FILA Outstanding Startup of the Year: Udaan

In just two years since the beta launch of its app, Udaan becomes the fastest homegrown startup to snag a billion dollars in valuation

(From left) Amod Malviya, Sujeet Kumar and Vaibhav Gupta, the co-founders of Udaan

(From left) Amod Malviya, Sujeet Kumar and Vaibhav Gupta, the co-founders of Udaan

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India[br]It was a fairly straightforward plan. Build an empire so big that it intimidates competitors by its sheer size. Build a bulwark so tall that it cannot be breached. But winning battles is no walk in the park.

Vaibhav Gupta, Sujeet Kumar and Amod Malviya had fought similar battles before, albeit as generals to Flipkart founders Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal, overseeing its transformation from a fledgling startup to an ecommerce powerhouse. They knew the art of moving mountains.

When Kumar and Malviya, who quit Flipkart in mid-2015, visited Gupta—then on a sabbatical—in Seattle in October 2015, the trio realised over multiple conversations, including one on a drive from Las Vegas to Los Angeles in a convertible Mustang, that marshalling troops as generals wasn’t their calling. They would rather team up to hunt for the next big idea. “We decided that the clinching factor for us should be big markets,” says Gupta.

“Only a few things came up, like commerce, financial technology, electric vehicles. We were more comfortable with (business to business, B2B) commerce and it wasn’t surprising,” says Kumar. “The years we had spent at Flipkart gave us enough exposure on the structure of the market. We had a good idea about how consumption happens and the available infrastructure.”

Back in 2015-16, India wasn’t a fertile ground for B2B startups. Venture capital firms weren’t stoked either. Incumbents were largely vertical focussed—for instance, Industrybuying, Power2SME and Moglix specialised in industrial products, Bizongo on packaging materials, Shotang on electronics and accessories. Horizontal platforms such as Wydr, Tolexo (a unit of IndiaMart, which recently listed on the bourses) or ShopX were yet to find a firm footing. Also, neighbourhood retailers, their potential customers, weren’t at the helm of the smartphone and internet revolution in India.In such a time, Gupta, Kumar and Malviya, it seemed, were punching above their weight. “We wanted to do everything,” says Kumar. For the trio, “everything” went beyond a wide array of categories. “We were clear that it (B2B) cannot be solved independently. That lending, logistics, fulfilment, payment and commerce were integrated problems. That’s why we started building all of them from day one,” adds Gupta.

The proposition has merit, says Anil Kumar, chief executive at RedSeer Consulting. “About 65-70 percent of India’s B2B supply chain is unorganised. There is need for predictability on where the product needs to reach, how long it would take, inventory level and how the demand can be increased, but all those elements are missing,” says Kumar. “A retailer, distributor, wholesaler or a brand wants to have visibility on the entire supply chain. Efficiency is a massive challenge. Then, by the time a product reaches a retailer from the manufacturers, a lot of the profit pool is being eaten up by intermediaries who aren’t adding any value. All such challenges can be effectively addressed by an internet platform.”

RedSeer estimates the B2B retail market to grow at a compounded annual rate of 10 percent from about $714 billion in 2019 to $1,262 billion in 2025. Online businesses will account for at least 4.8 percent of the overall pie from 0.24 percent currently.

Back in 2015-16, the trio’s visit to several wholesale markets in India—Khetwadi in Mumbai, Chawri Bazaar in Delhi, the automotive and electronics components markets in Aurangabad to name a few, each of which witnesses transactions worth at least ₹10,000 crore annually—hinted at a greenfield opportunity. By February 2016, they had decided that, if anything, their venture had to be a B2B marketplace.

To a buyer, they would provide the largest variety at the lowest cost. A seller would get the largest reach at the lowest cost of distribution. “It is a business that requires largescale operations with a high degree of efficiency. If you don’t have scale, you don’t have a long term competitive advantage,” says Gupta.

Gupta, Kumar and Malviya have been running at a frantic pace ever since with Udaan (flight) to ensure that their maiden stab at entrepreneurship doesn’t end up becoming their flight of fancy.

Udaan lets about 25,000 manufacturers, wholesalers, importers and brands sell their ware to approximately 3 million small and medium businesses across 900 Indian cities, about half a million of them transacting every month. It services about 5 million monthly orders across categories such as fashion, electronics, pharma and food among others. Others such as industrial, construction and hardware will be rolled out soon. It also runs an NBFC, Hiveloop Capital.The firm currently clocks an annualised gross sales run rate of $2-2.5 billion. Udaan is also the fastest homegrown startup to snag a billion dollars in valuation, in about two years since opening for business through a beta launch of its app in November 2016. In comparison, Flipkart took about six years.

“The validation had happened before (November). We didn’t launch the app first and then go about validating the concept. It is important to understand that a product should be relevant to be accepted. Our own hypothesis and learnings from Flipkart were that it was highly unlikely that the first version of the app would be perfect,” says Kumar.

It wasn’t the case at Udaan either.

Initially, the company hit hurdles in payments, product cataloguing and discovery as well as logistics. When the founders went back to the drawing board to find the reason behind each roadblock, more often than not they realised they still had a B2C hangover.

For instance, initially Udaan offered an option to pay with credit cards, debit cards, cash and net banking, as was the case with the likes of Amazon and Flipkart. But it had missed a point. In B2C ecommerce, buyers don’t expect a change in price depending on the mode of payment. In B2B trade, however, cash payment entails a lower price than credit. “And in B2B, only two modes of payment work, cash or credit. We never modelled for that,” adds Gupta.

Similarly, returns in B2C are fairly straightforward—they happen largely because either the products were damaged or the correct order wasn’t delivered. Customers either get a refund or credits that can be used to buy anything on the platform. B2B has more layers, explains Kumar. For instance, here the buyers can also be coaxed to keep the order against some credit or additional discount. “This is the language of trade. They (traders) understand this,” he adds.

Udaan is, in fact, all about talking the language of the traders. Here, they have their ears to the ground, says Bejul Somaia, partner at Lightspeed India Partners Advisors, Udaan’s first institutional investor. Lightspeed invested $10 million in the firm in October 2016, even before the product was launched, at a pre-money valuation of $30 million.

“They understand their audience and leverage it to build products that enable users to trade the way they want to, rather than forcing buyers and sellers to modify their business practices and conform with a rigid set of rules. Udaan has a very stakeholder-centric approach,” says Somaia.

*****

Udaan has the reach, scale, financial heft and ambition. While this makes it the leader of the pack, there is also a faint chance that it may occasionally wobble under its own weight. Even a temporary slip can send a chill across many spines. After all, the firm, last valued at about $2.7 billion post money, has roughly $870 million from a clutch of investors riding on it.

“Continuing to manage buyer and seller experience and building supply chain capability that supports a range of horizontal categories at scale is challenging,” says Lightspeed’s Somaia. “On the credit side, they have an advantage because of the proprietary transaction and trade settlement data generated by the commerce marketplace. That said, scaling credit to SMEs (small and medium enterprises) has to be done carefully as this is a segment which has historically been challenging for financial institutions.” Through Udaan, a buyer like a local kirana store would get the largest variety at the lowest cost

Through Udaan, a buyer like a local kirana store would get the largest variety at the lowest cost

Image: Mansi Thapliyal / Reuters[br]Also, B2B ecommerce is a tricky business. The segment has seen casualties such as Tolexo, Shotang, Wydr and JustBuyLive. It takes money and time to build a business worth its salt, says a founder of a B2B startup. “If you want a retailer to buy from you, not only do you have to give him better price, selection, convenience, but also better terms of credit and simplify his payments. On top of it, you have to wean him away from local relationships he has had with distributors for decades,” he says.

Udaan has the money. It can afford to be patient. The firm has managed to circumvent some of the challenges because of its massive war chest. For instance, for quite some time, Udaan didn’t charge a commission from sellers to drive adoption. This was because, at the outset, wholesalers formed a significant chunk of Udaan’s seller base, who would have desisted from offering the best price to retailers had they been constrained to part with commissions they earned from manufacturers and brands. The scenario is gradually changing with brands and manufacturers, swayed by Udaan’s scale, starting to sell directly on the platform.

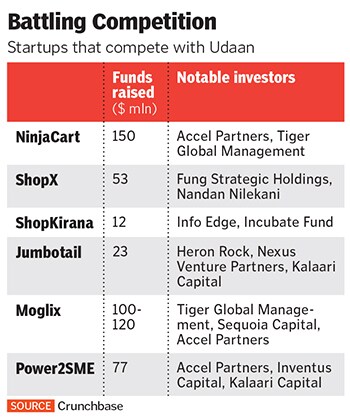

Structural challenges apart, Udaan has a clutch of competitors to stave off. Startups such as ShopX, Jumbotail, NinjaCart and ShopKirana in the food and FMCG segment are sniping at its heels. Large-ticket segments such as industrial aren’t going to be a cakewalk either, with incumbents such as Power2SME and Mogilix poised to give a good fight. Bookkeeping apps such as OkCredit and Khata Book, which also aspire to enable commerce and lend, could end up looking a lot like Udaan.

Also in the fray are heavyweights such as Reliance Industries [owner of Network 18, the publisher of Forbes India], Metro AG, Walmart and Amazon. Metro, which clocked ₹6,100 crore in sales in India in FY18, has launched an app for retailers. Walmart India, which clocked sales of ₹3,600 crore in the same period, is expected to ramp up India operations.

Then comes Reliance Industries’ highly anticipated “new commerce”, which, according to its chairman Mukesh Ambani, will be a “user-friendly digital platform designed for inventory management, customer relationship management, financial services and other services”.

Also, unlike yesteryears, marquee investors such as Tiger Global Management and Sequoia Capital, among others, have started taking interest in the B2B segment, which implies that some of Udaan’s smaller rivals may also have access to capital.

Being a full stack service provider and a horizontal marketplace will play to Udaan’s advantage, says Utsav Somani, partner at AngelList India. “It has the economics of scale on its side.”

The trio at Udaan is mindful of the challenges. A lot of cash is being deployed to fortify the company. “If you make the right choices and invest in them, then, when the platform scales, the more durable it becomes and the return on investments is high,” says Gupta.

A humble submission follows the postulation. “It’s not like we have a solution to all the problems. We are still learning.”

First Published: Nov 25, 2019, 12:15

Subscribe Now