Gayathri Vasudevan's labour of love

By enabling seven lakh livelihoods in the informal sector, the LabourNet CEO is aiming to build a profitable, ₹1,000-crore innovative learning company in four years

Gayathri Vasudevan, CEO, LabourNet

Gayathri Vasudevan, CEO, LabourNet

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Forbes India Leadership Award 2018: Entrepreneur With Social Impact

It was an offer that Gayathri Vasudevan couldn’t refuse. Not because it was the most compelling of them all. But because it was the only one she had.

“That was the slimiest experience of my life.”In the one year that she spent crisscrossing the volatile terrains of Bihar, Vasudevan had let nothing, not even patriarchy and inter-caste strife, thwart an extensive research she was leading on behalf of the Institute for Human Development, a Delhi-based research non-profit, on the state of affairs in 30 villages. She had always managed to chart her way into the hinterlands to study development, often coaxing fractious politicians and their affiliates to let her enter their fiercely-guarded territories.

But, that overcast morning in 1999, when she set out for a marooned village in Nalanda district, Vasudevan was up against nature. The Ganga was overflowing and no boatman was willing to brave the turbulent river.

“I was arrogant enough to say that I will have to go now. They said, there is a buffalo, sit on it. There were a couple of foreign interns with me and I was supposed to lead the research delegation. And I did not know how to swim. I was trying hard not to look terrorised,” says Vasudevan, grinning.

A while later, after some hemming and hawing, she was on the muck-covered buffalo.

It was a big leap of faith for the city-bred Vasudevan, daughter of an Indian Administrative Service officer. Growing up in Bengaluru and Delhi, she had almost everything at her beck and call. Poverty, unemployment, health care, or the lack of it, were largely living-room ruminations. For her, a management degree from a reputable institute was meant to be a stepping stone to a a plum job.

But, that was not to be.

In the early 1990s, Vasudevan, then a student of economics in Delhi’s Jesus and Mary College, was jolted out of her cocoon. It was a time when the capital was burning with protests against the Mandal Commission a battery of youth attempted self-immolation to protest caste-based reservations in government jobs. Closer home, on Delhi’s Sardar Patel Marg, Vasudevan saw a number of young men and women in a neighbouring dhobi ghat (washerman’s colony) and a Kashmiri rehabilitation colony burning daylight—the exact opposite of her milieu, who were toiling in schools and coaching classes to get through the hallowed gates of the Indian Institutes of Technology.

“On the one hand, I was reading about the Mandal agitation, which had an indelible impression on me. At the dhobi ghat, I could see that children wouldn’t go to school or college. They were dropping out. They were just hanging around. In the Kashmiri rehabilitation colony, there was a lot of anger about migrating to Delhi,” says Vasudevan.

“I realised there was a world outside that doesn’t have the access that I had. This changed the path I wanted to take in life, so I decided to study social work,” says Vasudevan.

Life was no different during her two years at College of Social Work, Nirmala Niketan, in Mumbai. Much of her time was spent in the slums of Khar, Bandra and Behrampada, ravaged by the riots of 1992 and then attending to the victims of the cataclysmic earthquake the year after that ravaged Maharashtra’s Latur district, 500 km from Mumbai.

“In some way, such incidents change your life track. Such magnitude of pain and tragedy has its own impact on you and what you want to do with life,” she adds.

Consequently, Vasudevan’s professional life has revolved around enriching the lives of others, even if it occasionally left friends and acquaintances flummoxed with actions that could be construed as impetuous.In February 1996, barely six months after giving birth to a daughter, Vasudevan, then pursuing her PhD from Institute for Social and Economic Change in Bengaluru, packed her bags to live in Maldare, a village in Karnataka’s Kodagu district. The aim was to spread awareness about reservation for women in panchayats and municipalities. The flip side was, until then, Vasudevan was accustomed to being served, a way of life impossible amid the vagaries of village life. She struggled, with cooking, cleaning and attending to her new-born.She survived the odds, and, by the time she left Maldare in 1998, Vasudevan had set up a grain bank run by women. Also, the women in the panchayats, who were earlier largely titular heads with men taking key decisions from behind the scenes, were completely in charge.Vasudevan shocked her friends yet again with her decision to quit the International Labour Organisation (ILO), a United Nations agency, in 2006, a job that earned her $5,000 as salary every month. “Everybody said, I was nuts. I had joined in 1999, and had I spent two and a half years more I would get a pension.”Her reason to quit was simple. “It was a huge learning on how the government works, how policy works. In a village, other than writing papers [for her PhD], I was not accountable to anybody. Here, you are accountable, you have to do things according to rules and regulations,” says Vasudevan. “I was very tired of the bureaucracy. I was meeting the top people, ministers and district collectors, but the feeling of inadequacy was there. I felt I needed to implement myself more.” *****

LabourNet, a company Vasudevan now runs out of a nondescript office in a narrow alley in Bengaluru’s JP Nagar, is a melting pot for some of the key takeaways from her travels in rural India and her stint at ILO. With LabourNet—started as a project by Bengaluru-based non-profit Maya in 2007—Vasudevan aims to provide livelihoods to India’s informal sector workforce. A May 2018 study by ILO estimates that 81 percent of employed Indians work in the informal sector, second only to Nepal’s 90.7 percent among South Asian countries. She aims to bridge gaps in education, employment and entrepreneurship.

“Gayathri believes that once a person gets a job, we have to work with them to move them up the ladder. Just a job has no meaning and wage is the key problem. The entire activity that we were doing at LabourNet is primarily to look at whether somebody’s wage has increased and not just if somebody has just got a job,” says Rajesh A, executive director at LabourNet.

LabourNet has created 135 certification courses for 28 industries, including construction, apparel, leather, rubber, beauty and automobiles. A job seeker may take up these courses against a fee. The training is either conducted on the shop floors of private companies and small and medium enterprises, which intend to absorb LabourNet-certified professionals into their workforce, or at centres run by LabourNet. The firm also runs vocational courses in schools, and helps people turn entrepreneurs—for instance, set up a beauty parlour or a mechanic workshop—by going the whole nine yards, from arranging finance to bookkeeping. It also runs a placement service for job seekers at MSMEs.

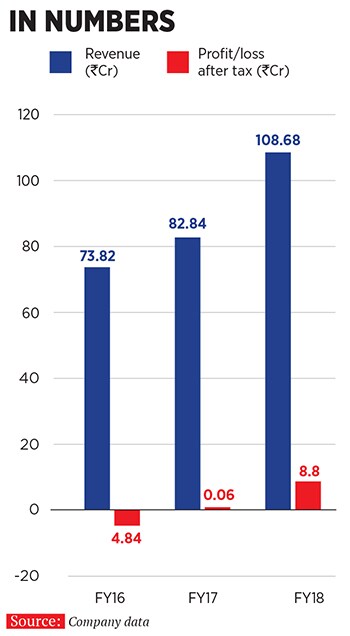

The idea seems to working. LabourNet posted ₹8.8 crore in profit after tax on revenues of ₹108.8 crore in fiscal 2017-18. Vasudevan says the company, which has touched 7 lakh people so far, has been profitable for the last two fiscals.

*****

Business wasn’t as hale and hearty always. But, the management, led by Vasudevan, have been quick to identify the chinks in their armour and fix them. For instance, when Vasudevan joined them in 2007, LabourNet was connecting service providers such as electricians, drivers, masons and plumbers with consumers. Maya, the non-profit that started the venture, operated a call centre, somewhat like a predecessor to today’s venture capital-backed hyper-local home service providers such as UrbanClap and Housejoy.

Vasudevan was keen on transforming the project into a full-fledged business. “In a not-for-profit, your funding determines your goals. The donor becomes very powerful and you are not mission-focussed, which I felt was not right,” says Vasudevan.

Vasudevan incorporated LabourNet as a private company in 2008. “I was allowed to do that because there was no money. Any money that was being put in was my own money. The grant money that had come from Ford Foundation was long exhausted,”

A spike in business, however, looked like a pipe dream. So, in 2011, after the company exited the fiscal with a measly turnover of ₹40 lakh, Vasudevan took a hard look at the business. She realised that solving the problem of information asymmetry alone wouldn’t help LabourNet grow. “You need certification and continuous learning to upskill the workforce. Also, it was a little ahead of its times, and maybe the technology wasn’t good enough to support this kind of a business,” says Vasudevan.

The company had hit another roadblock in fiscal 2015, when an earn-and-learn model introduced a year earlier failed to take off. Vasudevan stepped in by raising a bank loan against her house as a collateral.

Rajesh says Vasudevan has always been selfless when it comes to building LabourNet. During the pivot in 2011, when she urged Rajesh and a clutch of industry veterans to join her, Vasudevan didn’t blink before parting with equity. “Everything was on the table for discussion. Gayathri was ready to change the way they were working and there was no ego. Her only ask was, it should create impact,” says Rajesh.LabourNet has raised about ₹35 crore in equity and debt from Michael and Susan Dell Foundation, Acumen Fund, NSDC, angel investors.

Angel investor Reena Mithal describes Vasudevan as a people’s CEO, who doesn’t shy away from getting her hands dirty. Mithal recalls an incident in early 2012 at a construction site outside Bengaluru, which also doubled as a training centre for LabourNet. Vasudevan mingled with the trainees and, much to Mithal’s surprise, lent a hand to some masonry work. “This helps build confidence in the company,” says Mithal.

While people skills have always been her forte, Vasudevan has evolved as a business person as well, adds Mithal. “Earlier, Gayathri would at times just spell out the problems in a board meeting. Now, she is more forthcoming in not only stating the problems but also suggests possible solutions.”

Vasudevan has some lofty plans for LabourNet. The goal is to become a ₹1,000-crore revenue company and touch at least 10 million people by 2022.

Naga Prakasam, partner at Acumen Fund, believes the goal isn’t far-fetched. After all, they have got people to pay for the courses. “LabourNet has grown more than many skilling companies and non-profits. A private company in this space, taking equity investment and reaching ₹100 crore in revenue, is fantastic,” says Prakasam. “The next thing that Gayathri needs to prove is that this scale is also possible without aide from government programmes like Skill India, and have people pay for it. For people to pay, the outcome needs to be clear. If they see the scope for earning more by taking up a course, they will pay. An NIIT or an Aptech thrived because people were willing to pay as they got jobs.”

The opportunity is big. The goal is clear. And Vasudevan means every word when she says, “We want to formalise the informal sector. The idea is not to give doles and benefits, but to empower people to make a better living.”

First Published: Nov 22, 2018, 17:20

Subscribe Now