What should be on the new government's priority list?

Incentivising investments, boosting exports and reviving consumption will be the regime's key challenges

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and members of his new Cabinet at their swearing-in ceremony on May 30 at the Presidential Palace in New Delhi

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and members of his new Cabinet at their swearing-in ceremony on May 30 at the Presidential Palace in New Delhi

Image: Adnan Abidi / Reuters[br]With the election over, the new Narendra Modi-led government has given every indication that the economy is top priority. In place as Minister of Finance is Nirmala Sitaraman, a top-performer from the previous government. Initial reports indicate a flurry of big bang reforms focusing on streamlining labour laws, creating land banks for industrial development as well as removing the cap on foreign ownership of Air India.

Also aiding growth are the structural changes the government had brought about in its previous tenure, the stabilising of the Goods and Services Tax, and recoveries from the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code that would allow banks to start lending again. In the absence of a shock like demonetisation or an external shock like the US-China trade war, there is every chance that growth will recover.

The key challenge would be getting a sustainable acceleration in growth. “We need to remember is that our economy is cyclical and I don’t think 8 to 9 percent growth is possible for long periods,” says Venugopal Garre, a director at Bernstein, a brokerage.

A look at the last five years bears this out. Real quarterly GDP growth failed to dip below 6 percent, and failed to sustain above 8 percent, for more than two quarters at a time. Growth for FY19 hit a 5-year low of 6.8 percent. Part of the reason was that while consumption and government expenditure were robust, private sector investments and exports failed to gather pace. More recently consumption has also slowed down. Accelerating growth will mean addressing each of these issues.

Investments

The seeds of India’s investment slowdown were sown in the 2004-08 growth boom. As companies rushed to expand capacity for a 9 percent GDP run rate, they over estimated demand. Sectors as diverse as housing, auto, steel and cement saw increases in capacity on leveraged balance sheets. As demand slowed after 2011, corporate India struggled to pay its interest obligations. Fresh investments by companies stopped and they spent the better part of this decade deleveraging their balance sheets.

Add to that a slowing saving rate—it has fallen every year since 2011 and is now at 30.5 percent of GDP—and there is little money left to invest. The 2018 Economic Survey warned that a prolonged savings drought doesn’t recover by itself. Even though capacity utilisation has risen to 76 percent, Indian companies show no interest in investing for the next leg of growth, and have upped dividend payouts.

“Investments are unlikely to recover without incentives,” said Mahesh Vyas, managing director of the Center for Monitoring of the Indian Economy in an interview this March. The last time in 2004, he said, the SEZ policy and the tax breaks it accorded had played a major role in reviving investments. This time the government would need to work equally hard to get corporate India to invest. During 2014-18 the only silver lining was government spending on an ambitious national roads programme. Automakers saw demand plunge in the 2018 festive season

Automakers saw demand plunge in the 2018 festive season

Image: Satish Kaushik / The India Today Group / Getty Images[br]Exports

A significant failure of the first Modi government was its inability to get India’s export engine running. A big reason for this was the fall in oil prices that led to a fall in the value of India’s number one export—refined petroleum products. But despite a depreciating currency and robust demand, India failed to capitalise on three distinct opportunities.

First, the shutdown of several specialty chemical plants in China due to environmental concerns. Most manufacturing capacity moved overseas but only a few moved to India. In aggregate business, the country gained just $1billion, with companies like Vinati Organics, Atul Limited and SRF seeing growth. Still, that paled in comparison to the potential $50 billion opportunity.

Second, the opportunity in the textile sector brought about by rising wages and labour shortages in China. While Indian manufacturers Welspun India and Indo Count did increase their business, most global textile companies chose to move production to Bangladesh and Vietnam where labour laws are more flexible. Third, the inability of Indian companies to get onto global supply chains. It remains to be seen if the recent US-China trade war gets manufacturers moving out of China to India. More recently there were minor irritants like the withdrawal of letters of credit, which resulted in the use of additional working capital for exporters.

Addressing this slowdown will be tricky for the new government. Just incentives are unlikely to get companies to invest. Take the example of Foxconn, which, despite being offered a tax holiday has still not committed to building a factory in Maharasthra. Port linkages, the ability to hire and fire, and a predictable tax regime as equally important. Consumption Slowdown

Consumption Slowdown

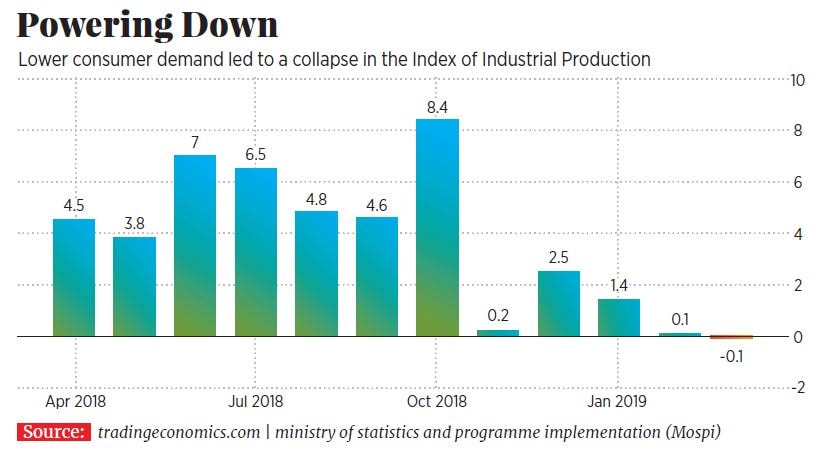

The failure to revive investments and exports led to India’s consumption engine coming unstuck in the second half of FY19. Automakers saw demand plunge in the 2018 festive season, and consumer staple companies saw volume growth slow to a trickle. (With low retail inflation price growth had been an anaemic 1 to 2 percent a year since 2014.) With consumption powering two-thirds of growth, the slowing sales of soaps, shampoos, cars and air conditioners led to a collapse in the Index of Industrial Production (see chart ‘Powering Down’).

For now the jury is out on whether the slowdown will last. RC Bhargava, chairman of Maruti Suzuki, attributes it to the elections: “We had seen this in 2009 and 2014, and I would wait till July to see if demand revives.” He’s unsure of the need for a stimulus and says he’d look closely at what the government does to spur growth. If it can get either exports or private investments take off, India’s growth would be on a far firmer footing.

First Published: Jun 03, 2019, 11:53

Subscribe Now