Trust matters the most in negotiations

To build trust, global negotiators should be aware of the role of trust or distrust in negotiations

Image: Shutterstock

Amit Nandkeolyar and his colleagues use the case of Tata Motors to provide rich insights into the varying levels of trust of negotiators and their effects on negotiation outcomes. The study suggests that trust promotes greater information sharing without the fear of exploitation, which in turn, leads to value creation and better outcomes for all negotiating parties.

Trusting others is not easy, be it in our personal or professional lives. Our ability to trust others is laced with an underlying sense of fear that in doing so, we risk being exploited or taken for granted. These concerns are more pronounced at the negotiation table where negotiating parties feel that their counterparts might be holding back information.

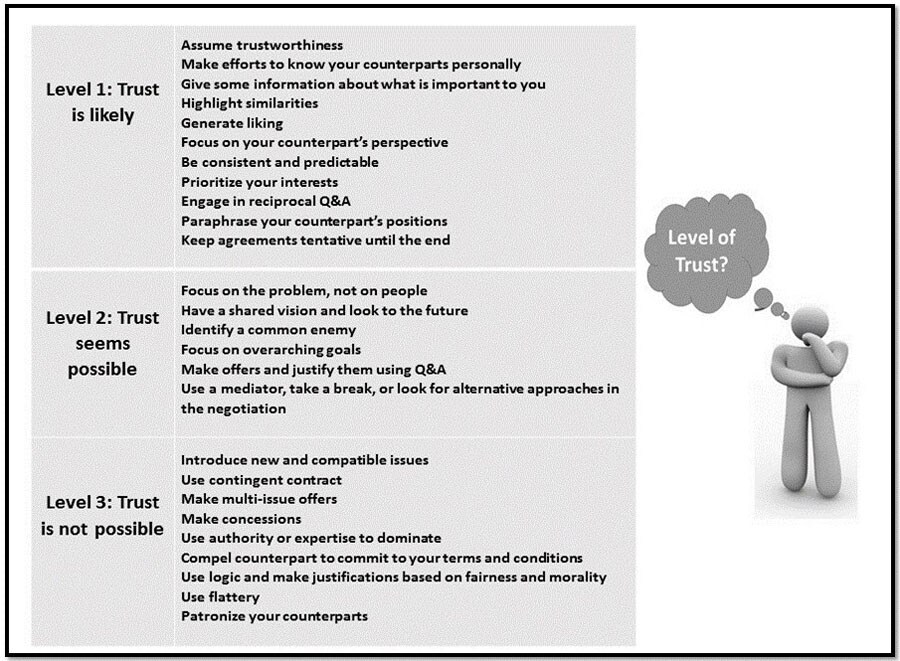

To build trust, global negotiators should be aware of the role of trust or distrust in negotiations, the existence of varying levels of trust, and the strategies they can use to identify their trust levels and adapt their behaviours to attain the best outcomes for all involved.

As Amit Nandkeolyar, Assistant Professor of Organisational Behaviour at the Indian School of Business, says “Trust is the lifeblood of negotiations. For negotiations to culminate in fruitful outcomes for all parties and for it to offer greater joint benefits to all, trust is vital. It is imperative that negotiators first understand their level of trust in the negotiation, and accordingly use strategies to ensure that the negotiation has the desired level of trust.”

Trust fosters value creation

Nandkeolyar points out that trust in negotiations leads to “value creation” for all. Value creation or ‘growing the pie’ as it is commonly called, includes behaviours that increase the resources available to claim —thereby, allowing all parties to benefit more by working together on mutual benefits.

Trust also reduces “value claiming” or efforts to take the most for oneself. The maximum joint benefits to all negotiating parties arise from negotiations that hinge on trust. Why? When parties trust each other, they are willing to be vulnerable and to share information despite knowing that the information could be used against them. This sends a strong signal that they believe in reciprocity, in other words, that the other party will treat them the same way. The combined outcomes are maximized because each negotiating party works to create greater joint outcomes, instead of claiming the greater share of value for itself. Thus, as trust replaces the fear of exploitation with the hope of reciprocity, honest information sharing takes place, reducing the chances of an impasse.

In a case analysis of the negotiation journey of Tata Nano in India, Nandkeolyar and his colleagues offer new insights on how varying levels of trust can generate rich or poor quality agreements. These managerial learnings can be used across cultures by global negotiators.

In 2008, Tata Motors was negotiating with the government of West Bengal for land and resources that would enable the production of Tata Nano, the world’s cheapest car, in addition to promoting much-needed industrialisation in the state. After two years of negotiations, Tata Motors abandoned negotiations with the state owing to a substantial trust deficit. The shortfall of trust emanated from the government of West Bengal’s actions, such as forced evacuations of farmers to free up land for Tata Motors, delays in providing housing alternatives to displaced farmers, failure to provide the farmers with adequate compensation, and a non-transparent communication policy that incensed the political opponents of the government and sparked a major resistance. Deep-seated distrust and selective, non-transparent communication between the Tata Group and government negotiators ultimately culminated in an impasse. It was apparent that the shortage of trust at the negotiating table had prevented the parties from creating value for each other.

Subsequently, Tata Motors’ negotiations with the government of another state in India, Gujarat, produced a mutually beneficial deal in which Tata Motors made an investment of Rs 20 billion (approximately US$427 million) in the state of Gujarat. Greater value was created for both the state of Gujarat and Tata Motors because their negotiation bore the unmistakable signs of being rooted in trust: information sharing, asking and answering well-intended questions about their counterpart’s priorities and interests, and genuinely working to forward each other’s interests without the intention of exploiting the other party or the fear of being exploited.

Varying levels of trust and their identifiers

The study offers managerial implications that are especially relevant for emerging economies by demonstrating differences in negotiation outcomes within the same culture. The sharp contrast of Tata group’s botched negotiation with the West Bengal government and its subsequent fruitful negotiation with the Gujarat government indicates that cultural stereotyping can be misleading and does not explain the differences in negotiation outcomes within the same culture.

Encouraging managers to look at the big picture helps avoid pitfalls such as value claiming or failure to adapt behaviours before the negotiation falls apart. For example, negotiators at Level 1 can work towards sustaining trust, while those at Level 2 or Level 3 can work on strategies that will enable them to move to Level 1. Also, based on the outcomes that negotiators are seeking, they can effectively manoeuvre their level of trust depending on what they want to accomplish in the negotiation.

Nandkeolyar says, “We hope global negotiators will use our trust indicators and construct effective strategies that lead to fruitful negotiations. Ultimately, trust matters the most in negotiations.”

Based on the research of Amit K. Nandkeolyar, Brian C. Gunia and Jeanne M. Brett.

About the Researchers:

Amit Nandkeolyar is Assistant Professor of Organisational Behaviour at the Indian School of Business, Hyderabad.

Brian Gunia is Associate Professor of Management & Organization at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School, Baltimore, Maryland.

Jeanne M. Brett is the DeWitt W. Buchanan, Jr. Distinguished Professor of Dispute Resolution and Organizations and the Director of the Dispute Resolution Research Center, Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL.

First Published: Oct 23, 2017, 07:23

Subscribe Now