It has been another year of horrible headlines for Mexico. Three hurricanes wracked the country, killing hundreds and causing billions in damage. The drug war continues, with more than 60,000 killed since 2006. And after rebounding from the 2008 crash, and even luring away manufacturing jobs from China, Mexico has seen its annual economic growth rate sag to less than 1.5 percent.

Yet there is reason for hope. In the shadow of all this hardship a radical transformation of Mexico’s economy is on the horizon. Under the leadership of new President Enrique Peña Nieto, the country’s congress will by the end of this year almost certainly pass a constitutional amendment to open up its oil and natural gas sector to private investment. By this time in 2014 the likes of ExxonMobil, PetroChina and Norway’s Statoil could even have contracts in place to start exploring for Mexico’s untapped oil and gas bounty.

“The opportunity to accelerate our economy is inside of our country—it’s in the decisions that we will make as a nation,” said Peña Nieto in a recent speech.

Emilio Lozoya, chief executive of state oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (known as Pemex), agrees with his boss. “We are very confident that in the very short term an energy bill will be approved,” he says. “More than a dream come true, it is something that is long overdue.”

How big could Peña Nieto’s oil reforms be for Mexico’s economy? Not only will it be bigger than the revolution in shale drilling and fracking has been in the US, says Duncan Wood, director of the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center: “This will be the most significant change in Mexico’s economic policy in 100 years.”

Despite massive reserves, Mexico has one of the world’s most notoriously closed-off oil industries. The Mexican constitution makes it illegal for anyone but Pemex to even own a barrel of oil. If you’re a farmer in Mexico and oil is discovered underneath your land, not one drop of the black gold is yours—it belongs to the state, to the people. There are no private companies operating oilfields in Mexico, no risk-based production sharing contracts or joint ventures with any international oil companies.

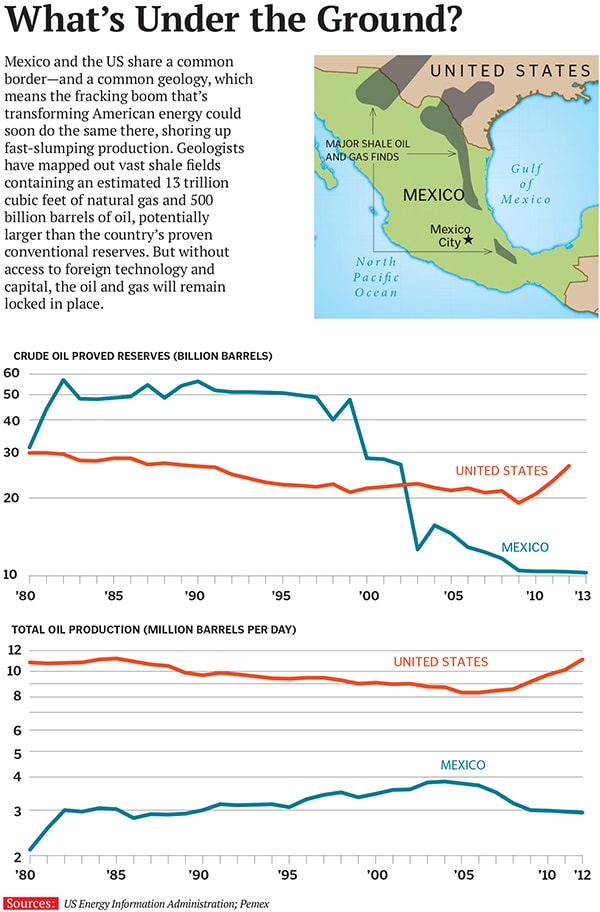

Without reforms, much of Mexico’s estimated 30 billion barrels of oil and 500 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (about the same as Brazil) will simply remain locked in the ground. Pemex, despite being one of the world’s biggest oil companies, does not have sufficient technical expertise to explore and develop promising prospects in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico or in the tricky shale layers just south of the border from Texas’s booming Eagle Ford fields. What’s more, Pemex has virtually no hope of acquiring or borrowing such expertise under the status quo, which allows the company to enter into only service contracts.

Big Oil companies like ExxonMobil or Chevron won’t even consider taking on the massive risks of drilling complex wells without a guaranteed cut of whatever oil and gas they find. And with Mexico relying on Pemex revenues to fund a third of the federal budget, Pemex is chronically starved of the capital it needs to develop the expertise to do it itself.

No wonder Lozoya is excited for change. “You will have industrialisation in Mexico that didn’t exist before,” he said recently. “After all, we share the same geology as the USA.”

In 1938 President Lázaro Cárdenas, in response to rampant profiteering by American oil companies, nationalised the sector. Resource nationalism worked all right for Mexico through most of the past 75 years—especially through the 1980s and 1990s as Pemex developed the supergiant Cantarell field in the Gulf of Mexico. Discovered in 1972, the Cantarell field was one of the world’s biggest, with production volumes peaking at 2.2 million barrels per day in 2003.

That year also marked Mexico’s oil peak at 3.4 million barrels per day. Cantarell has since plunged to 450,000 barrels per day. Pemex has sought to replace Cantarell’s barrels, but new developments have been smaller, trickier and far more expensive to develop. Pemex’s total daily production has fallen to 2.5 million barrels.

![mg_72749_mexico_oil_280x210.jpg mg_72749_mexico_oil_280x210.jpg]()

This has left a smaller cut for the cash-starved government. In 2005 oil and gas revenue accounted for 41 percent of government revenue. That fell to about 30 percent last year as Pemex had to fork over $69 billion out of its $127 billion in revenues to the government. Feeding the bureaucratic maw has left Pemex woefully starved of the capital it needs to reinvest and grow. Its balance sheet is weighed down with $52 billion in long-term debt net of cash (in contrast, ExxonMobil and Chevron have no net debt). Lozoya would like to boost capital spending 50 percent to $37 billion a year, but that would (in the short term) reduce the government’s take, requiring budget cuts or new taxes.

A generation of politicians recognised that something had to change. Presidents Carlos Salinas, Vicente Fox and Felipe Calderón all expressed a desire to open up Pemex but never got far. Calderón managed to push through something called the “integrated service contract” whereby Pemex has been able to bring in foreign oil companies like Halliburton to provide drilling services. But that’s clearly not enough.

“Mexicans started to believe that there was a problem,” says Wood. So the question soon became “What is the right way forward?”

Enrique Peña Nieto’s ascent to become Mexico’s most powerful man was part of a meticulously planned career. The oldest of four siblings born to an electrical engineer and a schoolteacher just outside of Mexico City, Peña Nieto was a bad student who sat in the back of the class to play chess with a friend, covering the board with a book to trick his teachers.

Armed with a law degree, an MBA and his good looks, he began his career in politics working for his uncle, Arturo Montiel, who was governor of Mexico state, the country’s largest. Peña Nieto became governor in 2005, using every opportunity to showcase his successes.

A turbulent personal life almost proved his undoing. First Peña Nieto was rocked by revelations that he sired a child out of wedlock. Then in 2007 his wife died suddenly after a seizure induced a heart arrhythmia. In 2010 he married telenovela star Angélica Rivera in a wedding that was on the cover of every tabloid magazine in Mexico.

But as governor Peña Nieto proved himself a pragmatist, forging alliances and delivering crowd-pleasing infrastructure projects. He emerged as the great hope of the PRI, the Institutional Revolutionary Party, which ruled Mexico for seven straight decades until being unseated in 2000. After two presidents from the right-leaning PAN (National Action Party) failed to revitalise the country, angry, exhausted voters were ready to give the PRI another shot. Peña Nieto ran for president on promises of ending the drug wars and revitalising the economy and won a narrow victory in 2012 with just 38 percent of the popular vote.

Within days of taking office Peña Nieto put his pragmatism on display, bringing together leaders of the PRI, PAN, leftist PRD (Revolutionary Democracy Party) and Green Party to forge the “Pacto Por Mexico”—a political compact enshrining a blueprint for reforms. In a whirlwind year the congress has tackled reforms to fix the public school system, to bring more competition to the telecom sector and to improve tax collection, among other things.

Some proposals, like a fat tax on sugary drinks, have faced resistance.Teachers have staged massive street protests against education reforms. But all told, Peña Nieto’s consensus-building leadership has made a mockery of what passes for governance in Washington, DC. “We ran on a platform about reforms,” says Lozoya, who was part of the president’s transition team. “And we have passed in the past 10 months more reforms than in many, many years before added together.” Yet, despite the hunger for change, the Mexican public remains deeply wary about privatisation, and it’s easy to see why. Deregulation of the telecom industry there led to the rise of Telmex, which created the fortune of Carlos Slim Helú—the richest man in the world. The fact that he made his fortune off the privatisation of a monopoly is anathema in a country where so many millions still live in poverty.

![mg_72751_mexican_revolutionary_280x210.jpg mg_72751_mexican_revolutionary_280x210.jpg]()

Sixty percent of the people are against allowing foreign companies to invest in Pemex, says Daniel Yanes, director at pollster Buendía & Laredo in Mexico City. “If they brought it to a [popular] vote they would lose,” he says of Peña Nieto’s plans.

No wonder in his speech introducing his oil reforms, Peña Nieto summoned the ghost of Cárdenas and put a different spin on his legacy. Though lionised as the president who changed the constitution to nationalise Mexico’s oil industry, Cárdenas had, in his final days in office in 1940, modified the laws in order to allow Pemex to enter into production-sharing and profit-sharing contracts with private, Mexican-owned companies. Cárdenas’ successor, Manuel Ávila Camacho, took it a step further and created a secondary law enabling Pemex to enter into such partnerships with foreign-owned oil companies, as long as Pemex controlled a majority of the venture.

What few remember now is that this sensible production-sharing arrangement endured until 1959 when President Adolfo López Mateos modified those laws again. López Mateos killed the upside potential for Pemex’s private partners and eliminated their incentive to take risks by requiring that Pemex pay them not “in kind”—with a set percentage of extracted oil—but in cash.

So Peña Nieto proposes to cancel the restrictions put on Pemex by López Mateos and to return Mexico’s oil laws “back to the way it should be”—without provoking a popular backlash. His proposed amendments say all oil and gas in place belong to the state and Mexico is not going to grant “concessions” that confer any right of ownership. He also proposes that Mexico’s congress set policies dictating the development of those resources.

These changes are designed to be as simple as possible to garner the required two-thirds vote in Congress for constitutional amendments. “In essence all Peña Nieto asks is a clean slate at the constitutional level upon which the politicians will then apply the details of policy,” says Jose Valera, an attorney at Mayer Brown in Houston. The “secondary legislation”, as it’s called, requires just a simple majority to pass and will be the real guts of the changes to the Mexican oil patch.

The end result won’t be anywhere near as liberal as in the US, of course, where property owners have rights to the minerals under their land. But it will move Mexico more in the direction of Brazil and Norway, which have big state-sponsored oil companies in Petrobras and Statoil, and also welcome foreign capital to invest in exploring and developing their oilfelds.

Peña Nieto will have to negotiate with Mexico’s other political groups to get anywhere. Mexico’s major leftist party, the PRD, is in favour of Pemex keeping more of the cash it generates but against any foreign involvement.

“The energy reform presents a grave danger for Mexico,” declared leftist firebrand Andrés Manuel López Obrador, in a recent speech. “The masses don’t know that they are going to take the energy sector, which is akin to bleeding Mexico to death, leaving us empty-handed.” He has mobilised street protests against the oil reform. Still, the PRI and the PAN party, along with some PRD allies, should be able to muscle through the amendments. “The PRI is looking for greater consensus, Peña Nieto is looking for greater consensus, but when they have to do it, they will,” says Gabriel Lozano, JPMorgan’s chief Mexico economist.

While Big Oil is interested, there’s good reason that BP, ExxonMobil, Chevron and Statoil all reply with a “no comment” when asked their opinion of Mexico’s reforms. “Anything that an international oil company would say positive about oil reforms would be used by the opposition to undermine them,” says one company insider.

A potential sticking point: Even after the reforms are passed, Mexico’s constitution will still declare that only the state may claim ownership of oil and gas in the ground. So the big question is how to enable private oil companies entering into risk-based contracts with the government to book those same hydrocarbons on their balance sheets as reserves.

This matters, because if oil companies can’t claim the future value of those barrels, then they can’t use them as collateral to raise the cash they need to drill them up and get them to market. “The question is, can a solution be found where supermajors don’t take possession of the oil so they don’t violate the Mexican constitution but get a call on the utilisation of reserves?” says Neil Brown, the former top Republican staffer on international energy policy. “The Exxons and Chevrons won’t be able to take ownership of physical oil what they need to have is a call on that oil to be disposed or sold.”

Peña Nieto’s administration has been talking with oil companies and with the Securities & Exchange Commission and has proposed allowing international companies to record their economic interest in risk-sharing contracts in such a way that under SEC rules they can book reserves even though the state will technically retain full ownership of the oil.

So what will happen to Pemex? Though top executives at Pemex—including 39-year-old CEO Lozoya—are intimately involved in the process of taking the shackles off, not even they expect Pemex to be the only game in town when it comes to developing Mexico’s oil and gas. Rather, the plan is to create a new ministry that will oversee Pemex and auction off exploration blocks to private operators. “We hope large international players will come and join forces with Pemex or directly with the government if they decide so, both on the service and the operational side,” says Lozoya. “This will strengthen Pemex significantly. We are strong believers that competition will make us much more transparent and more efficient.”

The entry of other companies to work with and even compete against Pemex would invigorate the sector. Pemex doesn’t have sufficient technical capacity to go after oil in the ultradeep Gulf waters, for instance. What’s more, the company is dragged down by bloated staffing. As a result Pemex has among the lowest rates of productivity—measured in barrels of oil per worker—of any company in the world. Pension liabilities are an enormous $100 billion. “Pemex needs a tremendous restructuring. We need to change the culture of the company,” says Lozoya. “People are not paid for results here.”

Understanding the power of the Pemex workers union to throw sand in the gears of reform, Peña Nieto has been careful not to run afoul of workers. Instead of pursuing corruption charges against powerful union boss Carlos Romero Deschamps, the PRI made him a senator.

Lozoya says the goal is for Pemex to grow so fast that he can create plenty of new work to keep his bloated staff busy. Meanwhile, Mexico’s entrepreneurs, including Carlos Slim, have formed drilling companies to work under contract for Pemex.

The hottest spot has been in the offshore drilling business. Nowhere in the world are jack-up rigs for use in coastal waters in such high demand shallow water drilling remains a core competency for Pemex. The leader among Mexico’s indigenous offshore drillers appears to be Grupo R (controlled by Ramiro Garza Cantú), which has what’s thought to be the biggest fleet of shallow-water drilling rigs in Mexican waters and has five new rigs on order at a cost of roughly $1 billion. Guillermo Vogel Hinojosa, vice chairman of Tenaris-Tamsa, has positioned himself as Mexico’s primary steel pipe manufacturer.

As for Slim, his Grupo Carso provides substantial drilling services to Pemex and earlier this year inked a $415 million, seven-year contract to lease a drilling platform to Pemex. In 2011 Carso acquired 70 percent of Tabasco Oil, which drills in Colombia and also owns an 8 percent stake in Argentina’s state-controlled oil company, YPF.

As former President Calderón explained in a September speech, there have been thousands of wells drilled into the Eagle Ford shale field in south Texas but only a few dozen on the Mexico side. The low-hanging fruit is just waiting there. “The oil does not respect the borders,” he said.

Calderón and his predecessors may have pushed for real oil reforms, but it’s Peña Nieto who will get the spot in the history books. “Everyone had realised the problem, but nobody wanted to tackle the challenge of constitutional reform,” says Steven Otillar, attorney with Akin Gump in Houston. “Rather than ‘Oh my gosh, how fast this is going,’ it’s more like ‘Thank God we’re finally there.’”