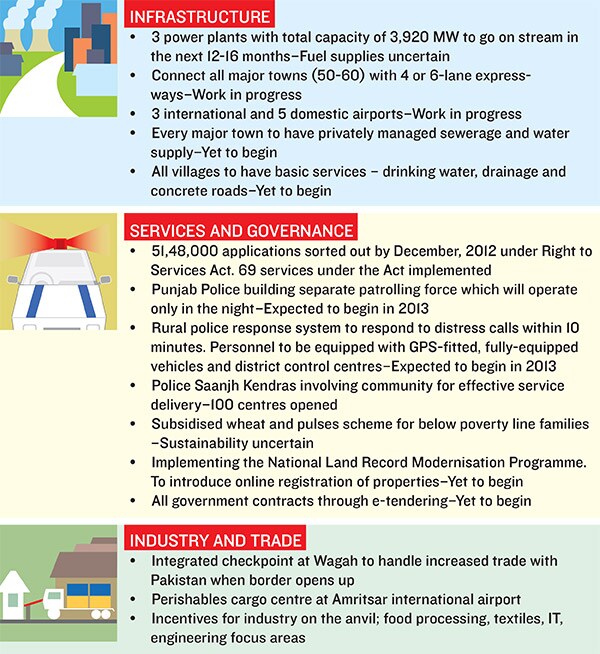

In 2012, the Akali Dal-Bharatiya Janata Party alliance created Punjab history when it became the first ruling government to win the state elections Sukhbir Badal is widely acknowledged as the architect of the victory.

The younger Badal is one of a handful of regional political leaders—Narendra Modi in Gujarat, Shivraj Singh Chauhan in Madhya Pradesh, Nitish Kumar in Bihar, Pawan Chamling in Sikkim, Naveen Patnaik in Orissa—attempting to shift the political discourse to economic growth, human development and governance. Traditional factors such as caste, religion and identity still dominate their realpolitik, but the image they seek to project is that of progressive change agents. Barring Patnaik (born in 1946), all belong to the post-Independence generation. Sukhbir Badal, an MBA from California State University in the US, is the youngest of the lot at 50. A close friend of his, who does not want to be identified, describes him as “cosmopolitan”. His Facebook page lists his personal interests as sculpture, bhangra and travelling, and one of his ‘favourite quotes’ is “As long as your [sic] going to be thinking anyway, think big.”

‘Identity, dignity, productivity’

In front of Mohali’s Phase 8 police station, sits a brightly-painted building. Two young policewomen sit in a glass cabin that resembles a bank counter. The neat, air-conditioned hall has a waiting area and corner desk for the person in charge. All staff are in cream-and-brown uniforms and wear ties. This is one of 100 police outreach centres, managed jointly by police officials and citizens, which provide 20 time-bound services. The shortest wait period is five days (permission to use loudspeakers), and the longest 60 days (copy of untraced report in cases of theft).

Mohali’s Senior Superintendent of Police, GS Bhullar, a twice-decorated Punjab Police Service officer, explains: “People are wary of coming to police stations. Now they do not have to step into one for services such as passport verification and applying for various permissions.” (He admits, however, that this centre is yet to become popular.) These services are among the 69 brought under the Punjab Right to Services Act in October 2011, along with several revenue, health, water and electricity services.

Kumar says the idea was to “protect the identity and dignity of people and improve productivity”. Sukhbir Badal says, “Corruption only happens when people have to interact with a government official. If you eliminate the interaction, how can corruption happen?”

The government is increasingly using technology to reduce face-to-face interaction. For instance, all government procurement is now done through e-tendering. Soon, people will be able to file FIRs to the police online, and then track the status of complaints.Yet: “The level of corruption in Punjab is unprecedented,” says SS Jodhka, professor of sociology at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, adding that, “The de-professionalisation of [the] police is most dangerous in Punjab.” An IAS officer in the state (who prefers not to be named) says that local Akali Dal leaders influence police postings, frequently abuse power, and that in many offices, corruption is institutionalised. Other causes for crime, he says, are unemployment and an alarming increase of drug abuse.

Unemployment was 42 for every 1,000 educated individuals, compared to the national average of 25, according to the 66th round of the National Sample Survey. The state economic survey, 2011-12, says that drug abuse is emerging as a major problem.

Surinder Kler Shukla, who teaches political science at Panjab University, is just completing a study, ‘What do the youth want?’ Her research reveals high drug and alcohol abuse among young people. It found that 80 percent of boys and girls between 18 and 23 use drugs or alcohol fairly regularly. She says, “When I travel, people I meet often tell me ‘nazar lag gayi hai Punjab nu’” [Punjab has been blighted by the evil eye].

Crime often has patronage. Recently, a girl committed suicide in Badshahpur village in Patiala district when police did not take any action for a month and allegedly threatened her after she complained she was raped. In early December last year, an Akali Dal leader was accused of gunning down an assistant sub-inspector of police in Amritsar after the cop asked him to stop harassing his daughter.

Badal says crime cannot be stopped what matters is the response. The government is building a dedicated night patrol force and a rural rapid response force equipped with modern technology such as GPS. The aim: Reduce response time to 10 minutes anywhere in the state. It will also set up a 24-hour helpline under the home minister’s office (Badal holds the portfolio) with an additional director general of police in charge. He says the government is also putting in place a new policy: If a woman complains, a police officer of a rank not less than deputy superintendent will have to go to her home to record a statement: “No girl will have to go to a police station anymore.”

Wooing industry

Badal says, “We are an agricultural state and our people are entrepreneurial. [But] we do not have a port to attract people. We do not have natural capital. So we are not a natural [investment] destination.”

To change this, he is hoping to create ‘world class’ infrastructure. “There will be an airport within an hour’s drive from anywhere in Punjab. We will also link every major and medium town in the state with a four- or six-lane expressway.” More immediately: “By the end of 2013, we will be a power surplus state.”

Last year, Punjab’s unrestricted demand was 9,500 MW and the state managed to supply 8,500 MW, according to state power secretary Anirudh Tiwari.

Badal is betting mainly on three new power projects: GVK’s 540 MW plant at Goindwal Sahib, Vedanta’s 1,980 MW thermal generation project at Talwandi Sabo, and L&T’s 1,400 MW station at Rajpura. GVK’s first unit (270 MW) is scheduled to start production in March 2013, and over the next 12 to 17 months, 3,920 MW of new capacity should go live, which will help the state overcome its 10–12 percent demand-supply gap.

But the biggest problem hobbling India’s power producers could hit these projects too: Uncertain fuel supplies. Coal for GVK’s unit was to come from the company’s mine in Jharkhand. But coal production has not begun: GVK has not been able to acquire land. The state has been asking the Centre for a six-month supply until the problem is sorted out. “The Government of India’s response has not been very encouraging, but we are hopeful,” says Tiwari. The other option is to import coal, which will increase cost and delay the project. Similar issues plague Vedanta’s and L&T’s projects. As Tiwari says, “The choice for the people is going to be whether they want [delayed] power or expensive power.”

Punjab, however, is going ahead with upgrading the distribution and transmission network. It is building a 400 kV transmission system for efficient distribution, and separating agricultural and domestic supply using exclusive feeders. Tiwari says it hopes to cover 85 percent of agricultural connections by the next paddy season.

Good infrastructure, better cities, cleaner villages and improved governance could attract investors. But for sustainable growth, it will be crucial to improve public finances and build an inclusive, democratic society.  Sharpening paradoxes

Sharpening paradoxes

Pramod Kumar nails down the state’s dichotomies: “Punjab has the most globalised population but is the least globalised state. It has the most developed agriculture sector but least integrated to industry.”

Punjab’s finances are precarious. It is likely to cross its borrowing limit of 3.5 percent of state GDP this year. Three-fourths of its revenues go towards fixed payments.

Populism costs money too: In mid-2011, newspaper reports, quoting replies to RTI filings, said Punjab Civil Supplies Corporation diverted Central funds to sustain the government’s flagship welfare scheme for the poor, the ‘Atta-Dal Scheme’, which supplies cheap wheat and dal to about 15 lakh families. The government was reported to owe over Rs 1,100 crore to four departments at the time. Unless it finds ways to improve its finances, Punjab’s economy will struggle.

Badal doesn’t believe austerity is the answer: “What we need to do is look at the resources and if it is X, target to make it 10X if you go the other way, you will de-accelerate the economy.” He illustrates: “If you have one egg instead of two, the demand for eggs will go down. If eggs don’t sell, the poultry farms will collapse, if the farms collapse the feed mills will collapse and if the feed mills collapse then the farmer will collapse. That means you are collapsing the whole thing. What you need is if you [had] two eggs, now you should have three. Then the downstream goes up. That’s what we did.”

The state did manage to improve some revenues. Value-added tax receipts doubled, from Rs 5,342 crore in 2007-08 to Rs 10,017 crore in 2010-11. Excise collections went up from Rs 2,101 crore in 2009-10 to Rs 2,373 crore in 2010-11, the state economic survey shows. But its balance sheet remains unsteady.

Victory in the last elections tightened the Badals’ grip on party and state, but Sukhbir Badal, as the nextgen leader, has his task cut out. He talks development, but the party is yet to internalise it. He campaigned in 2012 on the platform of development, good governance and welfare, but a senior journalist, who has covered Punjab politics for many years, says that behind the scenes he used the usual tactics: Encouraging rebel candidates in key constituencies, sewing up alliances with community leaders, distributing seats to Hindus and wooing potential rivals with key positions. “They are inclusive in a patriarchal way. They cannot tolerate dissent,” says JNU’s Jodhka. “Sukhbir Badal is a feudal [sic] who has come to town. It remains to be seen how the feudal [sic] establishes himself in town. You have to have a democratic sensibility.” If Sukhbir Badal manages to inculcate that sensibility in himself, his party and the state, he can emerge as Punjab’s changemaker.

First Published: Jan 15, 2013, 06:31

Subscribe Now