Siddhartha Lal: The braveheart

He turned an ailing Royal Enfield around and changed the fortunes of Eicher Motors, but Siddhartha Lal is yet to complete a road trip from Manali to Leh on his bike

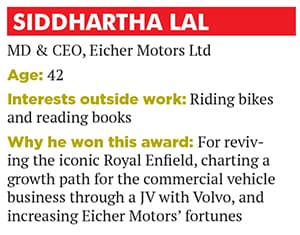

Forbes India Leadership Award: NextGen Entrepreneur

Towards the end of June this year, when Siddhartha Lal, managing director and CEO of Eicher Motors, set out from Manali in Himachal Pradesh on a bike, he had two objectives: Test the two-wheeler, which was a prototype of a new model that Royal Enfield (a division of Eicher Motors) is planning to launch soon, and complete the journey to Leh, Ladakh.The first part was critical as the bike is in its last stages of development. As he rode the motorcycle along the Manali-Leh Highway, Siddhartha, 42, subjected it to various tests and closely observed the performance of the prototype. His focus was rider comfort, and more importantly, whether the bike was in line with Royal Enfield’s brand positioning: To offer its customers a distinctive riding experience and road presence.

The second objective remained elusive. Siddhartha was determined to complete the journey to Leh by road. His failure to do so over the past five years is called the ‘Ladakh jinx’ by friends and colleagues. But as he rode into Keylong, a small town 200 km into the journey, the jinx caught up with him yet again. Flash floods had shut down the road ahead, and he had no choice but to ride back to Manali.

His earlier attempt in 2010 had ended more dramatically as he was stranded with his team at Rumtse, a small village on an elevation of 13,700 feet and 85 km from Leh. A cloudburst had cut off the desert city from the rest of the country. When family and colleagues failed to hear from him for days, panic set in at Eicher Motors’ headquarters in Gurgaon. Siddhartha and his team were later airlifted to safety.

“He is not risk averse,” says Sachin Chavan, head–rides and community, Royal Enfield. Over the last eight months, Siddhartha has been testing the prototype in different terrains across the world. Apart from the test track in Chennai, he has ridden the motorcycle in the UK, across Switzerland and through the Himalayas.

“It is not often that one sees the CEO of a company testing soon-to-be-launched products in adverse and difficult conditions,” says S Sandilya, chairman of Eicher Motors. When the company launched its Continental GT in November 2013, he rode the bike from Goa to Mangalore. “He is passionate about riding, and uses that passion to add value to the company’s product development programme,” says Sandilya.

But then, Siddhartha, who has done his Masters in automotive engineering from the University of Leeds in England, never fitted into any traditional template of leadership. His refusal to be straitjacketed into any one mould has not stopped him from achieving significant success with Eicher Motors. When he took over the reins of the company in 2006, it was a Rs 1,912 crore conglomerate that had spread itself thin across 15 businesses. He has since transformed it into a Rs 9,459 crore company with a clear focus on only two areas—leisure bikes and commercial vehicles. Profits have risen from Rs 212 crore to Rs 701 crore in the same period. And the scale of success is evident in the stock market where Eicher Motors’s share price on the National Stock Exchange moved from Rs 300-levels towards the end of 2005-06 to Rs 18,000-levels as of 2015.

Siddhartha comes from a business family that is unique in many aspects. For one, the Lals are not obsessed with business. “We rarely discussed it at home, and my father (Vikram Lal) gave up his role in the company as soon as he could,” says Siddhartha. (Vikram Lal retired as CEO of Eicher Motors in 1997, and handed over the reins to a non-family professional.)

He was not expected to enter the family business. “Eicher has always been a professionally managed company and that gave Siddhartha all the freedom to make up his mind about what he wanted to do,” says Sandilya, who joined the business in 1975.

When the young scion finally chose to enter the family business, he did so dramatically. He sought a year’s time from his father to revive the ailing Royal Enfield, which the management wanted to sell or shut down. He became CEO of the motorcycle company in 2000 at the age of 26. Between 2000 and 2004, he based himself out of Chennai, where Royal Enfield is headquartered, and got to work. By the turn of this century, Royal Enfield was bleeding, unable to sell even 2,000 bikes a month (its manufacturing capacity was 6,000). The management at Eicher Motors saw no value in it. But Siddhartha saw something different—a distinctive product with a rich history and an army of die-hard fans.

“The easiest option then was to build a commuter bike and arrest the bleeding, but he did not go for it,” says RL Ravichandran, former CEO of Royal Enfield, who has also held leadership positions at TVS Motor Company and Bajaj Auto.

Having worked closely with Siddhartha, first at Royal Enfield (2005-11) to bring about its turnaround, and then as a member in Eicher Motors’ board of directors (2011-15), Ravichandran had a ringside view of how Siddhartha operated. “We had, in fact, built a prototype of a fast bike like a (Bajaj) Pulsar, but he scrapped it,” recalls Ravichandran. “He wanted to retain the basic character and distinctive looks that Royal Enfield products are known for. It was then that I understood Siddhartha’s logic. When you have a unique product, why go where the crowd is? Develop it in a manner that it demands a premium, and not compete for margins,” he adds.

But when it came to emission norms, the CEO was ready to embrace change, and attack the old technology vigorously. A new engine was developed much to the chagrin of Enfield fans, who wanted the bike to retain its older cast iron engine.

It is a telling sign: Siddhartha is focussed and driven, but he is always willing to embrace necessary change, and does not remain too fixated on any one aspect of the business. Ravichandran recalls a situation in 2008 when the company had finalised the specifications of its first bike with the new engine, the Royal Enfield Classic. The future of the brand was riding on this motorcycle.

The original plan was to give it a modern classic look, and Siddhartha was sold on the idea. It then transpired that a retro classic look would work better. “When I broached the idea with him, he asked me a few pointed questions before approving the look,” recalls Ravichandran. Royal Enfield Classic’s success laid the foundation for the ailing company’s revival.

Today, Royal Enfield accounts for 40 percent of Eicher Motors’ turnover, 80 percent of its operating profit and almost all of its net profit as per the first quarter performance of 2015-16. Its business has grown at a compound annual growth rate of 50 percent in the last three years. It sold 3.02 lakh units in 2014.

Ravichandran attributes Royal Enfield’s revival to a single factor: Siddhartha’s ability to decode what the brand stands for. For fans, the motorcycles are about power, independence, adventure and the lure of an empty road. “This understanding gave him a clear idea as to what to do, and more importantly, what not to,” he adds.

“A burst of activity and then I take a back seat.” That is how Siddhartha describes his working style. After setting the stage for the company’s revival, he stepped back in 2004, leaving domain experts to take on a more active role. “I am happy to roll up my sleeves, dive deep and pull out once things are comfortable. I know what I bring to the table, and what I don’t,” says Siddhartha, who relocated to the UK in July this year.

In 2008, for instance, he turned his attention to the joint venture (JV) between Eicher Motors and the Volvo Group. The result was Volvo Eicher Commercial Vehicles (VECV). By all accounts, he spent 700-odd days setting up the process and systems to leverage the complementary strengths of the two JV partners before handing it over to his team.

“I like to mix things up a bit. Doing the same thing for a long time leads to diminishing returns,” says Siddhartha.

Siddhartha’s core management philosophy of ‘less is more’ sets him apart from the rest. “Doing less is doing things much better,” he says, adding that Eicher Motors gets as many as 50 different business opportunities every few months, but does not consider any of them and remains true to its two businesses: Motorcycles and trucks.

“It is easy when sitting on a pile of cash to make the mistake of diversifying and losing focus,” says Siddhartha. “If we do not see a future in our current businesses, it is fine to look for opportunities outside, but we know that both Eicher Motors and Royal Enfield can become global brands.”

Even as late as in 2004-05, Eicher Motors was into 15 different businesses ranging from tractors, trading, consultancy, garments and maps and gears. The environment in the 1970s and 1980s necessitated a diversified portfolio. “We had a lot of component imports from Japan for the trucks, and foreign exchange restrictions that were in vogue then forced us to start a lot of export-oriented businesses,” says Sandilya. Over time, the number of businesses that Eicher entered into grew. When India liberalised its economy and eased foreign exchange rules, these businesses became a drag on the company. “We were doing too many things and we were not the best in any of them,” Siddhartha points out.

In 2004, when he returned to Gurgaon after his stint with Royal Enfield in Chennai, and just before he took over as managing director of Eicher Motors, he went about rationalising the company’s different businesses. Its tractor business was sold to Chennai-based Tractors and Farm Equipment Ltd in February 2005. “Tractors was the first business that Eicher had forayed into, but he (Siddhartha) exhibited little emotional attachment to its sale. Once he sees business logic, nothing stops him,” says Sandilya.

Selling 13 businesses, however, was not easy. At the time, word on the street was that “Eicher is finished” and that the “family is selling out”, but Siddhartha remained unfazed.

In a bold move, he decided to offer Swedish truck major Volvo Group a 46 percent stake in Eicher Motors’s truck business in 2008. VECV has since invested Rs 2,300 crore (bulk of the money was brought in by Volvo as a consideration for the 46 percent stake) to modernise and expand existing facilities.

A new modern range of trucks has been launched and VECV’s market share has risen. It is expected to touch 7.5 percent by March 2018 from the current four percent, says broking and investment firm CLSA in a recent report.

The ‘less is more’ philosophy is also in play when it comes to the pricing of Royal Enfield bikes. “The company [Eicher Motors] has, in fact, exercised prudence by not taking up prices too much so as to expand the overall market rather than solely maximising profitability,” notes the CLSA report.

“This [pricing philosophy] is something he [Siddhartha] has acquired from his father,” says Sandilya. “Even in 1975, when we sought a marginal hike in pricing the tractor that cost Rs 30,370 then, we were asked to give a detailed justification and the decision involved hours of discussion.” The message to the officials then and now is to reduce cost and be lean to maximise returns.

“Opportunistic pricing has never been Siddhartha’s policy,” says Ravichandran. The CLSA report notes that Royal Enfield, too, enjoys strong pricing power for its products given the robust demand and long waiting lists. Its bikes cost anywhere between Rs 1.20 lakh and Rs 2.20 lakh.

Siddhartha has now set his eyes on the global market: He wants to make Royal Enfield an international brand. He has unleashed a burst of activity in London to leverage its British heritage and design products (Royal Enfield has a development centre there) that appeal to the global audience.

In its first avatar, the motorcycle company was called Enfield Cycle Co Ltd, founded in 1893 and based out of Worcestershire in the UK. In the 1950s, it partnered with Madras Motors in India. And while Enfield Cycle Co Ltd is now defunct (it shut shop in 1971), Royal Enfield in India is primed for an international take-off.

“To succeed anywhere, we have to be closer to the market to understand customers better and evolve a strategy,” says Siddhartha.

Siddhartha will, however, visit India often during this period, he says. After all, he has a jinx to break and a journey to complete. The 490-km ride from Manali to Leh beckons.

First Published: Oct 09, 2015, 06:52

Subscribe Now