On September 7 this year, 29 Hero MotoCorp executives—all members of the top management team, including a few handpicked future leaders—were at Harvard University on a five-day immersion programme. The course focussed on two areas: How the mobility space will shape up in the future and, in that context, how they should revisit their present business. The team also met a variety of stakeholders deeply involved in new tech—the Internet of Things, self-driving cars, for instance—and visited world-class laboratories and incubators in and around Boston.

Though the company has previously undertaken scenario planning—that is, infusing flexibility in long-term plans—this was the first time that such an elaborate exercise was attempted. The reason, Pawan Munjal, chairman, managing director (MD) and CEO of Hero MotoCorp, tells Forbes India, is quite simply to not be taken by surprise in the future.

“Hero MotoCorp is a mobility company and it [mobility] is one of the top three disrupted sectors in the world today,” he says during a two-hour-long interview in early September. “We need to be very mindful and aware of what is going on in that space—which way the world is moving and the kind of things that are happening—to stay ahead of the curve.” We met the industrialist at his South Delhi Panchsheel residence, heavily populated with paintings, sculptures and figurines that cut across multiple cultures.

During the course of the conversation, it became clear that the 61-year-old Munjal’s focus is the road ahead. And it is also evident that he is able to look forward because Hero MotoCorp’s present is secure and under control.

This stability is a far cry from five years ago when, on January 1, 2011, Hero and its Japanese partner Honda Motor Company parted ways after an extremely successful joint venture—Hero Honda—that lasted 26 long years. This association had transformed India into a motorcycle market, and, in the process, consigned geared scooters into the annals of history. With almost no product development capability post-separation and India’s two-wheeler market evolving rapidly, many had predicted the downfall of Hero MotoCorp (the name taken on by the company after the split). “People gave up on the company,” recalls Munjal. “But we have proved everyone wrong.”

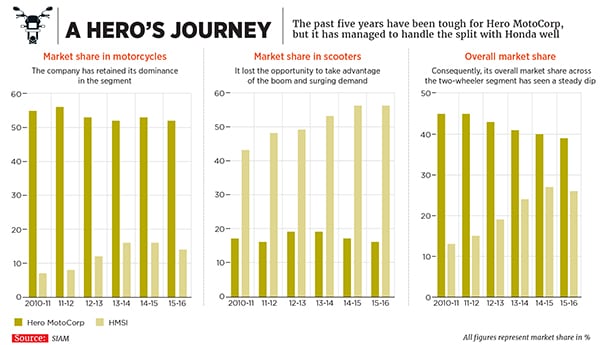

Having retained its dominant position in the motorcycle segment, Hero MotoCorp continues to be the largest two-wheeler player in the country with a 39 percent market share this is despite an onslaught in the scooter category by its erstwhile partner Honda through its wholly-owned subsidiary Honda Motorcycle and Scooter India (HMSI).

Hero MotoCorp sold 66.32 lakh units (including motorcycles and scooters) in FY16, posting sales worth Rs 28,990 crore it generated a profit of Rs 3,132 crore, 31 percent higher than the previous year. The markets acknowledged this performance, with the market capitalisation rising by 12 percent to Rs 58,823 crore. Meanwhile, the share price, which was Rs 1,986 on December 31, 2010, had touched Rs 3,500-levels as of mid-September this year.

The numbers aside, even more important is the fact that the company has managed to build critical product development capabilities in this period: One, by investing in the right people and, two, by establishing the Centre of Innovation and Technology (CIT) at Jaipur. Splendor iSmart 110, the first product developed end-to-end at CIT, hit the market in July this year and has been well received.

None of these successes, however, has bred complacency. After all, the company has motored through several highs and lows in its decades-long journey.

The partnership

When Hero Group and Honda Motor Company came together for a joint venture (JV) in 1984 to produce and sell motorcycles in India, not many expected them to achieve the success they did. After all, India was then a predominantly scooter market. But Hero Honda Motors, as the JV was christened, thanks to its fuel efficient and technologically superior bikes, changed the Indian market and soon grew to become not just the biggest player in the country but also the largest two-wheeler manufacturer in the world. “Hero and Honda were ideal partners. Hero had in-depth knowledge of the Indian market while Honda was a technology leader. Both learnt a lot from each other and worked together effectively by complementing their skills,” says Raamdeo Agrawal, co-founder and MD, Motilal Oswal Financial Services, whose investment in the company and the returns he made is legendary, but more on that later.

The problem started when the learning stopped. By the turn of the century, Hero Honda was a force in the Indian automotive space. “As a market leader, we were expected to lead the industry in every forum but the reality was that we had no engineering capability. It hurt [us] badly,” says Munjal. “As per the joint venture agreement, Honda developed the products and gave us the drawings which we used to produce the bike. We were not allowed to make any modifications.” But Honda’s research and development (R&D) facility in Japan catered to over 40 markets worldwide and the lead time to develop a product for India was frustratingly long—three to four years, typically. For instance, Karizma, its premium bike, took 42 months. Even variants with minimum changes took nine to 12 months.

Soon other irritants emerged.

Around 2005, the global markets opened up and competitors like Bajaj Auto began to export in large numbers. The JV agreement restricted Hero Honda’s exports to just four markets—Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh and Colombia. “We asked Honda to allow us to export to more markets but our request was turned down,” says Ravi Sud, senior vice president and CFO, who joined the company in 1998 when its volumes were just 4 lakh units. In the meantime, the royalty payout began to increase substantially as volumes rose and so did the product range. “It amounted to as much as 3.68 percent of sales or Rs 500 crore a year in 2010,” says Sud.

What further complicated the relationship was HMSI. Honda started its subsidiary in 1999 after taking a no-objection certificate (NoC) from Hero Group. The agreement entailed that, for a period of five years, HMSI would not launch motorcycles and Hero Honda would not enter the scooter segment. “Many people asked us why we gave the NoC. But we had little choice. We were completely dependent on them for technology,” says Sud. At the end of the five-year period, HMSI began to launch motorcycles—first 150 cc, then 125 cc and lower. That did not go down well with Hero Honda as they did not have access to the R&D to launch scooters immediately. The JV’s first scooter, Pleasure, only came out in 2006 but by then, HMSI had taken leadership in that segment.

The separation

Not surprisingly, Hero Group’s cup of frustration overflowed. Towards the end of 2010, it approached its partner with a proposition: Rework the JV agreement to include transfer of technology and a global play for Hero Honda or part ways amicably. But Honda’s HMSI had by then built up a 50 percent market share in the scooter segment and the Japanese partner chose the second option. On December 16, 2010, the board of Hero Honda took the call and the Hero Group agreed to buy out Honda’s 26 percent stake in the JV the split came into effect from January 1, 2011.

“As a country, the government promotes JVs hoping that technology will come in and so will product development capabilities. But, in reality, you are left high and dry. Either the Indian partner sells out or remains a junior partner,” says Munjal. “We wanted to succeed and build a strong Indian brand.”

On August 9, 2011—within nine months of the separation—brand Hero MotoCorp was launched in London and music director AR Rahman’s theme song ‘Hum Mein Hai Hero’ (There is a hero within us) began to flood the airwaves. “We had time till June 2014 to use the Hero Honda brand but we chose to move on,” says Munjal. “It was not easy to give up the brand as it had become a household name in the country.”

The branding blitzkrieg that followed helped the company keep up the sales of its existing products. But challenges inevitably emerged. “In the last five years, the Indian two-wheeler market changed radically,” points out Malo Le Masson, head–global product strategy at Hero MotoCorp. The major change he refers to is the rapid acceleration in demand for gearless scooters. Between 2010-11 and 2015-16, the volume of scooters sold rose from 90,000 units to 6 lakh units. The scooter’s overall share in the two-wheeler segment shot up from just 10 percent to 30 percent. Hero MotoCorp launched Maestro (which was under development at Honda R&D at the time of the separation), its second scooter offering after Pleasure, but that failed to make an impact. The company’s market share in the scooter segment remained flat at 16 percent in this period. Around the same time, the demand for premium bikes (150 cc and above costing over Rs 1 lakh) began to surge led by Bajaj’s Pulsar. Hero MotoCorp, which at one point had a 25 percent share in the premium bikes segment, had no product to offer.

“After the split we focussed on the commuter segment [100/110 cc] as we had to prioritise our resources,” says Masson. This hurt the company as its market share in the motorcycle segment declined from 55 percent in 2010-11 to 52 percent in 2015-16. It managed to hold its sway in the commuter motorbike segment with products such as Glamour registering a strong demand. However, a poor presence in the scooter (which saw significant growth in volumes) and premium bike segments saw Hero MotoCorp’s overall two-wheeler market share decline from 45 percent in 2010-11 to 39 percent in 2015-16. HMSI in the same period doubled its overall market share from 13 percent to 26 percent.

Despite the dip, Hero MotoCorp managed to retain its leadership. “It is amazing how Hero MotoCorp even managed to remain a dominant player after the JV ended. Though it was unable to develop new products, it managed to bring in periodic variants to keep the commuter motorcycle product portfolio fresh,” says Markus Braunsperger, chief technical officer (CTO) of the company.

Building R&D capability

Munjal realised early that he had to build product development capability at Hero MotoCorp in a calibrated manner. As a first step, he identified the partners they would work with. Hero MotoCorp tied up with AVL Austria for engine development. Italian company Engines Engineering was brought in for end-to-end product development. US company Erik Buell Racing was roped in to upgrade existing products and also develop high-end bikes—250 cc and above (this company declared bankruptcy in 2015 and has since shut down). Initially, the partners helped the company launch minor refreshes and slowly the work deepened to include major upgrades.

“To do bigger projects, even with external partners, you need a certain product development capability within the company. After all, we need to give the right direction to the partners,” says Braunsperger. He was one of the first hires that Munjal made towards building the company’s R&D capacity. A 25-year BMW veteran, he took up the offer for the challenge it posed. “BMW just completed 100 years of operation. But here at Hero MotoCorp the challenge is very different—how to create a company’s product development capability from scratch,” he says.

The company’s R&D strength when the JV split was 170 people who spent most of their time coordinating with Honda R&D. “When I came on board, the R&D function was a Honda legacy and was not suitable to build in-house capability,” says Braunsperger. He began hunting for talent all over the world. For instance, Masson, a former Nissan executive, was brought in to chart the global product strategy. Today, expats from about 10 countries work on various aspects of product development. “We are creating a truly global organisation,” says Munjal proudly.

Next on Braunsperger’s agenda was setting up dedicated infrastructure for product development. Thus far, whatever little expertise that rested within Hero MotoCorp had been scattered across various manufacturing facilities. CIT began to take shape and was officially unveiled in March this year. “Costing Rs 850 crore, CIT houses new product design, prototype manufacturing, testing and validation facilities,” says Braunsperger who heads the facility. It also has a 16-km test track with 42 different surfaces that simulate road conditions in different parts of the world.

“At CIT, we do not have a pool of people, each with 25 years of experience. Experienced people tend to be stubborn. We have a whole lot of talented youngsters who are open to new approaches, think out of the box and are eager to learn,” he says. “We have seasoned experts to guide and offer leadership skills to the youngsters.” Munjal too is happy with the way CIT has shaped up. “In terms of hardware and infrastructure, we are set. We are building the team. We still have some way to go,” he says. “The amount of work that is being done is huge.”

Engineers at CIT are currently working on 30 new products apart from a wide range of new technologies, including electric bikes, power trains that run on alternate fuel, flexi-fuel and hybrid technology. “The challenge before us is to develop the right product, at the right cost, in a minimum lead time and deliver it in a manner that it can be mass produced at one bike every 17 seconds,” says Braunsperger. “Add to that product reliability that survives the five-year warranty Hero MotoCorp offers for all its bikes. Under Indian conditions, it is quite a promise.”

Proof of the pudding

In September 2015, Hero MotoCorp launched two new scooters—Maestro Edge and Duet. Both these products were developed in-house. They were the first significant launches in the last five years. “For us, this is the first step. The scooter segment will continue to grow and we will launch more products,” says Masson. This was quickly followed by the launch of Splendor iSmart 110 in July this year. This was the first product/bike to be entirely developed at CIT and features Hero MotoCorp’s patented i3S technology which switches off the engine when it is idle and turns it back on when the clutch is pressed. This helps improve fuel efficiency.

He also reveals that the company has a “very aggressive strategy” for the premium bike segment. “The new Achiever will be launched soon and we are also planning to launch the Xtreme200 Sport bike for those who like to race,” adds Masson.

These steps will push Hero MotoCorp in the right direction. Take this report from HSBC Research, which suggests that Hero MotoCorp needs to replicate what Maruti has achieved in the four-wheeler market. “Both Hero and Maruti have similar strengths. Both enjoy strong distribution reach and brand recall due to low cost of ownership and resale value. Both enjoy being a preferred choice of first-time buyers. However, with multiple strong product launches and the new NEXA distribution channel, Maruti has successfully moved into the premium segment which has significantly improved the long-term outlook for Maruti,” the report says. “Hero MotoCorp’s penetration in the premium market should eventually drive the long-term value of the stock. Currently, Hero has less than 2 percent of its volumes from the premium segment.”

![mg_88991_hero_motocrorp_280x210.jpg mg_88991_hero_motocrorp_280x210.jpg]()

And Hero MotoCorp is trying hard to make up for lost time. It plans to launch 15 new bikes between now and March 2017. “In the next 2-3 years, our portfolio would have changed significantly,” Masson adds. Among the new launches will be products that are specifically developed for export markets, one aspect of the business that has not gone as per the script for Hero MotoCorp.

Considering that restrictions on participating in the global play was one of the triggers for the JV split, Hero MotoCorp is yet to crack its international sales. Its exports in FY11 were 1.33 lakh units and 2.10 lakh units in FY16 (when, in comparison, Bajaj Auto exported 14.59 lakh units).

Global economic conditions are partly to blame. The company had set up two JVs in promising markets —Colombia and Bangladesh (where the manufacturing facility is under construction). But the Colombian peso depreciated by 60 percent pushing up the cost of production also, inflation in the country rose sharply as did interest rates. Its market for bikes shrunk from 700,000 units to 660,000 units in 2015 and is expected further fall to 600,000 units this year. Hero MotoCorp’s other big markets such as Nigeria and Argentina are also in deep crisis. “Most markets have crashed. Their recovery is unpredictable. We are, however, ready with products for these markets,” says Masson.

The other significant challenge looming large for the company is the shift to Bharat Stage VI emission norms in 2020. It has already entered into a JV with Fiat subsidiary Magneti Marelli for fuel injection technology. “Now that it has been mandated by the government, we have taken it up as a challenge. The industry would have ideally liked more time. The entire ecosystem has to change,” says Munjal. “Will the government be ready with the fuel?”

Top gear for tomorrow

Munjal, on his part, is ensuring Hero MotoCorp is future ready. He has handpicked Rajat Bhargava—who was senior partner, heading the industrial practice in India, at McKinsey’s—as head of strategy and performance transformation. The role, says Bhargava, means “I have to ensure that the company is not surprised by any development. We should surprise others and that is real victory.” His strategy is bi-focal: To study how changes impact existing business and how the company can take advantage of the disruption and prepare for the future.

To that end, Bhargava also wants the organisation to absorb certain beliefs. For instance, only those who cause change will lead, to cause that change you need to innovate and, while Hero MotoCorp may not be able to act or be as nimble as a startup, it can think like one and one idea isn’t enough to set you up for life. In essence, “we want to combine the experience and strength of Hero MotoCorp with the nimbleness and passion of a startup,” Bhargava says. It helps that they have begun to engage with startups too. Munjal, in his personal capacity, has already invested in Bengaluru-based two-wheeler taxi startup Rapido. “We are open to investing in startups, says Munjal. “We are opening two of the 11 floors at CIT for innovation not necessarily linked to mobility.” The most pragmatic way to innovate, he points out, is to tap external innovation. So the company has held idea contests and is working with incubators and startups. “We have already got some ideas. They are not about any new technology but new solutions. We will deploy them in the next six to 12 months,” says Bhargava.

These concerted efforts to prepare for what’s next are what make Hero MotoCorp an investor favourite. Let’s circle back to Motilal Oswal’s Agrawal who bought five lakh shares in Hero Honda at Rs 30 in 1995-96 and held on to them even after the JV broke up and pessimism held sway. “Hero MotoCorp has a committed management. Also, it has always been a zero-debt company which has mastered the art of working on negative capital employed. When business makes money without deploying capital, the valuations typically go through the roof,” he says.

His faith was validated. Agrawal sold his shares (for corporate governance reasons as his firm had started a mutual fund) in 2015 at Rs 2,600 per share. He regrets not being able to hold on to the stock. And that is a hat-tip to the future Hero MotoCorp is promising.