RC Bhargava: In the driver's seat

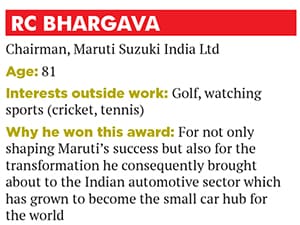

RC Bhargava joined what was then an auto PSU as its third employee. Today, the 81-year-old is chairman of Maruti Suzuki, India's largest auto company, and Japanese major Suzuki's biggest subsidiary. T

Award: Lifetime Achievement

Osamu Suzuki doesn’t squander much. Neither money, nor words. The fiscal prudence and cost-effectiveness he exercises in business extends to his communication style: The chairman of the $25 billion Suzuki Motor Corporation (SMC) speaks softly and in a measured manner—be it to praise a job well done or to point out a shortcoming.

But there is a departure. Ask him about RC Bhargava, 81, chairman of Maruti Suzuki, and his words reflect a certain animation. “Without RC Bhargava, Suzuki Motor Corporation would not have succeeded in India as [it has] today,” he tells Forbes India in an email from Hamamatsu, Japan, where SMC is headquartered. “I believe that an encounter with such a man of fairness, purity and the ability of making right decisions… was key [for Maruti’s success].”

The ‘encounter’ he refers to took place in March 1982 when the Indian government was desperately looking for a joint venture partner for its ‘people’s car’ project, originally envisaged by the elder son of then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, Sanjay, who had died in a plane crash in 1980. Many global players had shied away from the opportunity, which was not unexpected as India was then a socialist economy and government involvement in making a car, considered a luxury product at the time, was not an inviting prospect. Also, the country was technologically, in terms of the cars manufactured then, backward and the ecosystem to produce a modern car did not exist.

The PM, however, wanted the first car to roll out of Maruti Udyog Ltd by December 1983. So when SMC evinced interest, V Krishnamurthy (handpicked by Indira Gandhi after the successful transformation he brought about at state-owned engineering firm Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited or BHEL), who was Maruti’s vice chairman and managing director, and Bhargava, its director (marketing & sales), rushed to Tokyo for a meeting with Osamu Suzuki.Suzuki, to everyone’s surprise, agreed to partner with the Indian government after just a few rounds of discussions. No due diligence was done, either on India’s auto sector or on government policy. This, despite the fact that Suzuki’s team in Japan was still not convinced about the project.

When asked by his employees about the speed of his decision, Suzuki replied that he believed it was the people who determined how any project performed and everything else was secondary. And from the first time he met Krishnamurthy and Bhargava, he knew SMC could do business with them. “Since then [1982], our friendship [his and Bhargava’s] and trust has continued for more than 30 years,” says Suzuki.

The deal was inked on April 1982, and SMC took a 40 percent stake in the PSU. Since then, Maruti Suzuki (now majority-owned by SMC) has grown to become intrinsically linked to the future of the Japanese car major—consider that India is the fastest growing market for Suzuki. In FY15, Maruti Suzuki posted revenues of Rs 48,606 crore, sales volumes of 12.92 lakh units and a profit of Rs 3,711 crore. It is today SMC’s largest subsidiary and has a 47 percent market share in India’s passenger car market (as of August 2015). Hyundai is next with a little over 20 percent.

It wasn’t a smooth ride, though. There were many roadblocks along the way: A complete breakdown of the relationship between the government of India and SMC, the entry of global car majors into the country post-liberalisation as well as periodic labour strifes, to name a few. Bhargava, who has been with Maruti for around a quarter of a century now, had to tackle all these issues while ensuring that the company did not adopt a PSU mentality—it was, after all, majority-owned by the government for over a decade between 1981 and 1992. He also had to maintain the fragile relationship between the joint venture partners and manufacture modern cars in the most cost-efficient manner possible.

In ascertaining the company’s success, Bhargava was also painting a bigger picture, that of a strong automotive sector in India. Maruti’s success came from its ability to keep costs down and for that, Bhargava had to work closely with the Indian auto component sector to improve its quality to a level acceptable by SMC. Modern technology was adopted, new manufacturing practices were imbibed and the auto-component ecosystem developed.

The last one proved to be the most challenging as not a single component of the car that SMC wanted to make in India was available locally. “It took us a lot of effort and the entrepreneurs in the auto component sector had to unlearn and learn what they had to do,” says Bhargava. “They were not exposed to modern technology and manufacturing practices that were in vogue globally.” Executives from Maruti worked closely with suppliers to make this possible. “[Till then], automobile manufacturers treated component makers as people necessary to the system but not necessarily contributing to it. Component makers were not treated with respect and were not expected to question any decision or practice of the vehicle manufacturer,” Bharat Forge CMD Baba Kalyani is quoted as saying in Bhargava’s book The Maruti Story.

As Maruti slowly increased the local content in its car, India’s auto component sector modernised. In the process, the automotive industry, as a whole, moved away from the days of outdated technology used in Ambassador and Premier Padmini cars in the mid-1980s.

Cut to today, and India is considered the small car hub for the world with exports reaching over 100 countries. Cars apart, most multinational automotive majors now procure a large quantity of low cost, good quality components for their global use from India. From almost nothing, auto component exports are expected to touch $12 billion in 2015-16, according to a joint report by the Automotive Component Manufacturers Association and McKinsey & Company the same report says auto component exports will touch $40 billion by 2020.

“The development of the auto industry in India gives me a great degree of satisfaction,” says Bhargava. That, he says unequivocally, is the single-most important contribution he has made in his career. And he has his share to choose from, given his years in bureaucracy and, later, the corporate boardrooms of India Inc.

WELL BEGUN

It wouldn’t be inaccurate to trace the beginning to, in this case, the very beginning. The youngest of five brothers, Bhargava was the beneficiary of a good education, thanks to his father, a paper technologist who headed the pulp and paper wing of the Forest Research Institute in Dehradun, who sent his sons to Doon School. “He did not buy any land or house, but invested almost his entire government salary and savings in educating us,” says Bhargava. This stood him in good stead as he entered Allahabad University in 1950 for a bachelor’s degree in science he topped the university. 1. RC Bhargava played a crucial role in helping roll out the Maruti 800. Dubbed as the people’s car, the first ever Maruti 800 was delivered in 1983. 2. Bhargava with then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi at the Maruti plant in Gurgaon in 1983 3. The Maruti Gypsy was first manufactured in 1985

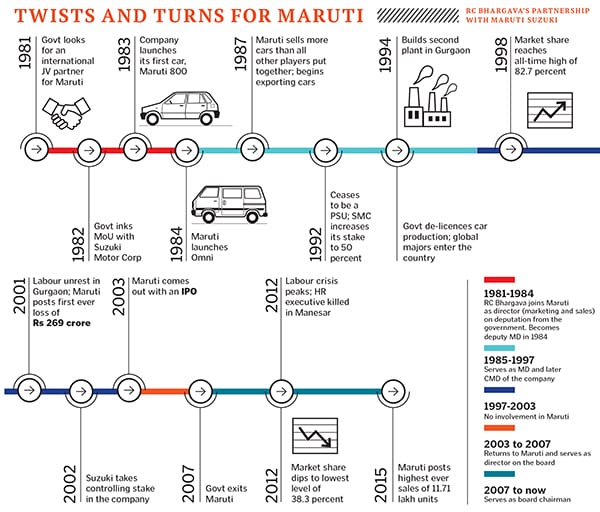

1. RC Bhargava played a crucial role in helping roll out the Maruti 800. Dubbed as the people’s car, the first ever Maruti 800 was delivered in 1983. 2. Bhargava with then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi at the Maruti plant in Gurgaon in 1983 3. The Maruti Gypsy was first manufactured in 1985

“He was an all-rounder who was not only good in studies but also excelled in sports [Bhargava played squash, table tennis and cricket—he was a fast bowler],” says Naresh Chandra, his classmate who later went on to become cabinet secretary (1990-92) and then ambassador to the US (1996-2000). “I relied heavily on his notes to pass the exams,” recalls Chandra, who even shifted his post-graduate degree major to maths (from physics) to be with Bhargava and benefit from his notes.

The next step was inevitably the Indian Administrative Services (IAS) examinations. “Those days, there were not many job opportunities in Allahabad and competitive exams were the only option,” says Bhargava, who topped his batch and, along with Chandra, joined the IAS in May 1956. As a bureaucrat in the Uttar Pradesh cadre, he worked in various state departments and undertook central government deputation as well. He left his mark with every responsibility he held, says Chandra, who was in the Rajasthan cadre, but their paths crossed quite often.

A couple of decades later, Bhargava—on a deputation to the central government (1974-77)—became the joint secretary in the ministry of water and power headed by KC Pant. There, he approved the country’s first pithead super thermal power station and was also responsible for setting up NTPC he was its first founder director. He, in fact, started the process of separating generation and transmission in the power sector (the unbundling improves efficiency as each job is considered a profit centre). “The tragedy of this country is that this process is still happening decades later,” rues Bhargava.

Krishnamurthy, who was in the midst of transforming BHEL at that time, was impressed by Bhargava’s work and asked him to join his company on a deputation, but Pant refused to let him go.

Later, when Emergency ended in 1977 and the Janata Party government came to power, Bhargava was posted to the cabinet secretariat (1977-78). Here, he had a ringside view of the decision-making in the upper echelons of the government as he would attend the meetings of the cabinet and the group of ministers. “The decision-making was slow and the thrust was on consensus which led to many good ideas getting dropped even if just one person opposed them. Nothing actually moved. It was too boring,” he recalls. “That is when I first began to wonder if continuing in the government was a good idea.”

It was at this point that he joined BHEL on deputation in 1979 as director (commercial). Later, when Krishnamurthy moved to Maruti, he called Bhargava to join him there too.

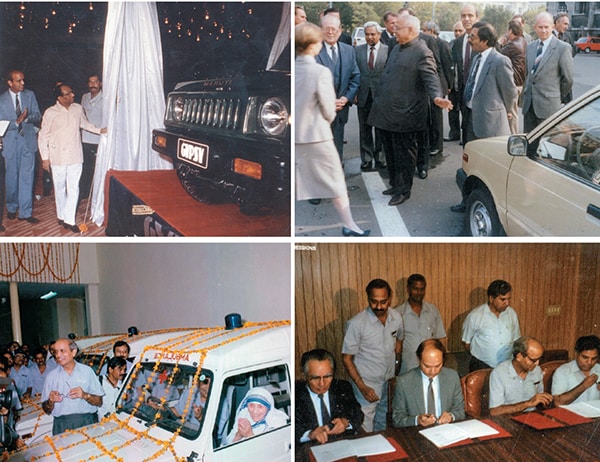

Krishnamurthy’s abiding faith in Bhargava is effortlessly explained by him. “I always found him to be out of the ordinary in the IAS,” Krishnamurthy says. “Most bureaucrats found problems in the solutions, but he was constantly looking for solutions in the problems.”(Clockwise from top left) The Maruti Gypsy was first manufactured in 1985 RC Bhargava gifts the company’s millionth car to Mother Teresa in 1985 Maruti first exported its cars in 1987, to Hungary Suzuki Motor Corporation increased its stake in Maruti Udyog Limited to 50 percent in 1992

THE MARUTI QUESTION

Bhargava joined Maruti in July 1981 on a one-year deputation, becoming the company’s third employee. This move would also help him take a critical decision—whether to remain a bureaucrat or not. Government rules did not permit him to extend his deputation. The government had made it very clear to him: Come back to civil service or retire from it and get absorbed by Maruti.

Most friends and colleagues advised him to return to his cadre. “He had a bright future in the IAS and an outstanding record to back him. He was the batch topper and definitely had the scope to become cabinet secretary,” says Chandra.

Pit the lure of a bright future in the IAS against an unknown project and a highly politicised one at that. Indira Gandhi wanted to give shape to Sanjay Gandhi’s vision of a small car. But the company did not have the technology or a partner to source it from. It neither had a factory nor employees. Its future was all but uncertain.

But Bhargava, who was 48 then, was grappling with a different set of concerns. “A government job had stopped exciting me as had the thought of becoming a cabinet secretary, having seen the person at work when posted at the cabinet secretariat,” he says. “I got an idea about what that person can do or not do.”

The other factor was financial. Civil servants then were poorly paid (his monthly salary was Rs 2,250). He wondered what he would have with him when he retired at 58. Pensions were low too. “I had no savings or assets. Like my father, I wanted to give the best education to my children,” he says. However, he found that to be difficult even after his wife Aruna, now 72, took up a job.

Also Bhargava was against becoming a liaison officer post-retirement (a role many bureaucrats take on to help companies survive the myriad laws and government procedures) to sustain an income. “It is a terrible job. Smooth talking my way in the corridors of power and pushing a businessman’s interest were not qualities I possessed. I was way too blunt for that,” he explains. Also an early realisation that the status the IAS offered was for the post and not the individual helped him bite the bullet. “A lot of people get taken up by the halo that civil services offer but that was never an attraction to me.”

But wasn’t Maruti’s uncertain future a deterrent? “I did consider that. [But] the idea was that if Maruti failed, the time I spent there could help me build a profile for another job.”

Bhargava quit the IAS in 1982 and continued with Maruti full-time as its director (marketing & sales), becoming one of the first bureaucrats to make the shift to the private sector. At Maruti, under the guidance of Krishnamurthy, he started putting things together from scratch—recruiting and training employees, setting up a factory, identifying a joint venture partner, zeroing in on the car that needs to be produced, rolling out the distribution network and creating the supplier ecosystem. “Krishnamurthy, who was considered to be the top Indian manager at the time, gave me a free hand.” And that proved invaluable to Bhargava as he stepped into the unknown. BUILDING BLOCKS

BUILDING BLOCKS

Twenty-five years on, ask Bhargava to name the single-most important reason for Maruti’s success, and he cites a cultural transformation at the heart of it. Two different worlds were colliding when Maruti and SMC came together. “When Krishnamurthy and I were in Japan, we were asking ourselves how the Japanese became leaders in manufacturing. They did not have access to raw material which would have given them a competitive advantage. Yet they manufactured and exported products that were of good quality, but were cheaper, forcing the US and Europe to impose quotas,” says Bhargava. “They could do it because of high productivity levels, the ability to do it right the first time and discipline.” It was this culture that Maruti introduced in India.

It was not adopted blindly but adapted to Indian conditions. “We had to understand what is good and how it can be used in India. There were issues that flared up constantly,” says Bhargava.

For instance, when Maruti introduced attendance incentives, people in SMC were shocked. In Japan, attendance was always high and there was no need to incentivise it. “But in India, absenteeism was high. We needed to bring the attendance level to Japanese levels and for that, some incentives were needed,” he says. It was a similar case with productivity incentives.

There was another fundamental gap in the work culture. “Workers in Japan believe that their long-term future in terms of career growth and material benefits is directly linked to the company’s performance and all management practices are consistent with strengthening this belief,” says Bhargava. But in India this crucial link between corporate performance and employee benefits did not exist. “If a company goes bust, jobs are protected. Wage hikes and bonus are fixed in a manner that has little to do with a company’s performance. Workers can go on strike but their salary is paid,” he says. “The biggest challenge was to establish that severed link.”

One of the outcomes of this effort was the employee suggestion scheme, something Bhargava is very passionate about. In the last five years (between 2010-11 and 2014-15), workers at Maruti Suzuki have offered 20.46 lakh suggestions which translated into savings of Rs 1,621.50 crore. “This is a sign of strong employee involvement,” he says. This also helped the company overcome virulent labour problems which had led to the death of an HR executive in July 2012.

A QUESTION OF TRUST

“Trust is the key to working with the Japanese and it helped us in successfully adapting their work culture at Maruti,” says Bhargava. Suzuki, for his part, has an unshakeable trust in Bhargava. This was on display when SMC decided to discontinue Maruti 800 in 1992. Maruti was shocked as its executives felt that there was still a lot of life left in the car. Bhargava took up the matter with Suzuki after all attempts to convince SMC executives failed. Suzuki heard him out and agreed (Maruti 800 continued to be the volume spinner for Maruti for another decade).

There have been many similar instances. “He believed that if I tell him something, it will be right. It is an acknowledgement that I know India better,” says Bhargava.

While this relationship helped Maruti, it also put Bhargava in a spot. When the ties between the Indian government and SMC hit a low in 1994, he was accused of being a Suzuki man trying to hurt India’s interests. “Maruti grew way beyond anyone’s expectation and was highly profitable. Instead of judging me by what I was doing, my loyalty to my country was questioned,” says Bhargava. The Central Bureau of Investigation filed cases against him and the media was full of stories against him. At one point, the government tried to remove him as the head of Maruti and filed an application with the Company Law Board on the ground that he was unfit to be a director (Suzuki would not let Bhargava go and in an unprecedented move, got himself impleaded to fight the case).

The rough times have made him more spiritual. “I always believed in god but was against performing any ritual or visiting temples, he says. While giving a lecture at a college in Puttaparthi in Andhra Pradesh, he had a chance meeting with spiritual leader Sathya Sai Baba, who told him that problems will come and go like a cloud. “True to his words all the cases were dropped without framing the charges,” he adds.

Krishnamurthy, who Bhargava never forgets to give due credit to, was chairman and managing director till 1985 and then continued as chairman till 1990. Bhargava himself was managing director from 1985 till his term ended in 1997. His involvement with Maruti, though, continued after he returned as its director in 2003, and became chairman in 2007. This was after Suzuki became the majority stakeholder post Maruti’s IPO during which the government divested 25 percent of its stake (the company had ceased to be a PSU in 1992 after SMC became an equal partner).

Though an octogenarian, Bhargava still leads an active lifestyle today. He is no more hands-on in Maruti’s operations but is still closely involved in aspects such as product development, cost reduction and employee involvement. He is also on the board of a few companies such as Grasim Industries, Dabur India and IL&FS. While he spends more time working out of his home office in Noida, he ensures he plays golf regularly. “On Sundays, I play 18 holes in Delhi. On other days, it is nine holes in Noida,” he says. The sport suits his philosophy of “do your best and don’t get attached to the result. Otherwise life will become too stressful”.

Bhargava has earned this calm. Put his journey in the context of time and place, and what he has achieved becomes even more remarkable. After all, he is one of the two managers who emerged from the Indian civil services and public sector, generally perceived as inefficient and slothful, and spearheaded Maruti for its critical first 16 years and charted its success. And, in turn, changed the Indian auto industry forever.

First Published: Oct 08, 2015, 06:54

Subscribe Now