Brijmohan Lall Munjal: A Hero for Life

Ethics, respect and relationships are the building blocks of any business, says Brijmohan Lall Munjal. And, at 90, the chairman of the Hero Group is still the force that built the world's largest two-

Award: Lifetime Achievement

Brijmohan Lall Munjal

Founder director and chairman, Hero Motocorp

Age: 90

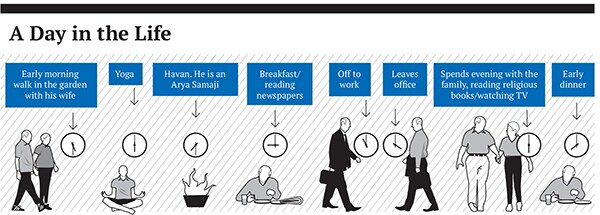

Interests outside of work: Yoga, movies

Why he won this award: For building Hero Group into the world’s largest cycle-maker and Hero Motocorp into the world’s largest two-wheeler manufacturer (by volume) and now rebuilding it after the breach with Honda

Brijmohan Lall Munjal is no stranger to adversity. For a man who found his feet in post-Independence India and, today, has a personal wealth of more than $2.2 billion, he would have faced challenges of varying hues and magnitudes. But, even for the battle-scarred nonagenarian, nothing would have compared to the events of two years ago.

Having built his life on relationships, looking upon the Hero Group as a large family of suppliers, dealers and employees working together towards a common goal, the bitter disintegration of a pivotal association would have stung.

In 1984, Munjal had joined hands with Japanese major Honda to manufacture motorcycles in a country that did not think beyond scooters. He was hesitant—he wanted to make scooters. But Honda wasn’t willing. For that, they had already found a partner in the Firodias (makers of Kinetic). But, as fate would have it, Hero Honda and its motorcycles gave everybody a run for their money and, by 2001, beat Bajaj Auto to become India’s largest two-wheeler manufacturer.

In the years between March 2000 and March 2011, Hero Honda’s (now Hero Motocorp) revenue grew from Rs 2,118 crore to Rs 20,787 crore profits increased from Rs 192 crore to Rs 1,927 crore.

“We bought Honda’s stake,” Munjal tells Forbes India at his office in Vasant Vihar, New Delhi. “They didn’t tell us that they want to leave. We told them that if they, themselves, are here to make motorcycles then they become competitors. How can a competitor and principal be the same?”

The fallout of competitiveness can be ugly, uncomfortable: Dealer poaching, negative communication and other practices that are, unfortunately, far too common. But, for Munjal, all of this was unthinkable. Trust and respect in business have always taken precedence over profits or market share.

For instance, despite the spin the world likes to give his relationship with Rahul Bajaj, chairman of the Bajaj Group, Munjal has immense respect for him.

“Bajaj started two-wheelers much before us. But not one dealer can accuse us of such practices. Rahul Bajaj and I are still friends. I have always had respect for, and from, him,” says Munjal. “I think about this a lot. Business is just business. He is running it to make a living. I am running it to make a living. Why do people start thinking that because they are competitors, they must be enemies?”

Bajaj reciprocates this sentiment, saying he has a lot of affection for Munjal because of his old-world values and ethics that are tough to find in today’s youth. “Not that I am deriding this [the present] generation but I have always called Mr Munjal a guru, not because he is older to me but because of his wisdom and common sense. Did he say that we are ‘still friends’? No question of ‘still’. We are friends. And he is the best example of a chairman in any auto company in India,” says Bajaj.

That is high praise from a worthy competitor. And it is not for nothing—Munjal’s journey at Hero is an extraordinary story of entrepreneurship in the face of adversity. Moreover, it is the tale of a man who has lived his life on the principle that if you work hard and be good to people around you, success in business will, inevitably, follow.

Munjal was born in 1923 in Kamalia, in Pakistan’s Punjab district. He doesn’t talk much about his early days, except that his parents have had the biggest influence on his life. “Both my father and mother are my idols. They also ran a business… and I learnt everything from them,” he says.

Respect for all was essential in the Munjal household, something he follows till date. For instance, he isn’t fussy about a boss and subordinate relationship. His secretary Rakesh Vashist sits just outside his room but, almost always, Munjal walks up to him to hand him a document. “It doesn’t take anything,” he says. “The time he will take to come in my room, I will sit idle, why shouldn’t I just walk up to him? And that way I can even explain something if I have to. It becomes a part of your life. And this is part of your upbringing.”

In 1944, the Munjal family moved to Amritsar in Punjab where they started manufacturing bicycle parts. It was a tough phase. “I travelled across India carrying bicycle parts in a bag. I would go to dealers to show them the samples. They would say, ‘Sir, you’ll show something and send something completely different. This won’t work’,” says Munjal.

But he wouldn’t lose heart. Over a long chat, he would convince the dealer to place just one order if it didn’t turn out to be as promised then the dealer was free to never order again. “Because we did that, our reputation, right from the first day, was very good. And then people stopped asking for samples. They would directly place the orders,” he says. But it was a gruelling time. “One day, I would be in Bangalore and the next morning in Tuticorin. And then go from Nagpur to Bombay,” he adds.

Just before Partition, the family had to move again. Their next destination was Ludhiana. It was here that the idea of manufacturing bicycles was born. Munjal says the bicycle-makers of that time, Raleigh, Hercules and Atlas, mocked him. “They said they had got the technology from England, loans from banks and then started making bicycles. They would say, ‘Will you do it just like that?’. Within six months of us starting operations, they were all taken aback,” he says.

What worked for Hero was simple—whatever was promised was delivered, and there was no attempt at profiteering.

“Other people would show something and deliver something completely different. Or after one consignment, if sales were good, they would tell the dealer that the price of raw materials had gone up and then increase the prices. We never did anything like that, unless the Government of India announced that price of raw materials had gone up,” says Munjal.

Travel, and the associated experiences, played a significant role in his life. During his bicycle manufacturing days, while in search of machines, Munjal found inspiration from Germany. “People used to be surprised at why I would go to Germany so much. But I got the best technology, met such nice people and was very impressed with their working style,” he says. “I saw that if a person committed to something, even if it is a loss-making proposition for the company, he would go out of his way to keep his commitment. And the Germans would never do an incomplete or inferior job. That influenced me… that whatever I do, I should do it perfectly.”

Those were the days of the ‘Licence Raj’. It was easy to get tempted and make money through a licence for a commodity in short supply, such as steel sheets, oil or even power. These could be traded in the market for a handsome profit. “We had a licence to buy steel sheets and if we were to just sell that, there would have been no need to make bicycles. But, with God’s grace, we never ever thought like that,” says Munjal.

Pawan Munjal, his son and managing director of Hero Motocorp, says he has been fortunate to have a front row seat to watch his father’s fascinating story unfold. “I vividly remember the early days when we were venturing into motorcycles—it was the time of the ‘Licence Raj’ and restrictive economic policies. Just watching him at work was an education in itself. Even in those days, he was a stickler for principles—with an unshakeable commitment to honesty and integrity,” he says.

These values helped Hero build a reputation where dealers and suppliers had unflinching trust in the company.

Jayant Davar, chairman of Sandhar Technologies, and a supplier for Hero Motocorp, says that while many companies claim that suppliers are part of the company, Hero has actually put this into practice. Typically, it works like this: An order system in most OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) includes sending a drawing, setting a target cost, getting a quotation, considering the best option and, eventually, placing an order.

“But I have never discussed costing with Hero. There is an implicit belief that a supplier will offer the best price so there is no need to negotiate. That is a partnership in the true sense and that is why I have never heard that Hero’s plants have stopped production because some part has not arrived,” says Davar.

In more ways than one, Davar owes his career to Munjal. “He is a godfather to me. I come from a family of professionals my father was a banker. I completed my engineering and was ready to go abroad for my MBA,” he says.

“This was around the time Hero Honda was starting out and Mr Munjal convinced me to start my own venture. Today, Hero is not the largest part of my business but I can say that I owe my existence to him,” he added.

At Hero, there are many such stories about Munjal—be it knowing the company’s thousands of dealers on a first-name basis or personally calling suppliers on their birthdays. But Munjal doesn’t find any of this surprising. “Wouldn’t you do that if it was your family?” he says.

The one thing that takes most of his time these days is solving people issues. “I don’t know how but this has become a norm in the company that whoever has a complaint or a problem, he wants to speak to the chairman,” says Munjal. His principle is simple—it never hurts to listen to everyone.

For instance, a harried dealer once called on him because, despite placing repeated orders, Hero wasn’t dispatching two-wheelers to him. “He came all the way from West Bengal and said that nobody was listening to him. I called the department concerned and enquired about it,” says Munjal.

“Immediately, my people sent him a letter detailing the issue and the reasons behind it. It was his mistake. But I pacified him and told him to first set his house in order.”

Clearly, age hasn’t worn him out or dulled his passion. Even at 90, Munjal still clocks at least six hours in office every day. Ask him why and he informs you that everybody asks him the same question. And he doesn’t see the point of it.

“When I am still on duty, what is the point of not coming to office? What will I do at home the whole day? You are being paid for this,” he points out. “What right do you have to not do a full day’s work and still draw a full salary? The biggest thing is that I enjoy working. I enjoy coming to the office and I look forward to the day.”

So no chance that he will hang up his boots anytime soon? Munjal quashes that notion immediately. “Till the time that I am capable of work, I will not think about retirement,” he says.

Nobody is complaining. Least of all his son, Pawan, who now has the task of proving that Hero is a lot more than just Hero Honda.

“Father continues to remain our guiding light as my team and I take his legacy forward with a commitment to sustained leadership, albeit in completely different circumstances,” he says, “a solo journey with aggressive plans to expand our global footprint forging new technology alliances with global partners and retaining our leadership at home in the face of intense competitive challenges.”

On Hero’s Future

“This company is going to last for a long, long time. Because it is neither in my heart nor my children’s hearts to become rich quickly. If we keep satisfying the customer, who pays money to purchase our products, there is no reason for us to fall behind. Our culture is not to overcommit and underdeliver. First, prove your capability and then talk. Not the other way around. I am very grateful to God that my kids Pawan and Sunil talk only about what they have accomplished or what they have the capability to deliver.”

First Published: Oct 21, 2013, 06:29

Subscribe Now