The soul of Africa in Brazil

Rio may be one of its most exciting cities, but it is in Salvador that many of Brazil's cultural roots lie and where the spirit of another continent still thrives

A man dances at an Umbanda terreiro, or temple. Candomblé and Umbanda are syncretic religions, most visible in Salvador, that fuse African traditions with Catholicism. They emerged as a reaction to the forced conversions of African slaves to Christianity (Image: Sachin Bhandary)

“Concentrado irmao,” Mario almost yelled, instructing me to concentrate. Despite the smile on his face, I could see he was getting a little impatient. Understandably so—I wasn’t being a good student.

I was in Salvador and it had been a week since he had started teaching me drums in a garage in Curuzu, a slum or favela as it is known in Brazil. However, I hadn’t managed to master even the basic rhythm. It wasn’t unexpected though, considering it was the first time I was trying my hand at playing any musical instrument. You may wonder: Why was I doing this now?

Well, most people equate Brazil with Rio de Janeiro, its beaches, favelas and its colourful Carnival. While it is true that Rio is one of the most exciting cities on the planet, even it cannot truly represent the massive melting pot that is Brazil. The fifth largest country in the world is also an astonishing amalgam of race and religion and many of Brazil’s most iconic symbols, from samba, batucada (a variant of the samba) and capoeira (a martial art form) to the Brazilian staple dish of feijoada, go back to its African heritage.

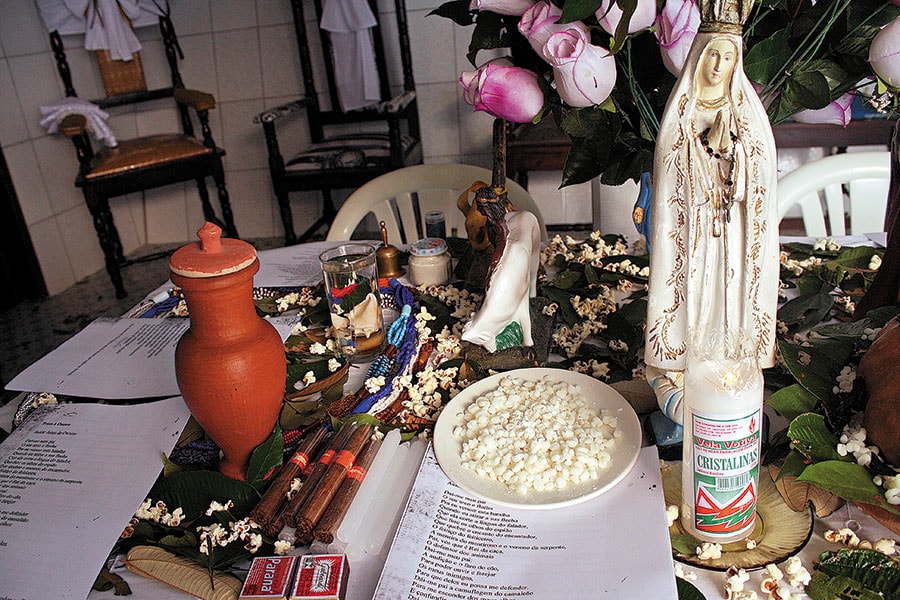

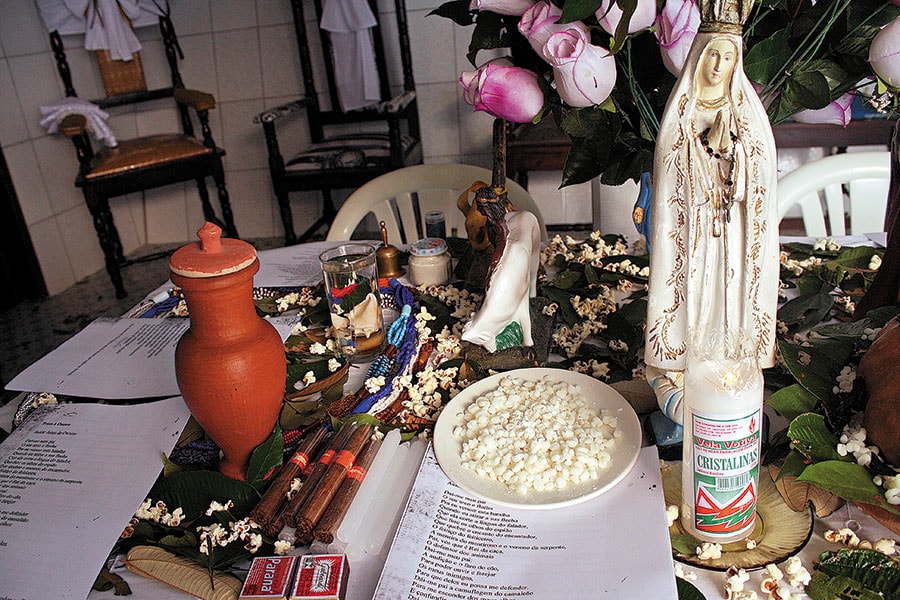

Brazil has the largest population of people of African descent outside of Africa, and Salvador (historically, a port of entry for people being brought in from Africa to work as slaves in the sugarcane estates across Brazil) is where many of the Afro-Brazilian roots lie. It is also where Candomblé, the syncretic religion that combines Catholic Christianity and pan-African faiths, was born. And what better way, I thought, to scratch the surface of Salvador than to learn to play drums the way they do in a Candomblé terreiro (temple)? An Umbanda terreiro, where Christian gods and African rituals share space (Image: Sachin Bhandary)

An Umbanda terreiro, where Christian gods and African rituals share space (Image: Sachin Bhandary)

I had enthusiastically set myself that challenge but the task turned out to be more difficult than anticipated. To begin with, because there is no formal process to learn Candomblé music, it is difficult to find a teacher.

I fortuitously ran into Mario Pam, the head drummer of an Afro-Brasilian music group called Ile Aye, who decided to take me under his wing. Mario’s group Ile Aiye is among the most famous in Salvador, and holds pride of place in the city’s carnival. Despite his busy schedule, Mario agreed to teach me Candomblé rhythms and also promised to take me to the terreiro where he played regularly. So, every afternoon, I would take an ‘onibus’ (bus) from ACM (short for Antônio Carlos Magalhães), an affluent neighbourhood about 10 km from the old centre of the city, where I was put up for the month that I was supposed to be in Salvador, and make my way to Curuzu, close to the northern part of the city. And there, the heavily-built Mario would be waiting for me, almost always smoking a cigarette.  A scene from a Candomblé ceremony (Image: Mario Tama / Getty Images)

A scene from a Candomblé ceremony (Image: Mario Tama / Getty Images)

Despite being a predominantly Catholic country and sometimes aggressively so, many other religions have survived and flourished in Brazil. Among them are Candomblé and Umbanda, which emerged as a reaction to the forced conversions of slaves to Christianity. “Catholic get-togethers organised by slaves became platforms where they rediscovered their shared ancestry, giving birth to Candomblé,” Mario tells me. While Candomblé is an amalgam of multiple African ethnic faiths and includes worship of several ancestral deities, Umbanda, a spiritualistic doctrine founded by a French educator named Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail in the 1840s, includes a few more elements from Spiritism. “But more than the religions, it is a story of a people struggling to keep their collective heritage alive,” Mario says.

There are many misconceptions surrounding both these religions. Some accuse them of practising witchcraft, others of being pagan and a few others equate it with devil worship. “The new threat comes from the rise of Evangelicalism. Brazil continues to be the largest Catholic country in the world, but Evangelicalism has grown at a staggering pace in the last two decades. And the fundamentalists amongst Evangelicals are calling for a ban on abortion, are not in favour of increased LGBT rights and encourage prejudice against the Afro-Brasilian religions. A few times, Candomblé and Umbanda terreiros have been attacked as well,” says Eliana Laurentino, a history professor based in Rio de Janeiro. In a way, through their existence, these faiths have had to fight for survival. The Yemanja goddess, one of the Candomblé orixas, worshipped as the queen of the salty waters (Image: Sachin Bhandary)

The Yemanja goddess, one of the Candomblé orixas, worshipped as the queen of the salty waters (Image: Sachin Bhandary)

I learnt that at the heart of Candomblé lies orixas, or lesser gods that serve the god of gods Oludumaré. There are several orixas and they differ depending on the Candomblé community. And the most celebrated orixa in this coastal city is Yemanja, as she is the queen of the salty waters. Every year, on February 2, Baianos (people from the state of Bahia of which Salvador is the capital) pay their respects both to Nossa Senhora Dos Navegantes (Our Lady of the Seafaring) and Yemanja by presenting gifts to her in the form of flowers and perfumes. Fishermen then take these gifts out to the sea. It is said that the ones washed back ashore are those that Yemanja has rejected.

There were many other lessons to be learnt in the quest to understand the drums. For instance, throughout the year, a festa, or party, is organised once or twice a month in the local terreiro. Preparation for these ceremonies begins days in advance and on the actual day the festa goes on from early evening to midnight and beyond. There is music and food, and sometimes cigars and alcohol too if the orixa is said to prefer it. Priests of the community are said to get possessed by the spirits of orixas and communicate with the audience. The festas are not limited to the praise of African orixas they sometimes also venerate those of indigenous Brazilian ancestors known as cubuclus. I was told the atmosphere at these parties can get charged and the orixas may instruct members of the audience to dance along—and they are obliged to do so.

Beyond religious objectives, these parties also serve as an opportunity for the community to mingle and enjoy some typical Bahian delicacies. Dishes you would find at most festas are caruru, made with okra, onions and shrimps, or vatapa, a creamy paste of ground peanuts, coconut milk, palm oil and dried shrimps, commonly eaten with rice, and feijoada, made with black beans, beef and pork.

The more I learnt about the drums and festas, the stronger I felt that my journey in Salvador would be incomplete without testing my drumming skills at these intense ceremonies. I had been working with Mario for four weeks now and had managed to make some progress. But despite his best efforts, he couldn’t get me permission to play at his terreiro. Just when I felt it was going to be an impossible dream, I got lucky again.

A friend of a friend came to my rescue and I was introduced to Pai (or Father) Washington, the leader of an Umbanda terreiro in another favela called Arenoso, considered one of the most dangerous areas in the city. But since Pai’s brother Bira, the in-house musician, agreed to help me with the drums and also let me play alongside him at a festa, I decided to brave it.  Drummer Bira, the in-house musician of an Umbanda terreiro. Festas, or parties, organised in local terreiros feature lots of food and music (Image: Sachin Bhandary)

Drummer Bira, the in-house musician of an Umbanda terreiro. Festas, or parties, organised in local terreiros feature lots of food and music (Image: Sachin Bhandary)

Bira was a tougher taskmaster than Mario. ‘Ser consistente amigo (With consistency, my friend)’, he would reiterate, frustrated at my inability to hold a rhythm. But it was a different terreiro, hence a new style, and I was starting from scratch. Again, I ploughed on, and at the same time got a glimpse into an Umbanda terreiro. Was it true they practised witchcraft? What about animal sacrifice? As the days went by, some of these questions were answered.

Despite the fact that they share common origins and even orixas, Candomblé and Umbanda differ a fair bit in ideology and practice. From what I observed, Candomblé tends to be more conservative and orthodox. Umbanda, on the other hand, could also include elements of witchcraft, depending on the terreiro. As for the music, that can vary too, and most practitioners of these religions will be able to spot the difference between the two rhythms.

The dissimilarity is evident even in the festas. The ones at Candomblé are quite focussed on African rituals, while the Umbanda terreiro I visited prayed regularly to its Christian gods and saints as well. And while Candomblé festas at most times appeared to be more serious religious affairs, those at Umbanda were more casual and inviting. They also had generous amounts of alcohol.

Every year, devotees present flowers and perfumes to the Candomblé goddess Yemanja and fishermen take these out to sea (Image: Cassiohabib / Shutterstock.com)But the best festa I attended obviously had to be the one I played at, in the Umbanda terreiro in Arenoso. By then, what was supposed to be a month-long stay had stretched to two. But despite over six weeks of training, my drumming skills did not match my expectations. Clearly, my love for music far exceeded my skill for it.

I was gripped with nervousness as I looked at the crowd. Of all the five festas I had attended in Salvador, this one had attracted the maximum audience. Word must have spread that an Indian was about to make a fool of himself!

When the moment arrived, I wasn’t able to produce even the most practised rhythm. The noise, the crowd and manifested orixas were pressures I was not prepared to deal with. It was only when Bira, my teacher, started playing alongside me that I was slowly able to get the rhythm. And that is because he started counting the beats loudly. ‘Ser consistente, amigo,’ he yelled again.

Immediately after, I took to the bass drums and I was able to play far better because the beats were a tad easier. That is when it sunk in: I was playing drums in a festa, far, far away from my country.

In about fifteen minutes, my role in the festa and at the terreiro was over. ‘Voltar, nos te amo (Come back, we love you),’ whispered Pai. Everyone at the terreiro in Arenoso hugged me, the way only Baianos can do.

Mario would often tell me, “Be it samba, bossa nova or musica popular from Brazil, most of them are influenced by the music in the terreiros of Salvador. Like these religions, Brazil’s culture is an amalgam.” I did notice Candomblé everywhere as I made my way through Brazil, but Salvador is the only city that carries the energy of Candomblé in daily life. Candomblé and Umbanda demonstrate the infallibility of the human spirit. And Salvador is where the soul of another continent still thrives, despite it being the place where it was meant to die.  An Umbanda terreiro, where Christian gods and African rituals share space (Image: Sachin Bhandary)

An Umbanda terreiro, where Christian gods and African rituals share space (Image: Sachin Bhandary)

I had enthusiastically set myself that challenge but the task turned out to be more difficult than anticipated. To begin with, because there is no formal process to learn Candomblé music, it is difficult to find a teacher.

I fortuitously ran into Mario Pam, the head drummer of an Afro-Brasilian music group called Ile Aye, who decided to take me under his wing. Mario’s group Ile Aiye is among the most famous in Salvador, and holds pride of place in the city’s carnival. Despite his busy schedule, Mario agreed to teach me Candomblé rhythms and also promised to take me to the terreiro where he played regularly. So, every afternoon, I would take an ‘onibus’ (bus) from ACM (short for Antônio Carlos Magalhães), an affluent neighbourhood about 10 km from the old centre of the city, where I was put up for the month that I was supposed to be in Salvador, and make my way to Curuzu, close to the northern part of the city. And there, the heavily-built Mario would be waiting for me, almost always smoking a cigarette.  A scene from a Candomblé ceremony (Image: Mario Tama / Getty Images)

A scene from a Candomblé ceremony (Image: Mario Tama / Getty Images)

Despite being a predominantly Catholic country and sometimes aggressively so, many other religions have survived and flourished in Brazil. Among them are Candomblé and Umbanda, which emerged as a reaction to the forced conversions of slaves to Christianity. “Catholic get-togethers organised by slaves became platforms where they rediscovered their shared ancestry, giving birth to Candomblé,” Mario tells me. While Candomblé is an amalgam of multiple African ethnic faiths and includes worship of several ancestral deities, Umbanda, a spiritualistic doctrine founded by a French educator named Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail in the 1840s, includes a few more elements from Spiritism. “But more than the religions, it is a story of a people struggling to keep their collective heritage alive,” Mario says.

There are many misconceptions surrounding both these religions. Some accuse them of practising witchcraft, others of being pagan and a few others equate it with devil worship. “The new threat comes from the rise of Evangelicalism. Brazil continues to be the largest Catholic country in the world, but Evangelicalism has grown at a staggering pace in the last two decades. And the fundamentalists amongst Evangelicals are calling for a ban on abortion, are not in favour of increased LGBT rights and encourage prejudice against the Afro-Brasilian religions. A few times, Candomblé and Umbanda terreiros have been attacked as well,” says Eliana Laurentino, a history professor based in Rio de Janeiro. In a way, through their existence, these faiths have had to fight for survival. The Yemanja goddess, one of the Candomblé orixas, worshipped as the queen of the salty waters (Image: Sachin Bhandary)

The Yemanja goddess, one of the Candomblé orixas, worshipped as the queen of the salty waters (Image: Sachin Bhandary)

I learnt that at the heart of Candomblé lies orixas, or lesser gods that serve the god of gods Oludumaré. There are several orixas and they differ depending on the Candomblé community. And the most celebrated orixa in this coastal city is Yemanja, as she is the queen of the salty waters. Every year, on February 2, Baianos (people from the state of Bahia of which Salvador is the capital) pay their respects both to Nossa Senhora Dos Navegantes (Our Lady of the Seafaring) and Yemanja by presenting gifts to her in the form of flowers and perfumes. Fishermen then take these gifts out to the sea. It is said that the ones washed back ashore are those that Yemanja has rejected.

There were many other lessons to be learnt in the quest to understand the drums. For instance, throughout the year, a festa, or party, is organised once or twice a month in the local terreiro. Preparation for these ceremonies begins days in advance and on the actual day the festa goes on from early evening to midnight and beyond. There is music and food, and sometimes cigars and alcohol too if the orixa is said to prefer it. Priests of the community are said to get possessed by the spirits of orixas and communicate with the audience. The festas are not limited to the praise of African orixas they sometimes also venerate those of indigenous Brazilian ancestors known as cubuclus. I was told the atmosphere at these parties can get charged and the orixas may instruct members of the audience to dance along—and they are obliged to do so.

Beyond religious objectives, these parties also serve as an opportunity for the community to mingle and enjoy some typical Bahian delicacies. Dishes you would find at most festas are caruru, made with okra, onions and shrimps, or vatapa, a creamy paste of ground peanuts, coconut milk, palm oil and dried shrimps, commonly eaten with rice, and feijoada, made with black beans, beef and pork.

The more I learnt about the drums and festas, the stronger I felt that my journey in Salvador would be incomplete without testing my drumming skills at these intense ceremonies. I had been working with Mario for four weeks now and had managed to make some progress. But despite his best efforts, he couldn’t get me permission to play at his terreiro. Just when I felt it was going to be an impossible dream, I got lucky again.

A friend of a friend came to my rescue and I was introduced to Pai (or Father) Washington, the leader of an Umbanda terreiro in another favela called Arenoso, considered one of the most dangerous areas in the city. But since Pai’s brother Bira, the in-house musician, agreed to help me with the drums and also let me play alongside him at a festa, I decided to brave it.  Drummer Bira, the in-house musician of an Umbanda terreiro. Festas, or parties, organised in local terreiros feature lots of food and music (Image: Sachin Bhandary)

Drummer Bira, the in-house musician of an Umbanda terreiro. Festas, or parties, organised in local terreiros feature lots of food and music (Image: Sachin Bhandary)

Bira was a tougher taskmaster than Mario. ‘Ser consistente amigo (With consistency, my friend)’, he would reiterate, frustrated at my inability to hold a rhythm. But it was a different terreiro, hence a new style, and I was starting from scratch. Again, I ploughed on, and at the same time got a glimpse into an Umbanda terreiro. Was it true they practised witchcraft? What about animal sacrifice? As the days went by, some of these questions were answered.

Despite the fact that they share common origins and even orixas, Candomblé and Umbanda differ a fair bit in ideology and practice. From what I observed, Candomblé tends to be more conservative and orthodox. Umbanda, on the other hand, could also include elements of witchcraft, depending on the terreiro. As for the music, that can vary too, and most practitioners of these religions will be able to spot the difference between the two rhythms.

The dissimilarity is evident even in the festas. The ones at Candomblé are quite focussed on African rituals, while the Umbanda terreiro I visited prayed regularly to its Christian gods and saints as well. And while Candomblé festas at most times appeared to be more serious religious affairs, those at Umbanda were more casual and inviting. They also had generous amounts of alcohol.

Every year, devotees present flowers and perfumes to the Candomblé goddess Yemanja and fishermen take these out to sea (Image: Cassiohabib / Shutterstock.com)But the best festa I attended obviously had to be the one I played at, in the Umbanda terreiro in Arenoso. By then, what was supposed to be a month-long stay had stretched to two. But despite over six weeks of training, my drumming skills did not match my expectations. Clearly, my love for music far exceeded my skill for it.

I was gripped with nervousness as I looked at the crowd. Of all the five festas I had attended in Salvador, this one had attracted the maximum audience. Word must have spread that an Indian was about to make a fool of himself!

When the moment arrived, I wasn’t able to produce even the most practised rhythm. The noise, the crowd and manifested orixas were pressures I was not prepared to deal with. It was only when Bira, my teacher, started playing alongside me that I was slowly able to get the rhythm. And that is because he started counting the beats loudly. ‘Ser consistente, amigo,’ he yelled again.

Immediately after, I took to the bass drums and I was able to play far better because the beats were a tad easier. That is when it sunk in: I was playing drums in a festa, far, far away from my country.

In about fifteen minutes, my role in the festa and at the terreiro was over. ‘Voltar, nos te amo (Come back, we love you),’ whispered Pai. Everyone at the terreiro in Arenoso hugged me, the way only Baianos can do.

Mario would often tell me, “Be it samba, bossa nova or musica popular from Brazil, most of them are influenced by the music in the terreiros of Salvador. Like these religions, Brazil’s culture is an amalgam.” I did notice Candomblé everywhere as I made my way through Brazil, but Salvador is the only city that carries the energy of Candomblé in daily life. Candomblé and Umbanda demonstrate the infallibility of the human spirit. And Salvador is where the soul of another continent still thrives, despite it being the place where it was meant to die.  The writer quit his Public Relations job to take up travel-related challenges and to build an experiential company

The writer quit his Public Relations job to take up travel-related challenges and to build an experiential company

First Published: Jan 14, 2017, 06:47

Subscribe Now