In 2012, an Alliance Tire field engineer noticed a growing problem on a tour of rural Europe. Industrial farmers there had been trying to move away from the traditional practice of loading harvested crops onto tractors in the field, which would then be driven out to the road and the crops transferred to the waiting trucks.

Instead, to eliminate the need for slow, expensive tractors, the farmers had started driving the trucks directly into the fields. But here was the rub: Conventional truck tyres, filled to high pressures to achieve greater speed on the highway, were damaging the soil and getting stuck in the mud.

The engineer shared this observation with Mumbai-based Yogesh Mahansaria. For the founder and CEO of Alliance Tire Group (ATG), this was an obvious opportunity. By 2013, an R&D team in ATG’s Israel plant had developed a solution, claiming to have created the world’s fastest agri-transport tyre: At twice the width and inflated to half the pressure of conventional truck tyres, the new product allowed farmers to bring the trucks directly into their fields and still reach speeds of 100 kmph on the highway. Each tyre is priced at Rs 1 lakh.

This ear-to-the-ground approach has driven innovation for Mahansaria, 39, and allowed his company to offer over 2,600 varieties of tyres. Today, ATG sells off-highway tyres such as these, used by farm tractors and heavy-duty construction vehicles, to dealers and distributors, in over 120 countries.

The company has grown at 10-15 percent per year, while the $12 billion market ticks over at 3-4 percent. The off-highway tyre business is linked to the health of heavy industries such as construction and mining. When they slow down, so does the demand for tyres, says Mahansaria. “Our international competitors are growing at two percent a year,” he says. “In 2014, almost all our European and American competitors have had negative volume growth, whereas we have had significant double digit volume growth.”

ATG’s march across the globe has been low-key, given that off-highway tyres are not the most visible products, but its success in stagnant markets such as Europe is significant. The reason for its sustained growth, Mahansaria says, is a solid need. “Nobody’s buying our tyre because he feels like it—he’s buying it because he needs to get a job done and his productivity will suffer if he doesn’t get his job done. Unlike when you’re buying tyres for your car or for your bike, which is more of an emotional purchase, this is more of a business decision—a rational decision.”

There are two myths that haunt Indian businesses: One, that they can’t scale brands globally and two, that the country isn’t ready to be a manufacturing hub. With 80 percent of his sales accounted for by the US and Europe, and a second Indian plant on the way, Mahansaria has debunked both those myths emphatically.

His journey has been an intriguing one (profiled in depth in the October 4, 2013, issue of Forbes India). This is his second swing at the agriculture, construction and forestry tyre market. After his father and he unceremoniously parted ways from the family’s off-highway tyre business, Balkrishna Industries (BKT), in 2006, private equity giant Warburg Pincus teamed up with Mahansaria for a new venture.

Together, they paid around $150 million to buy struggling Israeli tyre-maker Alliance Tire in 2007. In 2008, they set up a manufacturing plant in Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, and, in 2009, bought the US-based GPX, a tyre distribution company. Warburg Pincus cashed in on their successful partnership in 2013, when Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR) bought out its 80 percent stake for an undisclosed amount reported to be around $650 million.

The road ahead may seem smooth, but Mahansaria has navigated tough circumstances to build a global B2B business through deft acquisitions and an attention to varying market needs across continents. After eight years, his revenues, at Rs 3,450-3,600 crore for the calendar year 2014, are almost on par with BKT, which is at Rs 3,587 crore for FY14. Without a question, then, this next-gen entrepreneur’s second innings is evolving into the defining one.

There is a reassuring forthrightness about Mahansaria. He’s not the most animated speaker, yet his simple monotone conveys a depth of knowledge and self-confidence. “You walk into a room with Mahansaria and these guys who’ve been in the industry for 30 years are all listening,” says Vishal Mahadevia, co-head of Warburg Pincus India. “He’s able to command respect with a cultural connect and domain knowledge.”

![mg_77885_fila_280x210.jpg mg_77885_fila_280x210.jpg]()

The key to ATG’s success has been leveraging each country’s competitive advantages and avoiding cost overlaps. For instance, the firm doesn’t manufacture any common products in Israel and India. Also, a large procurement team in Mumbai handles the needs of both Israel (to a large extent) and India, as opposed to both plants trying to independently source material. A mid-sized company like ATG cannot afford to have multiple cost centres around the world, Mahansaria says. ATG has consolidated its sales forces too. This streamlining of processes led to profit of over $100 million for ATG in 2013.

As it stands, ATG produces high-end tyres exclusively in Israel cost arbitrage remains India’s main advantage. However, this dichotomy may well alter in the coming years. ATG and its investors, Warburg in the past and KKR today, have long been optimistic about India as a manufacturing hub. And his father, Ashok, is setting up ATG’s second Indian plant, this time in Gujarat.

“Where there is high engineering, niche, and bespoke manufacturing, India is highly competitive in the global economy because of skilled engineering and lower labour cost,” says Mahadevia. “You can’t automate the entire process. Off-highway tyre production lends itself to India’s strengths.” Unlike China, he points out, which has its core strength in low-end mass production, and is not as effective in delivering highly technical, differentiated products like off-highway tyres.

At the same time, Mahansaria is aware of the challenges to the country’s competitiveness. For one, the cost of stable power supply is unpredictable in India. This, however, has not troubled Mahansaria because infrastructure in India has improved as well as his own enterprise. “When we bought the Israel plant in 2007, the power cost there was 60 percent of India’s. Today, they’re similar at around Rs 7 per unit,” he says. “The capacity is there in India, but distribution is the problem.” To overcome this challenge, Mahansaria has appointed a senior person at his Tamil Nadu plant whose sole job is to decide whether to buy power from the local grid, Indian Energy Exchange, or third-party suppliers. “The cost of creating a unit of capacity in India is 50-60 percent of anywhere else in the world. The cost of civil work to set up a factory shed in Europe or US is 3x-4x as much as India in Southeast Asia, it is 25-30 percent higher than India because labour is more expensive,” he adds.

Mahansaria, however, is buoyed by the changes he sees, particularly with regard to the country’s port infrastructure, crucial for exporters.

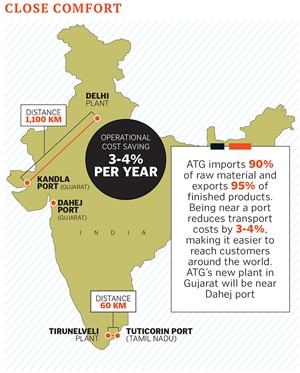

“We set up our first plant in Tirunelveli because we import 90 percent of our raw material and export 95 percent of our finished product. We wanted to be near a port,” says Mahansaria. (See infographic on p82.) Twenty years ago, while at BKT, he was limited to ports such as JNPT (Maharashtra), Kandla (Gujarat) or Chennai (Tamil Nadu) which were often bottlenecked. Now, there are options like Mundra, Hazira, Pipavav and Krishnapatnam among others. “Today, the container leaves my factory and, in four hours, it’s at Tuticorin Port in eight hours, it’s on the ship,” he points out.

Being near a port is a no-brainer for anyone who aspires to run a global business. But, at BKT, when he first pitched for a new factory in 2004, the family was wary of setting up in the South, even though it meant access to a viable port. They didn’t have the experience of operating in South India and the prospect of overcoming cultural and language barriers spooked them, says Mahansaria. They ended up building the plant near the existing one in Delhi, far from any port. The BKT board’s decision was an emotional one, rather than based on logic, he says. “It costs more to send a tyre from Tirunelveli to Delhi than it does to London!”

When he teamed up with Warburg, there was a more methodical decision-making process. The spreadsheet told the story: There was a clear 3-4 percent operating cost benefit of being close to a port. The new plant in Gujarat, too, will be near Dahej port.

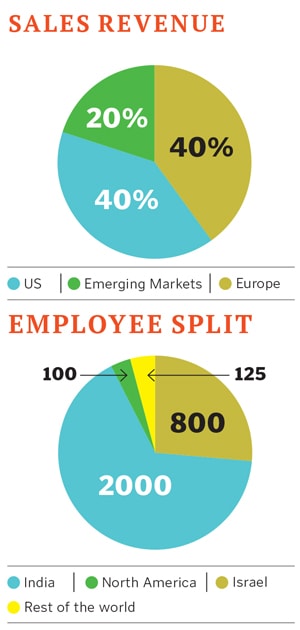

But Mahansaria will need to face his former business at some point. BKT, listed with a market capitalisation of Rs 7,600 crore, exports 54 percent of its tyres to Europe and 19 percent to the US (ATG’s sales split is 40 percent each to the US and Europe, and 20 percent to emerging markets, including India). BKT’s India sales (around 10 percent of its total mix) far outstrips ATG’s (less than 5 percent).

And, like Alliance, Balkrishna, which exports to over 130 countries, is also setting up a new facility in Gujarat. Also, BKT’s stock has more than trebled in the last year, from Rs 225 to Rs 750.

While the nascent Indian market develops, Mahansaria is keeping his eyes trained to the West. Besides market leader US-based Titan ($1.2-1.4 billion sales) and India’s BKT, Czech-based Mitas and Sweden’s Trelleborg both have off-highway tyre sales of around $800 million. And all of them are grappling with the same problem. “The health of the global economy is not robust. For a company like us, dependent on agriculture and commodities, that presents challenges,” says Mahansaria.

![mg_77887_atg_280x210.jpg mg_77887_atg_280x210.jpg]()

A threat, linked to the state of the global economy, is volatility in raw material prices. Rubber prices in India are 30 percent higher than those in global markets because of the country’s inverted duty structure. This is why ATG, despite being located just 300 km from rubber producers in Kerala, has to import all its rubber. What is more worrisome is that international rubber prices are falling to levels at which farmers no longer have the incentive to produce.

Despite this, the growth from $200 million to $600 million over the last six years has proved that Mahansaria’s model works.

Nurturing a brand of off-highway tyres involves delivering real cost-saving value to end users, while actually selling to dealers and distributors, and thus remaining a B2B, rather than B2C, business. “A lot of construction sites on which our tyres are used are very tough environments,” says Mahansaria, “so if you can engineer a product which leads to lower downtime and less punctures, that itself is value.”

Now, Mahansaria wants to grow ATG to $1 billion sales by 2018 and much of this will depend on new markets like Latin America. But since 80 percent of ATG’s sales come via replacements, how will Mahansaria know if a farmer in Argentina wants something different this time? His field office in Buenos Aires will file its weekly reports to Mumbai, like his teams all around the world.

Not surprising, then, the field engineering team is one area where Mahansaria will spare no expense. Angelo Noronha, who heads up ATG’s European business, has been with the company since 2009. He has been able to scale up the field engineering team in Europe from two to eight people at a cost of over $1 million a year. Having convinced Mahansaria, this was accomplished in just five months. Speed of execution is what sets Mahansaria apart and why the Europe business has grown almost threefold since 2009, Noronha says.

A leading European distributor of ATG’s products says, “Regularly, we have something like 10 new tyres a month to offer to our customers. This ability to enrich the product range so quickly is really unique in the market.”

Rupen Jhaveri, principal (private equity) at KKR India, has worked closely with ATG. Today, KKR is helping ATG expand into emerging markets by identifying senior talent through its global network and ramping up business with existing customers. Jhaveri says, “Most companies falter in global expansion because they try to force one way of doing things on to multiple geographies. He [Mahansaria] understands the unique challenges different regions face.” Jhaveri says Mahansaria’s execution skills are an offshoot of him being an active listener. “We found that in the EU (European Union), field engineers were more relevant,” he says. “The local business needed more of them and it was a simple decision taken by Mahansaria.”

ATG now has 12 field engineers in Europe, delivering a constant stream of feedback. They drive SUVs with trailers specially fitted with model tyres and LCD screens. Some even have kitchen extensions, so they can hold barbeques with the farmers they meet.

The agri-transport tyre is among the many products where feedback has been put into practice. “The most enjoyable part of my job is reading as many [weekly reports] as possible because sitting in an office in Mumbai, it’s very easy to get disconnected from reality,” says Mahansaria.

And, yet, he’s in Mumbai only 20 days a month. His work-life balance is not where he’d like it to be, with a typical work day starting at 10 am and ending post 9 pm. “I’m not a big believer in running a business by email. You have to pick up the phone and talk to people. I’ve found that to be the easiest and fastest way of communicating,” he says.

The more he can communicate with his senior management team over video conferences, the less he needs to be on the ground himself. “In the initial years, I was in Israel for one week in a month just to get integration underway,” he says. This year, he hasn’t been to Israel even once. And that tells a story of his management style too.

Noronha recalls how Mahansaria would initially accompany him for meetings with large-sized European customers. “Not knowing much about the tyre [business] background then, he made it a point to do a one-on-one where we went over how to react to specific situations. But today, it’s done over the phone,” says Noronha.

And that is how Mahansaria is running—and nurturing—his business: By knowing when to hold on, and when to let go. And, Noronha says, “you wouldn’t know when he’s left you and you’re running on your own. His confidence rubs off on you. You wouldn’t know when he’s not holding the bicycle anymore.”