Anand Mahindra: The Federator

After 32 years in the Mahindra Group, and 15 months as chairman, Anand Mahindra has emerged as an all-weather entrepreneur who knows how to take the right risks and avoid the rest

Award: Entrepreneur For the Year

Anand Mahindra

Chairman and MD, Mahindra & Mahindra

Age: 58

Interests outside of work: Music, movies and photography

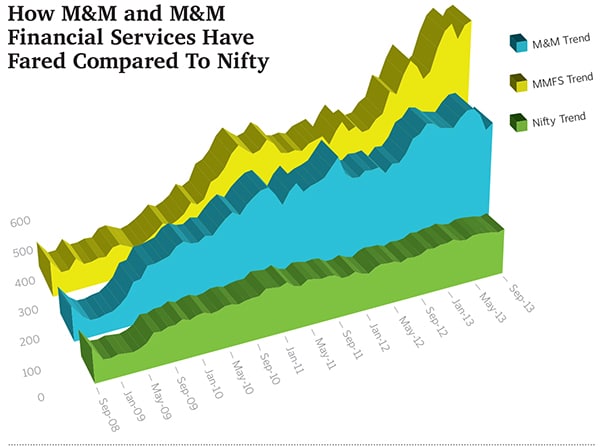

Why he won this award: For the tremendous growth seen by the Mahindra group, from a turnover of around $1.35 billion a decade ago, to $16.2 billion today. The group is now a federated structure, and not a centralised conglomerate.

He learnt weaving at school for a while, choosing it over woodwork. And it is the direction of the threads in a fabric that come to Anand Mahindra’s mind when looking for words to describe the span of his 32-year career at Mahindra & Mahindra. “To me, the peaks and troughs seem to flatten out. They seem not like highs and lows, but like the warp and weft in a weave,’’ he says. Things intervene and everything seems like it was a necessary learning, to get to where you are. Nothing seems excessive.

When Forbes India met the 58-year-old Mahindra at his new office at Gateway House, an oasis of calm in South Mumbai’s busy Apollo Bunder, he was in a reflective mood. He moved to this office over a year ago after taking over as chairman of the $16.2 billion group from his uncle Keshub.

On this day, the man, who now runs a group founded by his grandfather 68 years ago, has more things to complain about—if only for a fleeting moment. He is unhappy that someone in the ministry of finance wants to tax his sports utility vehicles at a higher rate just because they use diesel for fuel (“If I am growing, I will be taxed?” Mahindra asked the bureaucracy). He is flabbergasted that someone in the ministry of commerce and industry would free foreign direct investment in education–only to put in a clause restricting the opening to non-profit universities (“What for? Let them make money”). He bristles when we ask him whether he should be making scooters (“Why don’t you ask a well-known Japanese company why it went from two-wheelers to cars?”).

But cribbing is not what Mahindra does best. If that were so, he wouldn’t have been able to grow the group 12 times in a decade from around $1.35 billion to $16.2 billion in 2013. The group he heads now is unrecognisable from the one he joined 32 years back when he returned with an MBA from Harvard to join his father Harish Mahindra’s company, Mahindra Ugine Steel Company (Musco).

“When India opened up post-1991, one of the companies that I thought would go under was M&M,” says Vijay Govindarajan, professor of international business at Tuck School at Dartmouth. “But the remaking of this group has been dramatic. People say one man can’t make a difference. In this case, one man has. If you take him out of the equation, the story would have been different.”

In the last five years, the Mahindra group has executed 33 mergers and acquisitions worth $4.2 billion. The group has grown beyond making steel and rickety jeeps and tractors. Today Mahindra & Mahindra (M&M) makes SUVs—in India and South Korea (Ssangyong). It exports to Latin America and South East Asia. Mahindra Tractors is the world’s largest tractor company selling tractors in India, China and the US. The group also makes cars, an electric car, motorcycles, scooters, trucks, yachts and aircraft.

At Mahindra Systech, it makes auto components across five continents. Tech Mahindra is the fifth largest IT services and IT consulting company in India. Mahindra Retail (Mom & Me) sells products for expecting mothers and babies. More than 1,60,000 Indians choose to take a break with Mahindra Holidays and Clubs every year. Mahindra Agriculture is the country’s largest exporter of grapes and pomegranate. With a market capitalisation of Rs 15,000 crore, Mahindra Finance is the largest non-banking finance company in rural India. Mahindra Solar is making inroads in solar farms. Mahindra Logistics is a Rs 1,400 crore business already. Mumbai Mantra makes movies, though not very successful ones so far.

Anand Mahindra’s mantra is not about winning all the time, but to ensure that failure does not cripple. He is building a live, growing organisation—one that can evaluate, incubate, build and scale up businesses continuously, even while the flops fall by the wayside. It is tempting to see the “group” as a conglomerate, but Mahindra prefers to call it a “federation” where each company is ring-fenced from the damage failure elsewhere can do, even while being free to finance its own growth and make its own mistakes.

In theory, such a federation should be able to expand infinitely, he says. M&M, the flagship, is the major shareholder and the spine of the structure—the lever that makes things work.

Mahindra sees his role as group head as one where he—with help—assesses risk. “Measured risk-taking is at the heart of entrepreneurship,” he says.

“Whenever I have been unhappy about myself in my career, it has been because I have not taken an adequate and measured risk,” says Mahindra. It is a lesson he learnt early. In 1994, M&M was keen on setting up a castings plant because there was a huge shortage of quality metallurgical castings. With a total investment of Rs 250 crore, the company had partnered with Mondragon Corporation, a Spanish company, bought land in Baramati (near Pune in Maharashtra) and was almost ready to go. But suddenly there was a downturn in the tractors business and M&M got cold feet. “This would have been the beginning of the components sector. And we regretted it greatly when the market took off and one of our biggest supply chain constraints was quality castings. That taught me to never look at investment decisions over a short period of time,” says Mahindra.

His decisions illustrate his attitude to taking measured risk—and avoiding them when they are too hot to handle. When the bidding for Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) went too high (with the Tatas as rivals), the Mahindras opted out. It’s not that JLR was not a good buy, but the group could not afford to take that big a risk. However, the Satyam acquisition was a risk Mahindra was willing to take. Didn’t the prospect of litigation from sore investors scare him?

M&M studied the US tort scene. Chairman Emeritus Keshub Mahindra says, the group figured that American lawyers would settle for a reasonable figure, often much lower than the initial quote.

Apart from risk assessment, Mahindra sees his next challenge as defining the principles that will make the Mahindra federation of companies sustainable. Many new businesses started during his watch are unrelated to M&M’s core automobile focus, and often the group does not decide its business bets by looking at IRR (the internal rate of return). Mahindra has refocussed the group towards consumer-facing businesses. Like Apple, he wants to build businesses that can escape gravity and transcend boom-bust business cycles.

Bringing Up Satyam

The Satyam example is instructive in understanding Anand Mahindra’s approach to risk-taking and business growth.

The group’s entry in the fast-growth IT business was spearheaded by Tech Mahindra, which was focussed on telecom software.

Led by Vineet Nayyar, CP Gurnani and Sanjay Kalra, it had grown to about $800 million and by 2008 it was closing in on the coveted $1 billion turnover mark. Inorganic growth began to look appealing as the company wanted to make it to the big league. At the time, Mahindra and B Ramalinga Raju, promoter of Satyam Computers, were both on the board of the Indian School of Business (ISB). At one board meeting, Mahindra asked: Why not consider merger?

Raju didn’t take the bait. “Raju never came back to me, which I found strange. He was under strain because there was a rumour that IBM was planning to take over and his holding was down to about 12 percent. I told him: If we do a merger, it would be very interesting—solves your problem and solves our problem of growth,” he says.

Mahindra didn’t know then that a bomb was about to implode in 2009, when Raju sent a letter to the stock exchanges admitting he was cooking the books at Satyam. But he saw it as an opportunity when Satyam was on the block a year later. He needed to know two things before he started. His first question was to the then Tech Mahindra CEO Vineet Nayyar: “Are you willing to devote your life over the next few years to turning this around?” Nayyar was game. The other thing: The profits may be fictitious, but were Satyam’s people for real? Were they competent?

Mahindra did his own digging to get the answers. He made calls to Satyam’s customers all over the world. He spoke to Kevin Turner at Microsoft, Bill McDermott at SAP and to top managers at GE. They all said they were very happy with Satyam’s work and its people. It was pretty simple after that, Mahindra says. He jokes now that for days he was merely asking like Gabbar Singh in Sholay: Kitne aadmi thhe? (How many good people were there at Satyam?)

But Mahindra didn’t tell us one crucial detail: That we got from his uncle Keshub. When Anand went to Keshub Mahindra’s office to get his nod for the Satyam deal, the senior Mahindra balked. “You can’t do that!” A stickler for propriety and the power of boards, the grand old man insisted that they take it up to the M&M board for approval. “You can go for Satyam, but you and Tech Mahindra have no authority to go for it. You are owned by M&M. On a major thing like this you cannot take a view unless you go to the M&M board,” Keshub recalled when sipping tea with Forbes India in the same office that he has occupied for the past three decades.

Listening to the older Mahindra, now pushing 90, made us wonder: Who was the real master of the game, Mahindra Senior or his nephew?

We have to probably decide on both, for in 2012-13, Mahindra Satyam paid back in spades with a profit of Rs 1,164 crore on revenues of Rs 7,693 crore. To mark the return to profits, the company paid a 30 percent dividend. The turnaround is well on its way and market watchers see it joining the ranks of Tier One IT companies.

How not to bet the ranch

How not to bet the ranch

Group CFO Bharat Doshi joined Mahindras in 1973 and he has had a ringside view of the changes Mahindra has rung in. He gives us an insight into how the group has changed both in terms of what it thinks is good business and how it handles risk. The same company that once used to name its utility vehicles by numbers (CL550, CJ500, MM540) is now obsessive about branding every one of them (Scorpio, Xylo, XUV5oo). It also uses the federation structure to allow each business to grow and find its own capital without betting the whole ranch. Doshi insists on strict financial discipline for each of the parts, complete with accent on net debt coverage ratios, etc. The risks have to be defined and understood.

The best-known example of this is the decision on JLR. Mahindra says it was always a terrific asset, but a sensitivity-analysis showed that the group was not big enough to handle it if things went wrong. Tata Motors, the eventual winning bidder for JLR, had a difficult time in the first two-three years, but has been successful in turning it around. The difference was the $97 billion Tata group size. It was big enough to take it on the chin if things went awry. TCS is the Tata cash cow that backstops all risks in the group.

M&M’s annual War Rooms are where some of these crucial go-no-go decisions are discussed and decided. These are high-powered forums meant for interaction with individual companies that form the Mahindra federation. Members of the Group Executive Board (GEB) attend the Strategy War Room and the Operations War Room, held at different times of the year. Company managements present their plans and are challenged by the GEB. All major decisions have to be defended at these meetings. Among the many shot down was a plan to get into the stem cell business.

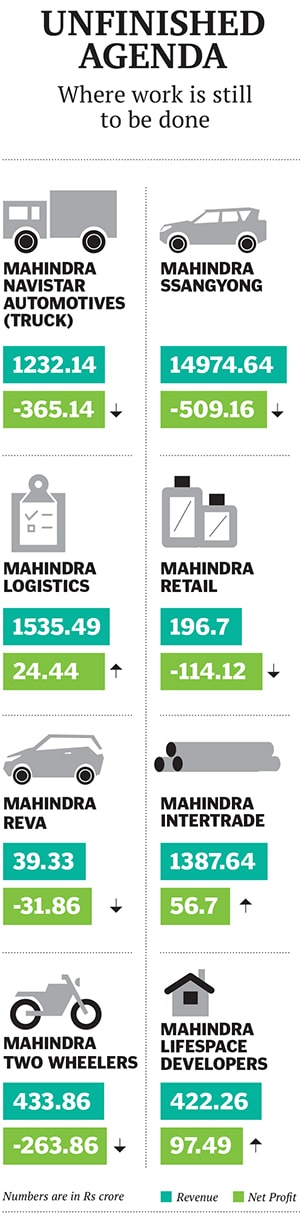

Doshi says the debate in the group is often about loss-making ventures. He cites the example of the electric car. The batteries make the car too expensive for mass use. Why do they persist with it? The automotive group that led the Reva electric car acquisition in 2010 had to justify the decision. The GEB nodded and went with the rationale that electric vehicles are a technology of the future and the company should keep a foot in this business.

Structure and Control

Anand Mahindra says the group will allocate capital to businesses it believes in. But the individual businesses are free to find partners, or, like Mahindra Finance and Mahindra Holidays, go to the public to raise money for growth. But doesn’t this dilute control? Group shareholding in some of the bigger companies is well below 51 percent, but Mahindra says it’s not about control. It is about making sure the companies are not constrained for growth. Sometimes it is about letting go.

In January this year, Anand Mahindra ceded control of Mahindra Systech to CIE Automotive of Spain. In eight years the group had built the components business to a turnover of $800 million. This was on the back of about 30 acquisitions in India and abroad. The CIE-Systech combine gave it a quantum jump in scale. M&M’s stake in the Indian company Mahindra CIE went down to 20 percent as a result of this growth. The Indian group got 13.5 percent of CIE Automotive after ceding control, but it is now the second largest shareholder in the Spanish company. Together, they are now amongst the top 25 component makers in the world. Revenues are close to $3 billion and activity is spread over five continents.

The other critical aspect of Mahindra’s management mantra is the willingness to give companies time. He is not a short termer, and there is no five-year or seven-year exit clause on businesses he invests in. “I’ve seen where patience and conviction are a [business] model. If in the seventh year of Club Mahindra we had decided to make a judgment call, we would have missed out [on its growth]. In its tenth year, it suddenly exploded and reached $1 billion in market cap at one stage. What did we invest? Rs 30 crore which turned into $1 billion,” he says.

Going by his track record on business decisions which raised quite a few eyebrows some years ago but now look like inspired calls, there’s little doubt that Mahindra had both patience and smarts. He does not throw in the towel. Some of his decisions will fail, but others will succeed.

By far the best War Room stories we heard in our interactions with the brass at Mahindras came from Hemant Luthra, president of Mahindra Systech. Luthra, an IIT Delhi grad, had built Systech to a Rs 4,000 crore venture before Mahindra ceded control to the Spanish group. A seasoned raconteur, Luthra thrives in the group’s entrepreneurial leaps.

One Mahindra Engineering Service War Room held in 2008 stands out. Luthra announced that he wanted to build an airplane in collaboration with National Aeronautics Limited (NAL), a customer for whom they did low-end engineering work. He later upped the ante, saying he would acquire an Australian aircraft-maker and a component company. As usual, he says, finance asked for the IRR numbers. Obviously, no one was doing this in India. Success depended on many variables, and customer acceptance. Luthra told the group: “The IRR may well be zero. But if this works, can you imagine what it would do to the group’s brand equity?’’  Anand Mahindra’s response is etched in his memory. After hearing the arguments, he said: “You are completely out of your mind—but go and do it!’’ He went on to acquire two Australian companies, Aerostaff and Gippsland Aeronautics, for close to Rs 175 crore. The group is now building three different planes and components. Two aircraft are being tested and will be cleared for sale next year. But, he promises, the small planes will revolutionise flying in India. They can land on any grassy strip and flying will cost only 15-20 percent more than renting a truck, he says. Farmers can carry produce out of Mahabaleshwar or Himachal and reach markets much faster.

Anand Mahindra’s response is etched in his memory. After hearing the arguments, he said: “You are completely out of your mind—but go and do it!’’ He went on to acquire two Australian companies, Aerostaff and Gippsland Aeronautics, for close to Rs 175 crore. The group is now building three different planes and components. Two aircraft are being tested and will be cleared for sale next year. But, he promises, the small planes will revolutionise flying in India. They can land on any grassy strip and flying will cost only 15-20 percent more than renting a truck, he says. Farmers can carry produce out of Mahabaleshwar or Himachal and reach markets much faster.

Incubate and hatch

Govindarajan of Tuck School believes that Mahindra’s next challenge is to take the group from $16 billion to $50 billion by 2025. “This won’t happen by itself. For that you have to aspire to be a global company. M&M has made strides but there’s a long way to go,” he says.

In 2008, Mahindra realised that there was a limit to the number of businesses he could grow. “The constraint becomes the Mahindra Annual Planning Cycle, or MAPC. That process calls for War Room reviews, which we used to do once a month and it’s now once a quarter. How many can I do? It comes down to the limits on my time and senior executive time. It’s tempting: How do you not look at new areas? I got intrigued. Then I saw how these private equity guys somehow manage these 80 companies in a portfolio,” he says. That’s how Mahindra Partners was born.

Zhooben Bhiwandiwala, managing partner at Mahindra Partners, says his outfit looks for businesses of the future. He has a more independent canvas compared to the older established businesses. Companies in the Partners’ portfolio are broadly in three categories: Those that are being incubated, like the solar and speedboat business (Odyssey), and Mahindra Namaste, that looks at vocational education. The second category has companies in the growth capital phase—ventures that need an IPO or have to find strategic partners. These include Mahindra Logistics, Intertrade, which is into steel trading, and Mahindra Retail (that has 100 stores). The last part is pure private equity activity with a clear exit in mind. The only company here is the UK-based high-end retailer, East India Company.

Each of these businesses is funded by M&M. Many of them have been tough to run.

The retail venture needed to be re-booted several times. So did logistics. But Mahindra Partners is like a quasi-PE, says Bhiwandiwala. The aim is to drive each company into a monetisation opportunity. The companies can either do an IPO, make strategic sales or, if they are good enough, move into the federation. Then Partners exits and M&M comes in. Revenues are now in the range of $750 million. “Anand Mahindra is the biggest funnel for our ideas,” says Bhiwandiwala. “He introduces us to new people and ideas on emails almost daily.”

If today Anand Mahindra seems almost like a pro in the business of taking or avoiding risks, it is because he learnt from his past trials by fire. He didn’t have an easy ride in the initial years. Back in 1981, when he joined Musco, Mahindra thought he was going to mint money in a growing economy. But the government was just beginning to get out of its control mindset and in that very year it granted 33 licences to mini steel plants. Musco, which had always been profitable, started losing money. Soon there was a labour strike.

A similar story unfolded in 1991, when Mahindra joined M&M. He tried to increase the Kandivali (Mumbai) plant’s productivity and almost got himself killed in a labour unrest that ensued. Then, when he took over from RK Pitambar as M&M’s managing director in 1997, Toyota and a whole host of multinational auto companies entered India, introducing a whole new level of competition.

Fifteen months into the chairman’s seat and things are no different. “I am no stranger to this. I am used to a crisis and I am used to people saying I am going to fail in this,” he says. “That doesn’t necessarily perversely spur me on, but I am accustomed to it and I greet it as an old friend.”

We agree. He’s been there, done that. And usually comes out on top. He’s not Forbes India’s Entrepreneur for the Year 2013 for nothing.

First Published: Oct 28, 2013, 06:52

Subscribe Now