Former banker Samit Ghosh's epiphany

A single conversation gave Samit Ghosh the courage to forsake the security of a salaried job and start Ujjivan Financial Services, a micro-lender that empowers India's semi-urban and urban poor—in par

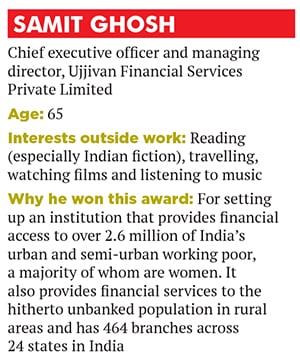

Forbes India Leadership Award: Entrepreneur With Social Impact

The year was 2004, and he had completed 30 years as a banker, having worked with some top banks including HDFC Bank, Standard Chartered Bank in Dubai and Citibank in India, Dubai and Bahrain. After the life-changing conversation, he found himself evaluating his life and the meaning of success.

But the conversation was imaginary: Ghosh’s father had passed away when he was 10 years old.

“While talking to my father, I asked him, ‘Are you happy and proud of what I have achieved in life? I’m a successful banker. I have a beautiful home. My children can study in the best schools anywhere in the world. I don’t want for anything’. He responded with a ‘So what?’ For my father, material gains did not mean very much at all,” recalls Ghosh.

What struck the former banker was how easily tangible success could be dismissed. His father was a doctor who could have built a wealthy private practice, but, instead, chose to work with government-run hospitals and serve the poor. In his lifetime, Dr Sailendra Kumar Ghosh helped set up government hospitals near the coal belt of Dhanbad in Jharkhand. He felt a moral obligation to use his knowledge to serve those in need.

It was this epiphany (and his father’s legacy) that made Ghosh decide to give back to society. He was determined to do so in a manner that would have a sustained and large-scale impact. “In India, there are about 600 million working poor. If we can give them similar financial access like what the banking industry did for the middle-class in the country, not only will it change their life for good, it will also push the economy further,” Ghosh tells Forbes India.

He was looking for a long-term fix to poverty alleviation by building a viable and scalable model to provide financial assistance to the urban and semi-urban poor who dream of becoming entrepreneurs.

His answer was Ujjivan Financial Services, which he set up in Bengaluru in November 2005 as a non-deposit taking, non-banking financial company (NBFC) operating in the microfinance space. The micro-lender lends money to working women in urban and semi-urban areas who want to set up a small-scale business. Eight years later, in 2013, Ghosh, who is CEO and managing director of Ujjivan Financial Services, registered his company under the category of non-banking financial company-microfinance institution (NBFC-MFI) with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). In 2011, the RBI had created a segment of finance companies called NBFC-MFI with a new set of regulatory framework for micro-lenders.

Over the last decade, Ujjivan has been financing loans to women entrepreneurs, who make up more than 99 percent of its total customer base of over 2.6 million. But now, the micro-lender is all set to change gears and prepare for its next big move: It is on the cusp of becoming a small finance bank (SFB). In September, the RBI awarded Ujjivan Financial Services an in-principle approval for an SFB licence. If all goes according to plan, the NBFC-MFI will have 18 months to transform into a small finance bank.

“Providing a full range of financial services to our customers has always been Ujjivan’s primary goal. This licence will help us achieve that. We can offer a whole suite of loans, savings and remittance products to the financially excluded part of our community,” says Ghosh.

According to the RBI, the objectives of setting up SFBs is to further encourage financial inclusion through the provision of savings vehicles and the supply of credit to small and micro businesses and marginalised farmers who have no access to financial services. “As a bank, we will be able to give loans and take deposits. We will be self-sufficient and not have to depend on other institutions to fund our loan book. From a regulatory and social perspective, too, we will be far more secure and not prone to the risks and insecurities usually faced by finance companies,” Ghosh adds.

Seventy-two organisations (including individuals and microfinance institutions) had applied for an SFB licence, but only 10 were successful in getting it. The other major players who have also been granted a preliminary licence for an SFB include Janalakshmi Financial Services, Suryoday Micro Finance Ltd and Equitas Holdings.

“The small finance bank licence is a step forward for Ujjivan. In the last few years, the micro-lender has become one of the most geographically diverse microfinance institutions in the country. As SFB, it will be able to offer a wide range of banking products at a much lower price point, which will also look into the overall financial inclusion mandate,” says Venky Natarajan, managing partner of venture capital firm Lok Capital, which has infused approximately Rs 50 crore in the company since its first investment in 2008.

At present, Ujjivan operates in 24 states across 464 branches. While urban and semi-urban locations remain its key focus, the micro-lender hopes to reach more people, including those in the under-banked rural areas.

“Since Ujjivan’s inception, Samit has had a clear focus of bringing financial services to the urban poor population leveraging his high-quality retail banking knowledge and principles from mainstream banking. At the time, micro-lenders were mostly catering to the rural customers,” says S Viswanatha Prasad, managing director, Caspian Impact Investment Adviser, an investment advisory firm that funds social-impact ventures.

Investors in the company point out that despite Ujjivan’s expanding loan portfolio, it has managed to maintain the quality of its operations. “The institution has an in-depth understanding of the micro-, small-, and medium-enterprise sectors. It has proven itself by significantly scaling up and remaining profitable,” says Swapnil K Neeraj, principal investment officer (financial institutions group) at International Finance Corporation (IFC), the World Bank’s private investment arm. The IFC made its first investment in Ujjivan in December 2012 and, so far, has invested about $15 million (approximately Rs 100 crore at current exchange rates) in the company.

The NBFC-MFI has come a long way since Ghosh started it with an initial capital of Rs 2.7 crore, of which Rs 60 lakh was his personal investment. As of June 2015, Ujjivan had a net worth of about Rs 770 crore. In the early years, one of its major investors was the Hyderabad-based Bellwether Microfinance Fund, which invested about Rs 70 lakh in the company. Ghosh raised the remaining capital from friends and colleagues.

Within six months of operation, Ujjivan raised its second round of funding when Texas-based non-profit organisation Michael & Susan Dell Foundation and Unitus, a non-profit that operates out of Redmond in Washington, US, and Bengaluru, and funds MFIs through venture capital investments, came on board as investors.

Both Bellwether and the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation successfully exited the company in 2012. It is rare for a social-impact organisation to not only attract investments from well-managed domestic and international funds, but also see investors exit with healthy returns. Former investors that Forbes India spoke to praised Ujjivan for the credibility it has built over the years, especially when it comes to transparency of doing business and maintaining the financial discipline of the organisation.

“None of our investors has exited with less than a 20 percent return on equity,” says Ghosh. “In the last decade, about six investors have exited partially or fully. Even my friends who had invested money in the initial days believing it to be a charity made huge returns when they exited. People who invested in the initial two rounds in 2005 and exited last year would have made about 14 times of their original capital.”

Earlier this year (between January and March), the company raised Rs 300 crore in its latest round of funding. Key new investors such as the UK’s CDC Group, Hong Kong-based NewQuest Asia Investments, private equity fund CX Partners and Bajaj Holdings and Investment Ltd participated in the round. At present, Ujjivan’s three major investors—IFC, the CDC Group and CX Partners—together hold a combined stake of approximately 40 percent in the company.

Kshama Fernandes, CEO of Chennai-based non-banking finance company IFMR Capital, feels that the ability of a microfinance institution to tap into a diversified investor base, including capital market investors, is “absolutely critical” and that’s the track record Ujjivan has achieved. “It (Ujjivan) has come across as a very strong and well-managed entity,” says Fernandes. IFMR Capital has been associated with the micro-lender since 2011 and has helped it raise debt from the capital market.

It took three years for Ujjivan to break even. Since then, it has been a profit-making NBFC-MFI despite having competitive interest rates in the sector. It charges 23 percent per annum (reducing balance) for business loans in group lending. Typically, the industry average is around 24.5 percent for similar loans. According to RBI guidelines, the margin cap for micro-lenders with a loan book of Rs 100 crore and above is 10 percent for MFIs with a less than Rs 100 crore loan book, it is 12 percent. As of June 2015, Ujjivan’s loan book stood at about Rs 3,500 crore. For FY15, it recorded a profit after tax (PAT) of Rs 75.8 crore, while its income stood at Rs 611.8 crore during the same period.

A large part of Ujjivan’s success stems from its tremendous customer focus. It is one of the few microfinance institutions to have customer relationship officers to address grievances. Ghosh himself is never too busy for his customers, whether it is to address complaints, answer questions, extend a handshake or a warm smile.

“My biggest pleasure in life is when I visit the branch offices to talk to our customers and find out what they have done with the money. Some started with a Rs 10,000 loan, and today they are taking a loan of Rs 1 lakh to expand their businesses. When I listen to their amazing stories, I feel like I have achieved my vision for the company—to help make a lasting impact on the lives of others,” says Ghosh.

The micro-lender claims to maintain one of the best customer retention rates in the country’s microfinance space at 89 percent the industry average is estimated to be about 75 percent. Over the last five years, the number of borrowers has risen at a compound annual growth rate of 21 percent. Ujjivan has a repayment rate of 99.8 percent with current net non-performing assets (NPAs) at only 0.01 percent.

Ghosh, who was born in Katrasgarh in Jharkhand’s Dhanbad district in 1949, hails from a middle-class Bengali family. His father was a doctor and mother (Padma) a teacher. “After the sudden death of my father, my mother, who till then was a homemaker, had to work to raise me. She was highly educated and had a Masters degree in psychology from Patna University. She is the one who brought me and my brother Amit (older by eight years) up. My mother was a tremendous influence on me,” says Ghosh, who studied at St Xavier’s Collegiate School, Kolkata.

He did his BA (majored in economics with mathematics) from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, in 1970. After graduation, Ghosh worked as a management trainee for two years in a company called EEDF, part of The Kuljian Corporation, an engineering consulting firm in Kolkata. He then went to study in the US, and in 1974, got an MBA degree from University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

He returned to India and joined Citibank in 1975 as a management trainee where he worked for five years, specialising in corporate banking. In 1980, he moved to Bahrain and worked with Arab Bank, one of the largest financial institutions in the Middle East. Over the years, he worked with some of the top banks in key positions. For instance, he set up and managed Citibank’s non-resident Indian (NRI) business worldwide. He also set up the personal banking business for Standard Chartered Bank in South Asia and Middle East. In 1998, he joined BankMuscat as its India CEO based in Bengaluru. In 2004, he quit to set up his microfinance company.

Now, Ujjivan is looking forward to its transformation into an SFB. The challenge lies in training and building capacity for its existing workforce (close to 8,000 employees) to sell various banking products, upgrading technology infrastructure to offer banking services and fulfilling regulatory and compliance issues in the banking industry on a daily basis. Handling higher cost of operations is also a major hurdle as the ticket size of transactions in the micro credit space is smaller.

But Ghosh is confident of a smooth transition. “The objectives and goals of an SFB are very similar to our current model. The transition for us is much easier because a lot of us in the organisation come from a banking background. The culture of efficiency and almost running it like a bank is already present in the company,” he says, adding that he will not opt for a commercial banking licence. This is unlike Bandhan Financial Services (now Bandhan Bank), one of the two NBFCs to have got a banking licence from the RBI last year.

One of his biggest hurdles is the fact that over 90 percent of Ujjivan’s share capital is currently in foreign holdings (or owned). As per the RBI norm, it should be cut down to at least 49 percent. “Most of the MFIs in the country, including us, grew on the strength of foreign venture capital and private equity funding. And unfortunately, all these do not qualify as domestic holdings. The RBI guidelines state that 51 percent of a small finance bank should be domestically owned. We have to realign our capital structure to meet the criteria,” says Sudha Suresh, chief financial officer, Ujjivan, who has been closely working with Ghosh for the last eight years.

And Ghosh has a plan to achieve that. He wants Ujjivan to be diversely owned without any single ownership. “An IPO (initial public offering) will help us achieve our vision of diversified ownership and reduce foreign holdings percentage.”

Ujjivan’s way forward lies in the expansion of Ghosh’s vision to includes not just loans, but a full range of financial services for the under-served. It is this spirit of inclusion, financial and otherwise, that truly represents the Ujjivan ethos and Ghosh’s dream. As his colleague Suresh confirms, “What’s truly inspiring is the way he carries all of us along with him in building the organisation and sharing the same vision.”

Ghosh says he couldn’t have done it without the unstinted support of his family, which gave him the courage to dream big. The father of three children—Mallika, 33, Sailen, 31, and Nihal, 28—is grateful to his late wife Elaine for her unshakeable belief in him. Hers was the voice of reason and calm amid the many moments of self-doubt that plagued Ghosh as he contemplated leaving the security of a fixed income.

But what of the other voice, the one that started him on this path? Ghosh says with quiet satisfaction: “My father would have been proud.”

First Published: Oct 12, 2015, 06:26

Subscribe Now