Credit risk funds: Debt row

Investors should look beyond ratings while picking debt instruments

R Sivakumar of Axis Mutual Fund believes most corporate debt concerns are surrounding liquidity

Image: Aditi TailangThis is an election year, and for investors finding the right mix of capital protection and appreciation could be a tough task.

For bonds, as an asset class, Murphy’s Law seemed to have hit in 2018, with several shocks taking place. The government has missed its fiscal deficit targets for two straight financial years (for FY19 the deficit was 3.3 percent of GDP compared to the targeted 3 percent in 2019, the deficit was revised to 3.4 percent of GDP, from the earlier target of 3.3 percent) there was tightness in the money markets after the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) continued to intervene in the forex markets, and selling dollars, which reduced the rupee liquidity.

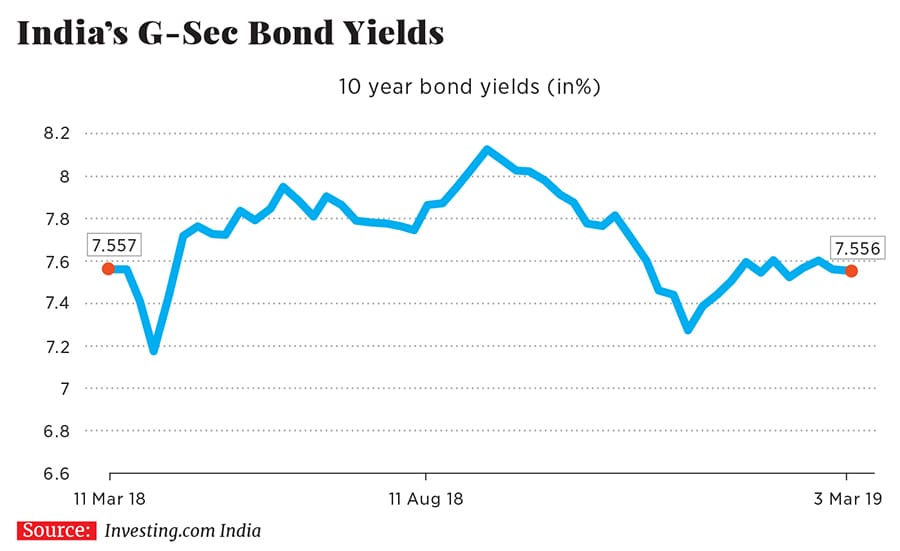

India’s benchmark 10-year government security (G-Sec) bond yields have been steady, but rose in the wake of tensions between India and Pakistan: Yields rose 28 basis points to a high of 7.62 percent on February 14 (the day of a terror attack in Pulwama), compared to 7.34 percent on December 31, 2018.

“We had had two or three rude shocks last year, from volatile oil prices to rupee volatility and the IL&FS problem,” says R Sivakumar, head of fixed income, Axis Mutual Fund. He adds that despite the buzz of several non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) showing signs of weak financial health, the only defaulter was IL&FS. “Corporate debt concerns are mainly surrounding liquidity, and whether they can fund themselves. It is not about solvency.” He adds that even as all NBFCs have substantially run down their books to reduce their outstanding payments, or make repayments in commercial papers (CPs), worries about risk are elevated but actual risks are relatively limited.

However, compared to interest rate risks, assessing credit risk will be the critical factor while investing in debt, says Feroze Azeez, deputy CEO of Anand Rathi Private Wealth Management: “We have analysed 20 Indian companies that were all rated AA+ before they defaulted. This shows that rating agencies have faltered, and hence ratings might not be seen as a good measure of credit risk.”Azeez has been using another method, z-score, to predict bankruptcy. Formulated by Edward Altman of New York University’s Stern School of Business in 1968, z-score, says Azeez, is better than ratings for determining credit risks before a company goes down. This is particularly critical for a country like India, which has 38 AAA-rated companies compared to the US that has just two. A score above 2.5 is considered good on z-score, which has five key ratios.

Besides risk, a factor that helps determine bond yields is interest rates. Considering that bond prices rise (and yields fall) when interest rates fall, investors might want to closely watch the RBI’s moves in the coming quarters. G-Sec yields have remained relatively stable despite two RBI rate hikes (in June and August 2018) and one rate cut this February. “The RBI does not have a window to cut rates too aggressively, but they will do so again,” says Sivakumar. Analysts from Nomura and HSBC suggest that a 25 percent rate cut could be announced at the next policy meeting in early April.

The RBI is in what is generally known as the flexible inflation targeting (FIT) framework for monetary policy. This means that while its focus will be on maintaining price stability—and if it is under control, which it has been (consumer price index inflation was 2.05 percent in January)—it also has an eye on growth. India’s gross domestic product for the quarter ended on December 31 stood at a 15-month low of 6.6 percent.

Sivakumar suggests investors should “play short-duration funds”. If they are buying a long-duration fund, then they should expect a softening of rates in the next two to three years. But that is not something that is obvious as of now, he adds. Some risk factors will continue in 2019, including the monsoons (which will impact farm output), the rural economy and inflation.

Feroze Azeez of Anand Rathi Private Wealth Management uses the z-score to predict bankruptcyThe case for credit risk funds

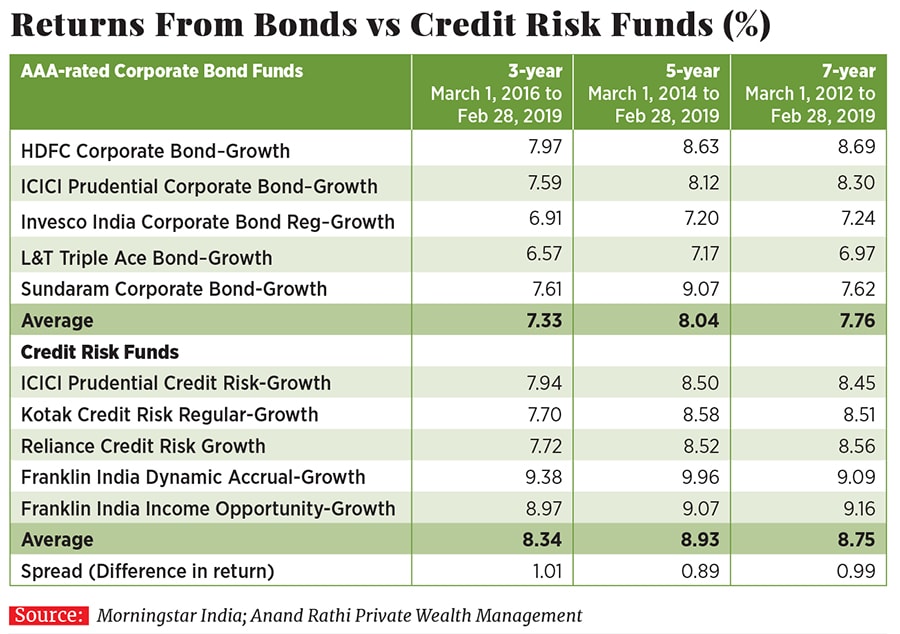

Over the past few quarters, credit risk funds have been among the most popular in India. These funds primarily invest in lower AA-rated—rather than AAA-rated—corporate bonds and CPs. Low credit rated debt instruments, being high-risk instruments, provide higher returns. The takeaway from the IL&FS crisis, however, is that fund managers need to carry out their own research and assessment before making investments, regardless of what rating agencies have provided.

In this scenario, should one buy AAA-rated bonds or credit risk funds? Sivakumar believes there are opportunities “in both parts.” It will depend on whether the fund manager is getting sufficiently higher yield to compensate for any possible credit deterioration or downgrade. Axis’s credit risk fund has a three-year CAGR of 7.37 percent for its regular plan, and 8.75 percent for its direct plan.

The fund’s portfolio includes Dewan Housing Finance Corporation Ltd (DHFL)—which has, over the past six months, faced a liquidity crunch and allegations of financial irregularities against its promoters—that is about 4.65 percent of its net asset value. Sivakumar says half of the exposure to DHFL is due in April and the rest in September. “The approach is to aggressively diversify, revisit the portfolio and even if there is pressure on credits, it will affect a small percentage of the fund.”

The past four or five years have shown that investors can, through a three or five-year maturity, earn between 10 and 13 percent more through a credit risk fund, compared to a AAA-rated bond. “Keep in mind the noise factor. Worries have been on credit over the past six months, but the actual defaults are minimal. Should you invest based on noise or evidence?” asks Sivakumar.

Speaking about the future of credit risk funds, Azeez says, “It may not have too many takers as there is limited understanding of the merits of taking credit risk, which in turn makes the category safer, as the supply of good bonds is limited.” The credit risk bond market is yet to mature in India and is expected to grow. The US bonds rated BBB and below are very prominent in the debt market, he adds.  Where to invest, then?

Where to invest, then?

So, considering new investment avenues and evolving credit and interest rates, what does the future hold?

The key is that investors should continue to stay diversified, both in asset classes and in debt products and funds. Besides credit risk funds, there are other options such as banking and public sector unit debt funds, wherein the top 10 performing funds have been offering returns of an average of 7.7 percent over one year, according to data from Value Research. These are AAA-rated investments, and an alternative to other debt products such as bank deposits.

Azeez suggests that for debt products, investors opt for the direct route and look at low-cost funds. “The returns from the best performing and the worst performing debt funds are just 2 percent,” he says. Both experts call for investors to stay away from fixed maturity plans (FMPs), where risks are higher, due to lock-in periods. While FMPs are seen as alternatives to fixed deposits (FDs), they offer indicative yields actual returns could be higher or lower than FDs, which gives an assured return.

Hence, in previous years, while investors have moved towards debt instruments with the belief that they will get relatively steady and, sometimes, assured returns, in the current scenario, they will also have to be ready to take risks that are almost similar to those in equity investments for similar returns.

First Published: Mar 19, 2019, 14:58

Subscribe Now