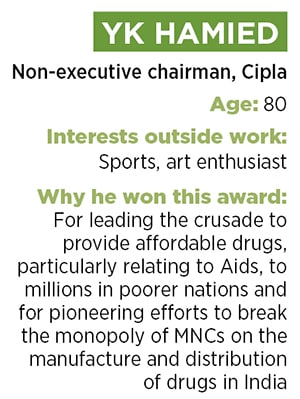

YK Hamied: Cipla's fearless crusader

Cipla's YK Hamied is no ordinary business leader. He is a pioneer and a disruptor who has significantly changed the global pharma landscape in his over 50-year professional career

Image: Vikas Khot

Image: Vikas Khot

In 2000-01, the HIV/Aids threat had intensified across sub-Saharan Africa, affecting millions. To compound the problem, the medicines that could help treat the condition were prohibitively priced, making them unaffordable for the socio-economically under-privileged patients in the region. It was at this juncture that an idea changed their lives, the drug industry, and the shape of one Indian pharmaceutical company in particular.

Yusuf Khwaja Hamied—inspired by a chance read of a medical journal—decided to create a “triple cocktail” of drugs, at a fraction of their original price, which would help control and manage the disease. The product, called Triomune, comprised stavudine, lamivudine and nevirapine (three ingredients that were being manufactured and sold independently under different brand names by various drug companies). Triomune was manufactured by Cipla at its three plants—one each in Mumbai, Patalganga (in Raigad district, outside of Mumbai) and Bengaluru.

Hamied, then chairman of Cipla, offered this tablet to global non-governmental organisation Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) for distribution at $350 (Rs 15,750, with $1 equalling Rs 45) per patient per year, compared to $12,000 (Rs 540,000) per patient per year that the combination of the prevailing individual drugs cost in 2001. The global companies that manufactured these three drugs had no option but to reduce prices.

(Since then, other Indian companies have offered variants of the cocktail, at between $50 and $60 per patient per year. Cipla, however, does not manufacture Triomune anymore.) “Hamied was completely fearless. When I first met Cipla officials, I was struck by the fact that they were not in awe of multinational pharma corporations,” recalls Leena Menghaney, South Asia head of MSF’s Access Campaign, who first met Hamied in 2005.

“Hamied was completely fearless. When I first met Cipla officials, I was struck by the fact that they were not in awe of multinational pharma corporations,” recalls Leena Menghaney, South Asia head of MSF’s Access Campaign, who first met Hamied in 2005. Cipla had little reason to fear. As Hamied points out, it was legally allowed to produce its own version of the three drugs because Indian patent laws at the time decreed that patents applied only to the processes by which the drugs were made, and not the product itself. Also, Cipla had assuaged any quality concerns surrounding Triomune by sharing its drug dossier with MSF. It further agreed to bio-equivalence testing and allowed for good manufacturing practice audits. It also provided the drug for a trial, which proved its efficacy. It went to market in 2001-02.

Cipla had little reason to fear. As Hamied points out, it was legally allowed to produce its own version of the three drugs because Indian patent laws at the time decreed that patents applied only to the processes by which the drugs were made, and not the product itself. Also, Cipla had assuaged any quality concerns surrounding Triomune by sharing its drug dossier with MSF. It further agreed to bio-equivalence testing and allowed for good manufacturing practice audits. It also provided the drug for a trial, which proved its efficacy. It went to market in 2001-02.

This battle—perhaps, Hamied’s greatest ever—was fought nearly 15 years ago, but the story has not lost its significance. It is one that put Cipla and Hamied on the international map, while changing the dynamics of the global pharmaceutical world.

“My entire work has been to ensure that all in the poor and developing world have access to medicine at affordable prices,” Hamied, now the non-executive chairman of Cipla, tells Forbes India over the phone from Marbella in Spain, where he is recuperating from a surgery.

Over multiple telephone conversations, the Cambridge-educated billionaire was his typical suave, accommodating and courteous self. His personal demeanour, however, belies his assertive professional approach. After all, he is among the few Indian scientists and businessmen to have successfully taken on the might of hard-nosed multinational drug companies in several battles over issues such as monopoly in drug manufacturing, patents, and providing medicines at affordable prices.

Now 80, Hamied shows almost no signs of slowing down. He is still involved in strengthening the landscape for the pharmaceutical industry as well as the role of the company that his father set up in 1935.

His niece Samina Vaziralli, 38, his brother Mustafa’s daughter who was elevated to executive vice chairman this August, has been positioned as the next-generation leader from the family, who will be providing the vision of the promoter-family. She had joined the company in 2011, and is now the only member of her generation actively involved with the business.

After Yusuf Hamied stepped down as Cipla’s managing director in 2013, his nephew Kamil Hamied, who was chief strategy officer, was being groomed as the heir apparent. But in 2015, Kamil moved out to pursue personal interests. Cipla’s day-to-day operations are run by a professional management, while Yusuf Hamied and his brother Mustafa continue as non-executive directors.

Cipla claims to be India’s largest standalone (not taking into account companies associated through mergers and acquisitions) pharma company, with total revenues of Rs 12,293.20 crore for FY16 it generated sales of Rs 3,594 crore for Q1FY17. About 40 percent of its revenues come from domestic sales, and its best-selling products globally are respiratory, urology and paediatric medicines. Graphic: Sameer Pawar

Graphic: Sameer Pawar

THE INDIANNESS MOTIVE

Growing up among the leaders of India’s freedom struggle, the desire to challenge the dominance of multinational drug companies in independent India was strong in the Lithuania-born Hamied.

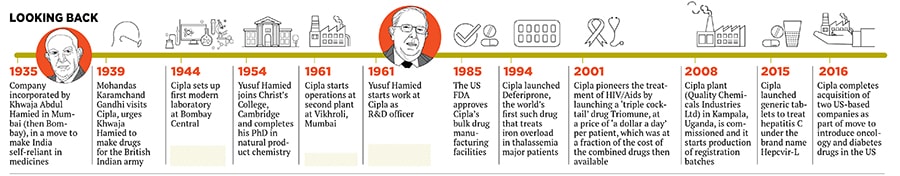

His father Khwaja Abdul Hamied, also a scientist, had set up Cipla (originally called Chemical, Industrial and Pharmaceutical Laboratories) in 1935 to help make India self-reliant in health care. He had used funds generated from the import of typewriters, sewing machines and a German tonic called Okasa that cured male impotency.

In 1939, when World War II broke out, imports of Okasa stopped and Hamied’s father developed processes and formulas to manufacture the tonic out of Cipla’s first laboratory in the Bombay Central neighbourhood of Mumbai. Imports of the typewriters and sewing machines stopped.

In the same year, one event triggered a transformation in Cipla’s future, recalls Hamied. On July 4, 1939, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi visited Cipla to meet Hamied’s father. “He told my father that, due to the war, imports of medicines had stopped. Gandhi wanted us to manufacture medicines for the British Indian army,” Hamied says.

That was when Cipla started manufacturing qinarsol (for malaria), cardiamid (for trauma), emetime (for diarrhoea and dysentery), and vitamins C and B12 at its Bombay Central laboratory. “We did not need to [hard-] sell Cipla after that [Gandhi’s visit],” Hamied says. In 1961, Cipla set up another factory at Vikhroli in Mumbai.  Staff members of Bengal Immunity interacting with YK Hamied in Calcutta in 1966

Staff members of Bengal Immunity interacting with YK Hamied in Calcutta in 1966

Image: Cipla Archives

But the company was still far from achieving substantial size. In 1947, Hamied says that the Indian pharmaceuticals industry was approximately Rs 10 crore in size (by revenue), and Cipla was just Rs 20 lakh.

The young Hamied, however, was yet to enter the fray. He had just completed his O Levels from the Cathedral and John Connon School in Mumbai, when his father, who was the city sheriff, met Alexander Todd, a visiting professor of chemistry from the University of Cambridge Todd was knighted in 1954, and won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1957.

“My father asked Todd about the minimum qualifications for a student to study at Cambridge, to which Todd said, ‘We have no such rules. If we like the boy and if we feel he is suitable, we take him. No minimum qualifications’.” Hamied joined Christ’s College, Cambridge, in 1954, without doing his A Levels. “If I had not met Todd, I would not have been here today luck and fortune play a very important role in life,” says Hamied. He completed his PhD in natural product chemistry and came back to India in 1960, and joined Cipla in 1961. Hamied with wife Farida

Hamied with wife Farida

Image: Cipla Archives

It was a tough initiation for the 24-year-old. In those days, if you were related to a director in a public limited company, your job appointment would have to be approved by the Company Law Board (this is no longer the case). Eighteen months after returning to India, Hamied became a research and development officer at Cipla, at a salary of Rs 1,500.

The Indian pharmaceutical industry—and Cipla itself—was very different then. “At that time, the import duty on end-products was 100 percent, and the import duty on raw materials to make that end-product was 146 percent. It was a deterrent, but we went ahead,” says Hamied. “When we could acquire an import licence (for example, of Rs 2 lakh) in the late 1960s, office mein ladoo bat te the [sweets were distributed in office].”

In 1960, Cipla’s annual sales were Rs 48 lakh. “It was not even in the top 50 pharmaceutical companies in India,” Hamied points out.

It was the 1960s, and India’s population had started rising alarmingly. As one of his first initiatives, Hamied started focusing on producing steroids and hormones that could help in family planning, he says.

Hamied (far left) and his father (second from right) at the biochemical section of the Cipla laboratory in Mumbai with Sir Alexander Todd (far right) in 1960

Image: Cipla Archives

The 1960s were also a time when multinational drug companies such as Pfizer, Hoechst, Roche, Abbott, Parke- Davis and Boots were the dominant players in the country. Hamied realised that if Indian companies were to make a mark, they would have to start manufacturing APIs (active pharmaceutical ingredients). Indian pharma companies started the large-scale manufacture of APIs only in the 1970s this would accelerate further in the 1980s after local patent laws were revised.

This is where Hamied’s tenacity played out.

In 1961, Hamied and a few like-minded businessmen formed the Indian Drug Manufacturers Association (IDMA) to lobby the interest of the domestic pharmaceuticals industry and consumers. But it took another 11 years for the draconian Indian Patents and Designs Act 1911 to be modified, Hamied says. “India used to recognise both product and process patents. No one except the patent holder was allowed to manufacture a patented drug in India, even by an entirely different process,” wrote Dr RD Lele, founder and director of Mumbai’s Jaslok Hospital’s nuclear medicine department, in a 2005 report published by the IDMA. The patent holder could monopolise the manufacture of the drug for 20 years, and was at liberty to decide both its availability and price, Lele wrote. “For a country just trying to raise its head from its colonial past, this was a huge burden,” he pointed out.

These macro conditions forced India, under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to modify the rules of the game, especially for the health care and food sectors. India abolished product patents in these areas, but allowed process patents for seven years. This meant one could not patent an end-product, but could patent the process to make it for a period of seven years. The Patents Act 1970 was passed in 1972.

“This gave Indians the legal freedom to copy any drug that India required, which was patented and available overseas,” Hamied says. “Even at that time, we did not oppose patents we opposed monopoly.”

“Cipla championed the cause for reforms to the Patents Act 1911. This led to the taking down of monopolies of MNCs for the next 33 years, and was the most profound effect any company has had on policy-making,” says MSF’s Menghaney. “The genesis of the generic drug making industry in India—in terms of technology, capacity and volumes—is largely due to the reforms of the patents act in the 1970s.”

THE GOLDEN YEARS

In 1972, Hamied took charge of the business after his father passed away. The next three decades were fruitful for the Indian pharma industry: Drug formulation production grew, and prices of antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, cardiovascular and anti-cancer drugs became cheaper, and more accessible, in the country.

Hamied (centre) visits Cipla’s facility in Goa in 2002

Hamied (centre) visits Cipla’s facility in Goa in 2002

Image: Cipla Archives

This period also saw the emergence of several large Indian pharma companies, including the erstwhile Ranbaxy Laboratories, Wockhardt, Cadila, Lupin and Unichem. This gave an impetus to pharma exports, which continue to comprise mainly of generic drugs. From a meagre $48 million (Rs 615 crore) in the early ’70s, exports have risen to about Rs 105,216 crore in FY2016, by government estimates.

This coincided with the rise of Cipla too. Even in 1972, Cipla had sales of Rs 1.6 crore, and ranked a lowly No. 56 among Indian pharma companies.

In 1985, Cipla became the first Indian company to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (US FDA). Since then, the company has executed over 20 US partnerships and has supported the development of more than 170 abbreviated new drug applications.

By FY2001, Cipla became one of the top 10 Indian companies by sales, with revenues of Rs 1,086 crore. Therapeutic segments, especially the anti-asthma and cardiovascular groups, saw strong growth. In 2001, Cipla launched at least 20 new formulations, including axalin (for cough associated with bronchitis), cobix (inhibitor for arthritis), dinex (anti-retroviral for HIV/Aids), docetax (for various forms of cancer) and duolin (bronchodilator combination therapy for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases).  Late President APJ Abdul Kalam presenting the Padma Bhushan to YK Hamied in 2005

Late President APJ Abdul Kalam presenting the Padma Bhushan to YK Hamied in 2005

Image: Cipla Archives

2001 was also the year of Triomune. But the origins of the game-changing drug were not just in that journal article Hamied had read they dated back to 1991, when Aids itself was brought to Hamied’s attention by AV Rama Rao, founder-chairman of Avra Laboratories, a contract research and manufacturing services company in Hyderabad. Rao had approached Hamied with the synthesis to create an anti-retroviral azidothymidin (AZT). Hamied accepted the challenge and was ready to commercially produce AZT in 1993. But the 100 mg capsule, priced at $2 (Rs 60 at that time), proved too costly for end consumers also, the distribution was weak. Cipla pulled the plug on the drug in the same year, and stayed away from Aids medication till 2001.

Hamied, however, views this project as awareness-building. “If Rao had not come in 1991, I might not have looked at it [in 2001].”

By 2005, Cipla was catering to the needs of approximately 120,000 HIV-positive patients worldwide, and supplying anti-retroviral medications to 90 countries and triple drug cocktails to 43 countries.

Dr Peter Mugyenyi, a Ugandan physician who is now recognised as one of the most prominent global researchers in HIV/Aids, says: “[Hamied] could have come to Africa as a businessman wanting to make money by selling medicines. But he came to provide treatment to millions from another country.” Mugyenyi was among the few who did not support a challenge from activist groups over patent legality (when Cipla offered Triomune in Uganda).

Cipla, too, has gone beyond just exporting to Uganda, and has set up a factory in Kampala to manufacture anti-retroviral and anti-malarial drugs. “You know the story about the man who offered fish to a hungry man. But Hamied is the one who taught the man how to fish,” says Mugyenyi, who is also on the board of Cipla.

GOVERNMENT CONCERNS

Though Cipla, and the Indian pharma industry, has gone from strength to strength, the patent law monster was going to come back to bite them.

By the early 2000s, India had adopted World Trade Organization (WTO) guidelines for various sectors. This impacted patent laws too. In 2005, the government re-amended the Patents Act of 1970 by deciding to recognise product patent applications for all molecules after January 1995. “This worsened the situation,” Hamied says.

Jaslok Hospital’s Lele, in the 2005 IDMA report, wrote that the fresh amendments would have far-reaching consequences, particularly on the easy availability of modern drugs. For instance, under the amended patent laws, Cipla, like several other Indian pharmaceutical companies, cannot produce the next generation of cancer medicines in India without permission from MNCs.

Hamied has, in recent years, called for a pragmatic in-licensing for patented and monopoly drugs developed abroad. His suggestion is an automatic licensing system, where a company pays royalty to the originator company with the product patent, and produces and markets the medicine to the developing world.

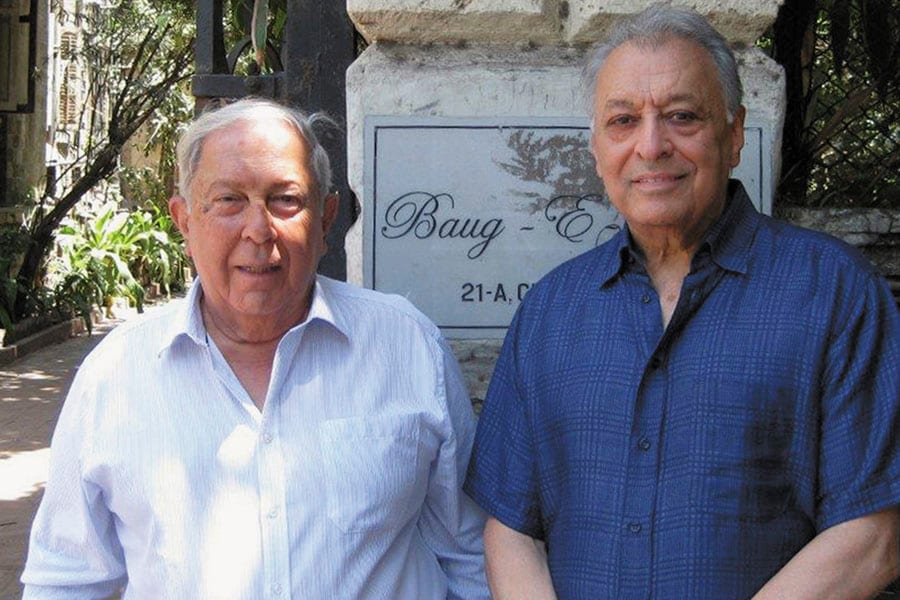

Hamied with childhood friend and music conductor Zubin Mehta

Image: Cipla ArchivesIn his career that has spanned more than 50 years, Hamied has been viewed as “pirate” or “messiah” by those who are on either side of the debate on protection of patents versus providing affordable medicines to all.

Hamied pays little attention to his critics: “If I’ve broken some law, I need to be prosecuted. Why has Cipla or YK Hamied not been prosecuted? I live by the law of the land and have done nothing illegal.”

He is unrelenting in his war against patents, and, at the same time, has an eye for innovation and opportunity many consider these to be his greatest strengths.

For instance, in 2005, when fears of H1N1 (or avian/bird flu) were widespread in India, Hamied met Dr M Venkateswarlu, the former (late) drug controller general of India, who also happened to be a friend.

“I asked him what the government would do if bird flu hit India in a big way. He smiled, threw his hands up in the air and said we would surrender. I told him that when you surrender, I will take up the challenge,” Hamied says.

He recalls calling up his R&D team, urging them to stop all other work, and focus on all the literature they could gather on a drug called oseltamivir (this was as an anti-viral drug, branded as Tamiflu, marketed by Roche). The starting synthesis for oseltamivir was a Chinese chemical called shikimic acid, found in the spice star anise. Over the next three months or so, Cipla managed to reduce the steps in the manufacture process from Roche’s 20 to 12, and came up with a cheaper version of Tamiflu, called Antiflu.

The starting synthesis for oseltamivir was a Chinese chemical called shikimic acid, found in the spice star anise. Over the next three months or so, Cipla managed to reduce the steps in the manufacture process from Roche’s 20 to 12, and came up with a cheaper version of Tamiflu, called Antiflu.

Roche, however, went to court, and although Cipla won the case and was allowed to manufacture and sell Antiflu, the Indian government stopped Cipla from selling it as a medicine for seasonal flu.

CIPLA TODAY

As the global economic environment changes, so does the strategy for most Indian companies. Over the past decade most of the country’s generic drug manufacturers have found a strong foothold in the United States and Europe. Cipla, too, has expanded its presence across those regions. It currently has more than 40 commercialised products in the US. In Europe, its 100 percent subsidiary, Cipla Europe NV, has a presence across more than 30 countries through partners and its own network, focusing mainly on APIs, respiratory, HIV and OTC products.

It also has a leading position in other emerging markets like Yemen, Iran, Sri Lanka and North Africa to sell their drugs.

Operating in developed countries also means Indian firms having to adhere to drug regulatory quality norms of those countries. Cipla spends up to 8 percent of its turnover on research and development.

Last year, Cipla launched generic tablets to treat hepatitis C under the brand name Hepcvir-L this is the generic version of the US-based drug maker Gilead Sciences Inc’s Harvoni tablets. Cipla also provides drugs to treat what Hamied calls “often neglected” diseases such as thalassemia, kala azar, pulmonary fibrosis and multiple sclerosis.

The energetic octogenarian’s outlook is future-positive, and he is confident about the role that niece Vaziralli—who had earlier worked for four years in the investment management division of Goldman Sachs in New York and London—is set to play.

“She is very dedicated… from the same [family] stock. She reminds me a lot of Lupin’s Vinita Gupta,” says Hamied. “Samina [Vaziralli] like Lord Todd earlier—has this gift of team-building and having good people around her. That is critical for success. Till 2020, Cipla is very comfortably placed. By then we may be a company of Rs 20,000 crore sales. After that we will have to see where growth comes from.”

At this point Hamied becomes sentimental. “I want the Cipla name to remain in whatever form the company may take in the coming decades, as buyouts and mergers cannot be ruled out.”

For now, Cipla is doing the buying. Only this year, it completed the acquisitions of two American generic drug firms, InvaGen Pharmaceuticals and Exelan Pharmaceuticals, to increase its revenue and introduce new products for oncology and diabetes in the US.

The many achievements of Cipla, though, have a common thread. It all goes back to the nationalistic and, more significantly, humanitarian streak that drives Hamied. Habil Khorakiwala, chairman and founder of pharmaceutical company Wockhardt, says, “Hamied has always been very passionate about India. His view was that drugs from MNCs were very costly. He is that rare scientist who believes and practices the Indianness he believes in.”

Hamied is cognisant of the widespread appreciation and acknowledgement of his contribution to the pharmaceutical world. “But success does not make a company great,” he points out. “What really matters is the contribution it makes towards making life better for everyone. I would love to see India take a stand on what is best for India. We must realise that it is only we who can solve our problems and not the West.”

First Published: Nov 24, 2016, 06:43

Subscribe Now